The EU Social Taxonomy Draft: promising buildings blocks

20-minute read

The 53-page Draft Report on “Social Taxonomy” from the Sustainable Finance Platform Subgroup recently leaked. To our great surprise, it offers an already sophisticated approach and encompasses meaningful and granular proposals. It helps grasping what an EU Social Taxonomy could look like. It differentiates on the one hand, the contribution to social objectives made through products and services sold by companies, in particular the promotion of adequate living conditions for individuals and groups in situation of vulnerability (a so-called “vertical dimension” chiefly steered by R&D, business development and marketing departments) and, on the other hand, the contribution made through processes, value chains and conducts to the respect of human rights and stakeholders living conditions (an “horizontal dimension” more likely addressed in the CSR team, human resources and purchasing departments). A stakeholder-centric approach is suggested to reflect both the positive and negative impacts companies have on workers, customers, and communities. The Report interestingly proposes to use the concept of availability, accessibility, acceptance, and quality (AAAQ). Availability and accessibility would be used for defining Substantial Contribution (SC) and “acceptability and quality” for “Do no Significant Harm” (DNSH). For the time being, social and governance factors are only a component (rather than a principal focus) of the EU Taxonomy of Sustainable Activities. We welcome these preliminary but galvanizing developments.

We, at Natixis Green & Sustainable Hub, firmly intend to nurture our capacities and presence in the social finance realm. Apart from the structuration of Social Bonds (e.g. Unédic, CADES, Icade Santé, Action Logement), we contribute to the development of social finance-related content, methodologies and tools for capital markets. In a recent article, we dug into the topic of fair transition (“A growing momentum for Fair Transition Finance”, April 2021). We also published a benchmark of Social Bonds Impact Reporting practices “The Art of Social Bonds Impact Reporting”). We moderated a Panel on the topic during the Environmental Finance ESG event on June 16 (details here).

Introducing a proper social dimension in the EU’s Sustainable Finance Regulations presents great advantages, especially in terms of contributing to adequate living conditions. We herein present our analysis of the overarching conceptual aspects of the EU Social Taxonomy envisioned by the Sustainable Finance Platform.

Main highlights:

- The document strives to be as symmetrical as possible with the Environmental Taxonomy’s architecture and functioning, precisely by replicating the “Substantial Contribution” (SC) and “Do No Significant Harm” (DNSH) mechanisms in order to avoid companies being overburdened by having to consider two completely different systems.

- It identifies various articulation options between the social and the environmental taxonomies (how should they relate to each other and coexist), including potential overlaps and risks of arbitrages between the two taxonomies (depending on the mix of SC, DNSH and minimum safeguards scope, this is the most abstruse part of the Report).

- It assesses the relevance of identifying economic activities that significantly harm social objectives (“significant harm social taxonomy”), as well as the need for minimum environmental safeguards.

- It covers social objectives related to “employee, health, human rights, equality and non-discrimination matters”, as well as social objectives linked to business ethics, governance, anti-bribery or tax compliance matters.

- It explores the ways of demonstrating alignment with DNSH (based only on compliance with the regulations or not).

More systematism in the reasoning and presentation of information will be necessary in the final draft of the Report. It is sometimes hard to navigate through the various options presented. There are numerous methodological and practical questions that will need an answer (a mix of solutions is often suggested), for instance, whether technical screening criteria must be:

- Entity-level or activity level-specific;

- Sector-agnostic (in addition to the question of the scope of sectors covered, whether only activities that can be defined as social in nature should be included);

- Inspired by the generic Do No Significant Harm (DNSH) criteria model used for climate change adaptation

- Context-based (reflecting geographic and/or cultural differences);

- Binary or with shades/different levels;

- Based on closed questions (i.e. only two possible responses: Yes or No);

- Be qualitative and/or quantitative (using performance standards and metrics that are relatively scarce, or labels);

- Related to the inherent or intrinsic contribution of some economic activities (broad contribution through the impacts arising from employment creation, pay, productivity growth and investment in HR/employees) or only to “additional benefits” (e.g.: promoting the hiring of local people, as well as use of local content and services in impoverished areas);

- Based on process, goals and disclosure (i.e. the investor or financial actor would be poised to verify that the company has set up the required process) or demonstrated through empirical evidence and data;

- Set above national and legal requirements (requiring extra legem efforts or practices, taking additional steps).

***

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Reminder on the Platform’s Organization

- The mandate of the Working Group on Social Taxonomy

- Reminder on the existing social dimension of the EU Environmental Taxonomy

- Burden of proof for DNSH and social minimum safeguards

- The context of Social Taxonomy endeavor: a heated social situation worldwide

- The need for investment in a “Just transition”

- The proposed objectives of a Social Taxonomy

- What an EU Social Taxonomy will not be

- The audience: Whom is the Social Taxonomy for?

- Highlighted differences between environmental and social matters

- Relevance and acceptability of “significant harm social taxonomy”

- Guidance for selection criteria and indicators

- The two-fold dimensions of the Social Taxonomy

- Social factors are hardly quantifiable and influenced by context

- Use of the SDG and 2030 Agenda

- Taking into account the broad contribution of businesses?

- Areas for improvement or clarification

- Calendar

Reminder on the Platform’s Organization

The Sustainable Finance Platform is an advisory body subject to the Commission’s horizontal rules for expert groups. Its main purpose is to advise the European Commission on several tasks and topics related to further developing the EU Taxonomy and support the Commission in the technical preparation of Delegated Acts.

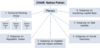

The Platform has, in principle, an unlimited duration, taking into account the different tasks provided for in the Taxonomy Regulation, and the need to amend the technical screening criteria of the EU taxonomy over time, to reflect, for instance, changing EU environmental legislation or technological developments. It has different Subgroups, notably on data usability, negative and low impact activities or on Social Taxonomy (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Organigram of the EU Permanent Sustainable Finance Platform

The mandate of the Working Group on Social Taxonomy

The European Commission gave the Platform for Sustainable Finance the mandate to work on extension of the Taxonomy to social objectives and established a subgroup dedicated to this task (thereafter called the “Working Group”). The Working Group has been tasked to publish a Report describing the provisions that would be required to extend the scope of this Regulation beyond environmentally sustainable economic activities to cover other sustainability objectives, such as social objectives.

As mentioned above, the Working Group was also asked to advise the European Commission on the functioning of Article 18 (minimum social safeguards), which requires the respect of international labour standards and human rights by companies carrying out environmentally sustainable economic activities.

Reminder on the existing social dimension of the EU Environmental Taxonomy

As of now, in the context of the Environmental Taxonomy, to be deemed environmentally sustainable, beyond complying with technical screening criteria (TSC) defining substantial contribution (Article 9) and not significantly harming any other environmental objective (Article 17), an economic activity must be carried out in compliance with social minimum safeguards.

Article 18 defines these social minimum safeguards as “procedures” that must be implemented by the entity performing an economic activity under consideration, and which must comply with the following international instruments:

- The International Bill of Human Rights (the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the UN Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights)

- The ILO Declaration on Fundamental Rights and Principles at Work

- The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights

- The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises

The implementation of these requirements has repeatedly been identified as one of the key uncertainties in demonstrating taxonomy alignment. The Report states that “experience shared by financial market participants highlight challenges in applying the safeguards requirement, including due to data gaps and raises questions about when and how compliance with article 18 can simply be assumed due to legal compliance”.

Burden of proof for DNSH and social minimum safeguards

The question on how to demonstrate the absence of violation/breach is not answered unequivocally. The Report states that the “implementation of human rights in businesses is considered to be a process which follows established guidelines and is goal-oriented, rather than based on highlighting violations which could be arbitrary”.

We are not satisfied with this statement, especially the first part. We share the view that there are many shortcomings in relying on allegation or controversy checks to demonstrate compliance with the social safeguards. The Draft Report warns about the limits of taxonomy services providers’ approaches, including allegations check. An example about ISS ESG is provided. During a webinar in February 2020, the SPO provider has Reportedly explained assessing compliance with the minimum safeguards as follows: “It must be verified that the company has not been subject to (allegations of) failing to meet minimum social safeguards in their operations”. Allegations, rumors or controversies, or their absence, are insufficient to demonstrate alignment with minimum safeguards.

However, compliance with minimum social safeguards cannot simply be deducted from presumed compliance to law. The Working Group calls in favor of disclosure about goal-oriented processes. It argues that “it should not be enough for companies to confirm that they follow the procedures of international guidelines, it should also be obvious how this is done and also be integrated on a forward-looking basis as opposed to retrospectively ticking a box in annual Reports”.

We dismiss the idea that the implementation of human rights in businesses is only a process following established guidelines and being goal-oriented. Facts and actual violations matter. It cannot be a mere “obligations of means”, best efforts and disclosure. That being said, individual cases of violations can always occur despite a proper governance. Ruling by Courts on alleged violations might be the best proxy, but justice proceedings often span over years. And in some locations, access to justice is hindered. Therefore, a mix of rulings by Courts with some criticality thresholds (defined based on the number of actual condemnations and lawsuits, gravity and significance of the abuses, but there would be some subjectivity in setting such thresholds) and unscheduled inspections and audits on a regular basis could help strike a good presumption of respect. In any case, this is challenging, and cannot become too burdensome for companies.

The context of Social Taxonomy endeavor: a heated social situation worldwide

The Working Group assesses the merits of extending the Taxonomy to social objectives. In addition to the lack of funding for social needs aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Draft Report states: “There is a widely recognised imperative, not only in the EU, for improved conditions, dialogue and diversity in the workplace”. The momentum around social topics and the need for a classification of activities is also reflected in investor’s initiatives on human rights [1] and living wages [2]. Meanwhile, the Subgroup pinpoints accidents like the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh, scandals like appalling working conditions among fruit and vegetable pickers in the EU and in European slaughterhouses.

From an economic standpoint, the Report highlights that there is a raising evidence that a growing gap between rich and poor could impede growth, trigger political and social instability, which, in turn, may deter investment. Social divisions fueled by inequality may also make it harder for governments to successfully undertake reforms and transformations such as the transition to a low-carbon economy.

The need for investment in a “Just transition”

The Draft Report reminds us that the transition to a green, climate friendly economy involves crucial changes in sectors like mining, manufacturing, agriculture and forestry with impacts on workers and communities. Furthermore, it implies the use of land for hydro, wind and solar power plants that might lead to conflicts over land use, especially in developing countries.

There is a necessity to avoid a situation whereby the burden of these unavoidable changes is unilaterally imposed on workers and disadvantaged communities. The expression “Just Transition” referring to this imperative has been popularized. The Report explains that the “Just Transition” can be understood as a conceptual framework in which the complexities of the transition towards a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy is captured, highlighting public policy needs, and aiming to maximize benefits and minimize hardships for workers and communities in this transformation.

The proposed objectives of a Social Taxonomy

According to the Draft Report, the stated goal of a Social Taxonomy is the following:

“Financial market participants […] will have a guidance on how social investments are defined and which criteria they have to apply if they want to create or invest in a financial product with social objectives or characteristics”.

The purpose is to establish a comprehensible and generally recognised way of defining what a socially sustainable activity or company is. A social taxonomy has the potential to bring alignment on how social aspects are measured. The application of these criteria by companies or by investors is poised to be voluntary.

A social taxonomy would therefore contribute:

- to direct capital flows to entities and activities that operate with respect for human rights and good corporate governance;

- to support capital flows to investments that improve the living conditions especially for the disadvantaged.

What an EU Social Taxonomy will not be

The Draft Report makes it clear that a Social Taxonomy will not be a law that regulates certain business-related social aspects like pension schemes or minimum wages. Like the environmental objectives, social objectives are to serve as an orientation for investors who want to promote sustainable characteristics or want to pursue sustainable objectives. It is a classification and disclosure mechanism.

The Draft Report says, “the taxonomy does not need to include so called “hard” corporate governance factors such as, for example, cumulative voting, dual-class share structure, majority voting, poison pills, shareowner rights”. It is a politically pragmatic statement to forge any consensus in the months to come.

The Report highlights that setting technical screening criteria in relation to communities and end-consumers is fraught with risks because not all business entities let alone economic activities have a direct impact on them. It warns that, in this context, “it will be important to ensure that criteria for substantial contribution, do not promote philanthropy or a return to early versions of CSR, in which companies engage in ‘do good’ activities that have little connection to their operational footprint or the negative impacts associated with their business model”.

The audience: Whom is the Social Taxonomy for?

The Draft Report states “traditional ways to finance social welfare, like government spending and stable systems of social security will remain fundamental”.

Nevertheless, it highlights that “private investments might play a role as well”, namely:

- The prevention of social harm by investors insisting that companies implement systems that guarantee respect for human rights.

- The improvement of the provision of basic goods and services especially to people and groups in situations of vulnerability.

We welcome these efforts to include private actors as social issues have been predominantly tackled/incorporated by public entities. For instance, in the Social Bond Market, companies are largely absent (with a few exceptions like Danone, or EDF lately). A part of the market share is made of financial institutions’ Social Bond issuances (mostly banks, through Use-of-Proceeds being loans to SMEs in distress/deprived areas, see BPCE, Caixabank, ICO). However, the sheer weight of the market is by far dominated by public agencies (Unédic, CADES, the European Union). Such orders of magnitude are normal considering the social protection mechanisms they finance, which are universal and have been massively activated by the Covid-19 crisis.

Highlighted differences between environmental and social matters

The Report rightly points out that “most economic activities harm the environment”. Even a substantial contribution, for instance to climate mitigation is defined as a threshold under which emissions must lay (i.e. it defines a maximum burden on the environment). The only exception may be biodiversity where significant contribution may consist in improving a previously impaired ecosystem. An Environmental Taxonomy therefore focuses on minimizing this harm.

By contrast, in the social sphere this is different. There are many economic activities that can have a beneficial impact on society, especially on target populations (providing employment, houses, healthcare or supplying clean drinking water, etc.).

Relevance and acceptability of “significant harm social taxonomy”

The Working Group assesses the relevance and feasibility of identifying economic activities that significantly harm social sustainability (“significant harm social taxonomy”). To mitigate the risks of unintended consequences or taxonomy loopholes, it puts forward the idea of exclusion criteria aiming at ensuring that harmful sectors or activities, such as weapons, gambling and tobacco cannot qualify as socially sustainable, despite e.g. good worker-related performance. The question of weaponry is politically sensitive as proven by the tortuous statement “the relationship between certain products like weapons of all kinds and violent confrontation is complex”.

Guidance for selection criteria and indicators

The Report suggests using the concept of availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality (AAAQ) as starting point for developing technical screening criteria. This concept is Reportedly already employed as a tool to implement rights included in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). It has already been used for water, healthcare and education topics.

|

Criteria |

Definition |

Significant Contribution (SC) or Do No significant Harm (DNSH) |

|

Availability |

A certain good or service is available in sufficient quantity and is functioning.

|

SC |

|

Accessibility |

A product or service is economically and physically accessible without any discrimination and that the related information is accessible as well.

|

SC |

|

Acceptability |

A product or service is culturally acceptable respecting the sensitivity of marginalized groups.

|

DNSH |

|

Quality |

A product or service is safe and that it meets internationally recognised quality standards which are scientifically approved. |

DNSH |

The Report suggests the following seven criteria for social taxonomy indicators:

- Indicator should be related to a norm, process or goal in an internationally recognized standard, like the UN guiding principles, the SDGs or the EU pillar of social rights.

- The Indicator must be a good proxy for the objective it addresses (e.g.: The proportion of women on board is a proxy for board diversity but not for non-discrimination in a company).

- Indicator should be concrete enough to relate it to an economic activity or to a company.

- Indicator must have a clear direction (e.g.: how to measure a good complaint mechanism? Is it good because there are many complaints which shows that workers trust it or is it good if there are few complaints?)

- Indicators should be on the same level of granularity

- Indicators should avoid driving perverse incentives or unintended consequences

- Data should be available at reasonable costs. Differences between larger and smaller companies should be considered.

Quantifiable metrics exist within the ILO Decent Work Agenda including around safe and healthy working conditions, anti-discrimination,freedom of association and employment generation and internationally agreed thresholds can in certain areas be derived for instance from ILO standards. Assessing SC criteria require to have closed questions.

We have identified interesting aspects or criteria suggested by the Working Group that should however be refined, possibly with the introduction of agreed definitions, thresholds (expressed in monetary amounts, in %, with durations specified, for instance expressed in number of months, using benchmarks) and/or guidance about assessment modalities.

- Decent employment and fair pay with low reliance on outsourcing and agency workers, paying of a living wage to all workers;

- Pay gap between executives and the median worker not excessive (ratios);

- Protection of workers personal data;

- Low use of subcontracting and temporary workers (%);

- Prohibiting abuse of atypical contracts and any probation period should be of reasonable duration;

- Equal access to special leaves of absence in their caring responsibility for women and men;

- Reasonable period of notice and right to be informed of the reasons prior to any dismissal;

- Right to timely access to affordable, preventive and curative heath care of good quality;

- Right for training and life-long learning for all employees;

- Pension and childcare arrangements funded in part by the employer;

- Comprehensive tax reporting, which enables an organization to understand and communicate its management approach in relation to tax, and to Report its revenue, tax, and business activities on a country-by-country basis;

- Establishing swift, effective and transparent recall procedures, in case their products present defects that put safety of their users at risk;

- Offering expanded guarantee periods for product defects;

- Designing their products for them to be durable and repairable (availability of spare parts, interoperability with spare parts of competitors…) and offering services that allow for a smooth multimodality experience (e.g. in transport).

The two-fold dimensions of the Social Taxonomy

The Report suggests an approach that differentiates a horizontal dimension from a vertical dimension. Such a two-fold structure is relevant has been inspired by different existing standards (such as GRI approach to implementing the SDGs in companies [3] or the Global Compact), and the “Proposal for a Social Taxonomy for Sustainable Investment” Report published in 2020 [4]. One of its authors, Antje Schneeweiß (Südwind Institute) proposes to identify two types of sectors for a Social Taxonomy: High-Risk Social Sectors & High-Contributing Social Sectors.

This two-fold dimension echoes the distinction we made between “inward” and “outward” contribution of businesses to the SDGs in our 2018 Report “Solving Sustainable Development Goals Rubik Cube”. Inward refers to the internal sphere of the organization and its impact through its own operations (upstream, wage policy, sourcing, etc.). Outward hints to the impact of the products and services sold by a company (external/outbound focused).

To illustrate this distinction, the example of the car-maker Tesla can be given (it is not in the Report). The company has an outstanding positive contribution on the vertical dimension as it sells only electric vehicles that are zero tailpipe emissions, but in the meantime, on the horizontal dimension, Tesla displays weaknesses, notably alleged violations of workers’ rights.

The Report systematically tries to identity topics that are relevantly assessed at economic entity versus economic activity levels. The model of the generic DNSH criteria might be used for social objectives (as it is for climate change adaptation). Some criteria could be cross-sectoral, while others must preferably be sector/activity specific, and in some situations, also location specific.

Table 1: Illustration of the horizontal and vertical dimensions across thematic

|

|

Operations and Conduct |

Products and Services |

|

Employment

|

Training, layoffs, employment of people and groups in situation of vulnerability, buying from regional suppliers to generate jobs (workers, decent employment) |

Training services to (re)integrate people into the job market |

|

Human Rights due diligence

|

Social auditing as a part of a HR process (workers, and communities) |

Social auditing as a service |

|

Safe drinking Water

|

Addressing water impacts on communities by building a water treatment plant for entities´ water emissions, closed water circle, minimizing use of water especially in water stress areas (communities) |

Offering special services to underserved communities (basic human needs: water)

|

|

Health |

Excellent health and safety processes in place, low rate of injuries and occupational diseases (workers)

|

Research on pharmaceuticals for rare diseases |

Table 2: Summary of the key features of the two social dimensions envisioned as layout of the EU Social Taxonomy

|

|

VERTICAL OBJECTIVES/DIMENSION |

HORIZONTAL OBJECTIVES/DIMENSION |

|

Objectives |

Promote adequate living standards/conditions for individuals and groups in situation of vulnerability |

Address potential and actual negative impacts to people and the environment linked to operations and value chains (impact on affected stakeholders & respect for human rights) |

|

Scope of |

Products and services sold |

Operation and conduct (relying on processes which need to be horizontally integrated into an economic entity) |

|

Key protagonists |

R&D, business development and marketing departments

|

CSR team, human resources and purchasing departments |

|

Stakeholders |

|

|

|

Content illustration |

|

|

|

Adequate level |

|

|

|

Sectorial sensitivity (scope of sectors) |

|

However, there are sectors with high risk of human rights infringements:

Exclusion criteria can be introduced from a DNSH standpoint, to ensure harmful sectors or activities, such as weapons, gambling and tobacco cannot qualify as socially sustainable, despite e.g. good worker-related performance. |

|

Examples of standards or benchmarks |

|

|

|

Technical criteria (AAAQ concept) |

|

|

Social factors are hardly quantifiable and influenced by context

While there are some answers in the science behind climate change to inform CO2 reduction requirements, science is not systematically able to play such a role for social factors. The Draft Report reads “Social phenomena cannot be explained by laws of nature”. Instead, social norms and standards emerge from structured discussion among stakeholders and are by their very nature prone to political preferences and cultural biases.

The Working Group examines both sector related and sector agnostic approaches. It points out the importance of contextual differences, i.e. that the variety of sectorial and geographic situations matter.

The Draft Report rightly emphasizes that there might be “a higher risk of abusing the rights of communities when building a hydro power station than when developing software”. Reversely, “impacts on privacy of end-users might be more challenging to safeguard when developing software, than when building a hydro-power station”. In addition, ensuring respect for human rights in countries in which they are not well protected might require more from companies than when operating in context with high degrees of protection.

On socio-cultural differences, the Report pinpoints that “While there would be a fairly a common understanding of availability, accessibility and quality of products and services cultural acceptance will be more difficult”.

Overall, we are in favor of taking into account contextual differences when designing technical screening criteria. However, it should not be too refined because the goal of a taxonomy is to provide market participants with a common classification and understanding. A patchwork of SC criteria based on cultural or contextual differences would fragment the market. It is therefore necessary to build up social taxonomy on internationally agreed authoritative norms and principles.

Use of the SDG and 2030 Agenda

The Report highlights that SDG indicators are quantified, however they relate to governments and not to companies. It argues that “they could however be employed to the corporate world by linking the SDG achievements and lack of achievement of a given country to the corporate contribution to these in this country”. Such linking is however hard to demonstrate, and require infra national data, focusing on locations where companies operate at a critical scale as for instance in areas where it its manufacturing capacities and/or operations are concentrated. Ensuring adequate living standards requires excellent and intimate knowledge of customers (their past, present and future situations and what products or activities they are exposed to), which is hardly the case.

The example given on improved accessibility is interesting: building and managing flats (NACE code: 41.20) where the rent is x per cent lower than the average rent in a certain area and ensuring that these flats are only rented to certain target groups like persons with low income. External factors often play a role in the economic-related situation, and it is hard to attribute causation. A good proxy could lie in customers’ surveys (see the presentation of such instrument in our Report on Social Bond Impact Reporting).

Taking into account the broad contribution of businesses?

The Subgroup questions whether a social taxonomy should “take into account the broad contribution of business to society, and its social impact for employment creation, productivity growth as well as investments in human resources that companies make in their employees”. The examples provided are pay, skills development, digital technology tools enhancing working conditions, well-being, occupational benefits, such as pensions, unemployment insurance.

In our view, such aspects should be included, and awarded whenever businesses go beyond legal requirements. For instance, the arguments fleshed out about tax transparency — benefits on trust, credibility in the tax practices, support to the development of socially desirable tax policy — call in favor of including the broad contribution of businesses. The difference made between the inherent and additional benefits of an economic activity is somehow artificial.

Areas for improvement or clarification

As previously explained the quality of this Draft Report and of its analysis and recommendations is excellent. However, we identified areas of potential improvement.

i) Designing a Social Taxonomy that can also work for public entities

The main end-users of such a Social Taxonomy are businesses and financial market participants. Nevertheless, we do believe that public entities must not be forgotten.

Taking into account private sector positive social impacts is sound and necessary, but Sovereign, Supra and Public Agencies (SSAs) must be covered in a way or another, at least when financial product related to the Social Taxonomy will be designed.

For instance, any EU Social Bond Standard could not ignore the activities and spending of governments in relation to water, housing, healthcare or education services. The concept of availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality (AAAQ) is largely applicable to them. Furthermore, many of the criteria or objectives suggested are in the almost exclusive remit of governments (e.g. affordable early childhood education and good quality care, right for the long-term unemployed to an in-depth individual assessment at the latest after 18 months of unemployment, income support for people with disabilities).

ii) The “artificial” difference between inherent and social benefits

The difference made between inherent social benefits of economic activities and additional social benefits provided through these activities is blurred. We for instance disagree with the statement that, for a pharmaceutical company, producing drugs is part of its business and cannot be considered as a substantial contribution in the social sphere. There is no reason to value only the production of drugs for rare diseases or ease the access drugs for certain groups of people. Hierarchy of economic activities based on their purpose and social value should not be ignored. There are indeed “economic activities which are essential for the fulfilment of adequate living conditions”. Done in a certain way– the examples provided are training tailored to vulnerable groups, or accessible jobs and infrastructure being created in deprived neighborhoods – they deliver further impact. The subsequent question is therefore the introduction of different levels of contribution/weighting criteria.

iii) Confusion between SC and DNSH

Often, it is not clear whether a criterion or an objective fall within the Significant Contribution or the Do no Significant Harm suggested. Sometimes, a same criterion is proposed to define both, with extra requirements or levels of action defining SC. The practicality of such continuum, notably on the basis of going beyond legal requirements, is uncertain although worth attempted. Some suggested criteria or proposals are sectoral or activity agnostic, others are not. Some criteria will even need to reflect geographical dimension, that only adds complexity. The right answer is probably a mix of the two, but one can get lost.

iv) Systematism in the presentation and hierarchization of objectives and criteria

There are many back-and-forth. The entry point is sometimes social objectives, in other cases it is stakeholders. The Report fairly explains that members of a community are often also workers and consumers, so there are obvious overlaps. Distinctions between entity versus activity are extremely helpful but not always consistently made. In other words, more systematism is necessary for the final Report.

v) Geographic contexts are insufficiently considered

One of the objectives stated in the Draft Report is of the utmost relevance: “Leave no person and no place behind”. However, the spatial dimension is little substantiated, clearly lacking guidance on how to factor geographic disparities and target lagging / deprived areas. The use of national and European public statistics identifying specific territories (cities or districts) is a powerful instrument, especially for basic economic infrastructure (e.g. transport or internet). Some methodological guidance about available data and the ways to use them could be relevant (see for instance the European Social Index).

vi) The notion of target or vulnerable population is largely unsubstantiated

There is overall a lack of definition on “people and groups in situations of vulnerability”. Furthermore, a real obstacle is also not addressed: how businesses can have a better acquaintance of their stakeholders / end-customers (to trace back the actual effect of their products or services on them). Most of the time, they do not know precisely who they are from a vulnerability characteristics standpoint (i.e. employment status, level of income or education, while preserving the privacy of end-users). The table below identifies some of socio-economic information that could be relevant to define target populations.

Table 3: list of characteristics to define targets populations

|

|

vii) Instruments to document actual impacts are absent

Above all, the necessary data, collection processes and ways to evidence positive contribution through products or services is undocumented. Indeed, methodological tools to evidence positive outcomes or impacts are not mentioned (surveys, data collection systems, modeling). One of the biggest challenges is that for climate-related matters, impacts lies in chemistry and can be assessed ex ante. For social matters, the impact is more of an ex post and in situ nature.

viii) Articulation option between various taxonomies and other European Regulations are confusing

The three models of articulations presented by the Working Group are hard to grasp. have different impacts on capital flows and by this on companies. The consistency or at least the absence of significant discrepancies between the different European norms – for instance the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) – and the future Social Taxonomy is of the utmost importance. Note that it would be easier to define environmental minimum safeguards with the creation of a brown taxonomy.

Calendar

The timeline is a bit unclear. Preliminary elements are meant to be published in June. According to the Roadmap for the development of a Social Taxonomy (in Annex of the leaked document), the Final Report on outline of social taxonomy and minimum safeguard are to be presented on October 20 and November 18, 2021. Overall structure and criteria for adequate living standards are two parallel streams of work.

[1] The Report mentions the Investor Alliance for Human Rights, the PRI 2020 Human Rights Framework, or the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark.

[2] See for example the Platform Living Wage Financials (PLWF), which is a coalition of 15 financial institutions that encourages and monitors investee companies to address the non-payment of living wage in global supply chains, available here.

[3] GRI: Business Reporting on SDG Integrating the SDG into corporate Reporting a practical guide, 2018, p.7 – available here.

[4] Source: Antje Schneeweiß (2020), A Proposal for a Social Taxonomy for Sustainable Investment, available here.