A growing momentum for Fair Transition Finance

11-minute read

Momentum is building regarding the topic of the “Just Transition.” Regulators, investors and issuers alike seem to take into account the negative social consequences the transition towards a low-carbon economy could potentially create, especially for workers and communities involved in high-emitting activities. In this light, Amundi announced earlier this month the launch of a Just Transition Fixed Income Fund while the World Benchmarking Alliance launched a consultation on social indicators as part of a pilot project aiming at benchmarking the “just transition scores” of 2,000 companies in 2022 (integration into environmental assessments of the ACT methodology) .“Just transition” takes root in investors mind and more countries view it as an integral part of their energy transition: Canada and the United States developed Just Transition Task Forces for coal power workers and communities.

Defining a “Just Transition”

To understand the concept of a “Just Transition” or “Fair Transition”, one should first define the limits of what exactly this transition involves. The need for “fairness” arises from the redistributive impacts of any given transition resulting from a new paradigm, such as a carbon-constrained world. It could also be related or intertwined with technological breakthroughs (AI is often mentioned, as it enables automation that will destroy jobs). Therefore, a low-carbon fair transition refers to an interim period and process by which a company transforms its business model and activities in order to become low-carbon while “leaving no one behind” (European Commission formula). It requires to make sure negative social impacts are minimized as some sectors are likely to disappear from the transition (coal, ICE vehicles manufacturing), or adapt for practically every industry.

In the context of the transition towards a lower-carbon economy, companies can act upon five levers (see our article regarding our latest flagship report):

- Quitting / exiting high-emitting activities and assets by divesting or decommissioning (dark brown activities that are very harmful)

- Diversifying the business model by increasing the share of low-carbon activities (activities mix greening)

- Decarbonizing core and often hard-to-abate activities through investment in new manufacturing processes, technologies, materials.

- Offsetting remaining GHG emissions through negative emissions (forestries, CCUS)

- Developing low-carbon or decarbonizing solutions and products enabling the transition in other sectors.

The quit / exit, the diversify, as well as the decarbonize levers infer a shift of the way business units operate at a corporate level, which, in turn, entails a transfer of skills and workforce. In this light, workers and communities in high-emitting sectors are set to bear most of the social consequences of the transition, but regions whose economies are relying on these industries are likely to suffer to. As such, these social externalities are not only linked with a decrease in revenue, but also with psychological and social externalities in case of increased unemployment.

Thus, a fair transition refers to a piloting and governance of efforts made by a company to avoid, minimize, or compensate social negative impacts arising from its transition, especially regarding employment. Nevertheless, it is imperative to bear in mind that in order to ensure a fair transition, the effort should not solely focus on employees and their reskilling but also on the development of carbon-neutral infrastructure and financial incentives targeting regions that were relying on high-carbon industries.

For us, a Fair Transition is a concept that goes beyond the mere scope of the corporate transition and we view it as a transition where the benefits of shifting towards a lower-carbon economy are widely shared and in particular with communities and groups that work in high-carbon emitting sectors, or are vulnerable to the physical effects of climate change (people living in coastal areas, farmers).

The transition towards a low-carbon economy should not widen existing and increasingly less tolerated inequalities but rather “engined” and steered to narrow them.

A Fair Transition is thus not static, but rather a continuing process that involves a balanced and equitable governance between those suffering and those benefitting from the transition. The latter cannot be harmless or painless per se. Non punitive ecology is a fantasy, but what is vital is to protect and compensate the stakeholders being hurt.

At company level, a Fair Transition is mostly about the efforts to avoid, minimize, or compensate the negative social impacts that tend to arise from a transition towards a decarbonized economy, especially with respect to employment.

How can workers be affected by the transition towards a lower-carbon economy?

One can identify four ways in which jobs are affected by decarbonization strategies:

Job destruction, transformation and substitution are more likely to happen in and to impact high-emitting sectors but also in those that will or are already experiencing significant structural changes in the way they operate, in the manufacturing processes and in particular in automation. In table 1, the European Commission evaluates evolutions of employment in each sector as following:

Table 1. Employment evolution by skill level (%)

Source: European Commission (2020), A Just Transition Fund

Agriculture, mining, manufacturing, construction and transportation are considered sectors on which the transition will create important social impacts. Research shows these sectors are also considered high-risk in terms of human rights rights as defined in the UN Guiding Principles and the working group on social taxonomies of the EU Sustainable Finance Platform is to develop new sets of minimum social safeguards by the end of 2021 to tackle these risks in a more consistent manner[1].

In our Transition Tightrope series’ interview, the economist Patrick Artus told us about how the European car industry could lose 700,000 jobs in the battery sub-sector as Asia will be more competitive to build them. The losses will also be very localized and touch entire regions according to him because “car making is concentrated in few territories” (see the interview “low-carbon transition agenda: avoiding social quicksand”).

Mitigating social consequences of the transition does not only entail mitigating the impacts of job destruction, but also from job and skill relocation. In many cases, workers are not the only impacted, as communities surrounding industrial sites can suffer due to workers’ relocation or a decrease in tax revenue. Indeed, surrounding public services could indirectly deteriorate due to decreased revenue (taxes) from the industrial sites and from the local economic activity.

The mechanics of a “Just Transition”

A corporate transition towards a lower-carbon business model is a process that must be holistic and consistent, and it is not so much about micro improvements or singular solutions for specific assets like plant decommissioning (though it can involve it). It is rather a dynamic process requiring efforts at almost every level (governance, R&D, CAPEX). Due to its very nature, a Just Transition is set to be a multi-stakeholder process and dialogue between workers, unions, and companies. As such, asset owners are responsible for the allocation of a share of their investment into accompanying certain populations that are confronted with the dismantlement of industrial sites. Negative social consequences can also arise from the decarbonization of manufacturing processes which might require less workforce to operate.

Consequently, fair transition can include the involvement of workers and unions in the planning of the transition strategy (for instance, the utility SSE includes this dialogue component within its Just Transition governance strategy); the identification of the jobs that are the most at risk; the retraining of workers towards low-carbon jobs when possible; the possible repurposing of fossil fuel facilities (converting coal TPP into biomass plants) before actual asset decommissioning or disposal; human resource services like training, redeployment, career advice.

In the context of sustainable finance, one believes these measures could become eligible proceeds in a green financing instrument as these expenses are necessary to pilot a smooth and coherent transition.

[1] More information available inn Antje Schneeweiß, “A Proposal for a Social Taxonomy for Sustainable Investment” – available here.

Title 1. Mechanics of a Just Transition at a corporate level and challenges for various stakeholders

Source: Natixis GSH

Going through the process of evaluating how an asset can serve the corporate transition through repurposing in the first place (1) is one of the first steps to both decarbonize the activity and maintain a good share of employment. Indeed, the existing workforce can be trained to operate a gas-fired or biomass plant instead of a coal fired plant. If repurposing is not possible and decommissioning is the only solution, existing workers can be involved in the process as well. Employees that have low employability should be prioritized in further policies (2). As a company transitions and develops low-carbon activities if its business allows it to, the wealth generated from them can be utilized and directed towards the workers that are entitled to benefits (3). In a more global context, public authorities also have a role in piloting a fair transition for regions that relied on highly-emitting sectors (see the Just Mechanism below). Besides mitigating impacts of decreased revenue in impacted worker’ populations and communities, companies should coordinate with public authorities to provide social and even psychological services to guarantee a smooth return to employment if possible (4). Finally, retraining, reskilling programs, as well as guidance to integrate low-carbon sectors within the company are measures that are the most suitable and coherent to facilitate a corporate fair transition.

Anticipating and mitigating the impact of the transition on specific areas and social groups

On a national and even supranational level, the fair transition concept can as well be translated into solidarity measures and easing environmental taxes or restrictions for isolated areas or for specific social groups. For instance, in the 2021 budget of France (see our article on France’s mapping of its green and brown expenses in its 2021 budget), there is a fiscal expense worth € 1,745M of reduced rates of tax on the consumption of energy products for the overseas departments as well as € 1,420M worth of a reduced rate for non-road gas, oil and heavy fuel oil used for agricultural and forestry work. In the French strategy to end public support to fossil fuel export projects (see our article), the rule is to not support projects that increase the carbon intensity of the electricity mix of recipient country, but exceptions are applied for projects that are i) necessary to the stability of the grid, ii) are located in areas where low-carbon projects are impossible to develop due to interconnexion difficulties for instance.

On the other side of the spectrum, programs seeking the widespread distribution of the benefits offered by the transition towards a low-carbon economy can be implemented by public authorities. As such, incentives like forfaitary aids to acquire efficient or low-carbon vehicles or building equipments preferably distributed to households with low revenue could be an option as these investments can as well decrease the energy and transport costs for these households. In the context of a Fair Transition, an example of sharing the benefits of the transition could thus be the MaPrimeRénov’ (more information available here) measure that subsidizes a share of refurbishing works with revenue conditions favoring low-income households.

Finally, the concept of Fair Transition can be through the spectrum of carbon inequality. If we look at carbon budgets on a more granular way, we realize for instance that a bigger share of this budget is consumed by the top 10% wealthy households. Strikingly, from 1990 to 2015, the income groups that reduced their per capita GHG emissions per year the most were those with lower incomes while the top 1% richest increased their per capital consumption emissions.

Table 2. Per capital consumption emissions (tCO2/year) by EU income group in 1990 and 2015

Source: Oxfam, The Carbon Inequality Era (September 2020) – available here.

Focusing on the “Just Transition Mechanism”: expanding the scope of the Fair Transition

A Fair Transition is not just about a company’s transition. It can also be thought on a bigger scope like on a national level: President Biden’s measure to create a Task Force on Coal and Power plant communities is an example of how a Fair Transition can be designed on a national level.

At the EU level, the European Commission unveiled in 2019 “The Just Transition Mechanism (JTM)” (see Green Deal Communication, December 2019), which serves as a key tool to guarantee a fair transition for citizens, companies, and regions. It forms an integral part of the investment pillar of the European Green Deal. The JTM is the EU’s holistic attempt to ensure the economic, social, and territorial transformation of duly target regions that would be directly impacted by the energy transition. As such, the JTM will aim to guarantee the transition towards a climate-neutral economy in an equitable fashion, leaving no region behind. The JTM’s support mainly focuses on regions that are either highly carbon intensive or with most people working in the fossil fuels sector. Regions can access funds by preparing elaborate territorial just transition plans, which address both the human and non-human elements of the transition. These entail the inter alia the following:

- People and citizens: facilitating new employment opportunities, re-skilling schemes, energy efficiency

- Companies and sectors: support for transition to low-carbon energy technologies, climate-resilient investment and jobs creation, easier access to loans and financial support

- Member states and regions: providing technical assistance, providing affordable loans to local authorities

In order to unlock the support available to Member States, the EU has created the “Just Transition Platform,” which serves as the single access point for support and knowledge regarding the transition. The platform allows Member States to access the financing schemes proposed in the JTM, which are three-fold.

- The Just Transition Fund (JTF)

- Just Transition Scheme under InvestEU

- EIB Loan Facility backed by the EU badget

These financing mechanisms will steer new investments towards beneficiary regions that are considered negatively affected (see eligibility criteria below) by providing both technical assistance via the Platform and creating attractive conditions of risk sharing between public and private investors through financing schemes.

Pillar 1: The Just Transition Fund will provide grants for SME investment, skilling of workers, transformation of carbon installations to support economic diversification and reconversion in affected regions. € 40 bn worth of grants are to be distributed (if Member States match each euro received from the fund with 1.5 to 3 EUR from their own budgets). The criteria for a region to be eligible include:

- Greenhouse gas emissions of industrial facilities in regions where the carbon intensity of those emissions exceeds the EU average.

- The level of employment in the mining of coal and lignite.

- The production of peat.

- Production of oil shale

Following an open call to application to the Secretariat Technical Assistance to Regions in Transition program that addresses gaps in already existing technical assistance available to EU coal regions, seven regions were selected for their socio-economic structure, geographic attributes and exploited resource: Asturias (Spain); Jiu Valley (Romania); Karlovy Vary (Czechia); Małopolska (Poland); Megalopolis /Peloponnese (Greece); Midlands (Ireland); Silesia (Poland) as identified in title 2.

Title 2. Regions most at risk* according to European Semester Country reports

*The country reports published in the European Semester provide a qualitative method, based on a multitude of regional criteria and information, to identify the most vulnerable regions in each country. The criteria used vary from country to country and include statistics such as employment in declining industries, regional development, unemployment rate, youth unemployment rate and the composition of the population by age and sex

Source: European Parliament, “A Just Transition Fund” study (April 2020) – available here.

Pillar 2: The InvestEU Scheme aims at financing the specific transition objectives of Member States. The InvestEU program will not only support investment to beneficiary territories (regions having an approved a Transition plan under the Just Transition Fund rules), but also in regions that will benefit the just transition territories. Different from the Just Transition Fund, the InvestEU scheme supports a wide range of investments, particularly in infrastructure. There is a great focus on projects for energy and transport infrastructure, including gas infrastructure and district heating, but also decarbonization projects, economic diversification and social infrastructure.

Pillar 3: The EIB Loan Facility allows for public sector entities with resources to implement measures to facilitate the transition to climate neutrality. The EIB loan facility will ultimately aim at leveraging public and private investment to support investment in just transition territories in the sectors of energy, transport, economic diversification and social infrastructure through loans.

As the Just Transition Platform will target regions but also sectors and industries, this means that high-emitting companies are likely to benefit from the JTM in case they provide a clear strategy to develop lower-carbon technologies and activities while mitigating negative social consequences of the transition. The development of social objectives by the Platform on Sustainable Finance to extend the EU taxonomy (report on social objectives dues by Q2 2021 and report on minimum social safeguards by Q4 2021) will likely enhance the incentives to design transition pathways that consider environmental and social objectives deriving from the transition hand-in-hand in the foreseeable future, giving credit to Fair Transition initiatives like the Just Transition Plan of Scottish and Southern Energy.

Investors’ interest grow and sovereigns develop just transition plans

According to our 2019 Investor Survey on the transition of Brown Industries, 40% of respondents would, for instance, consider retraining programs for the workforce as eligible proceeds of green financial instruments. This percentage is too low in our view. The reluctance may come from the lack of information about workers management and reskilling necessary. In our opinion, most high-emitting companies would benefit from developing Fair Transition Bond frameworks (either for KPI-linked instruments of Generate Corporate purpose instruments) or extending their Green Bond frameworks towards eligible categories that mitigate negative social consequences of their transition.

The ICMA Transition Bond Handbook considers this opportunity and while there is not yet a clear definition of what a Transition Bond would look like (see our article on the creation of a Transition Bond segment by the London Stock Exchange), future standards might indeed qualify social expenses as eligible proceeds of Transition financing instruments.

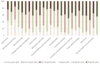

Title 3. A nascent “Just Transition” landscape: recent announcements

Sources at the end of the article

We indeed believe financial instruments including fair transition indicators will develop over time. Both Canada [2] and the United States [3] created Task forces for Coal workers and communities and the EU unveiled the Just Transition Mechanism in 2019. The current development of transition taxonomies by Canada and Japan will put on the regulatory agenda the necessity to not only think about low-carbon activities and their development, but also about the transition of high-carbon activities which will drive Fair Transition challenges forward as well. In this context, the forthcoming extension of the EU Taxonomy to Social Objectives and the attention given to social issues, especially during the Covid-19 crisis, will not only steer investments towards social “pure” activities and players, but also towards highly emitting companies that will develop coherent Just Transition strategies similarly to regions applying to the Just Transition Platform.

To go further:

- Scottish and Southern Energy, “Supporting a Just Transition” (November 2020) – available here.

- International Capital Markets Association (ICMA), Climate Transition Finance Handbook (December 2020) – available here.

- The White House, Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad – section 219-223 on Environmental Justice (January 2021) – available here.

- European Commission, access to “The Just Transition Mechanism” documentation

- World Benchmarking Alliance, access to the “Just transition” section covering the approach to the Just transition assessments benchmark

- Amundi Asset Management, access to the “Just Transition for Climate” documentation