The European Union's plunge in the Social Bonds Market

- 9-minute read -

The Covid-19 pandemic and widespread lockdown measures have severely slowed down the economies of many countries around the world. European real GDP is now projected to contract by 7% in 2020, its biggest decline since World War II[1]. Across Europe, in order to maintain employment and limit the effects of this economic crisis, governments are resorting to large fiscal and financial support packages and job retention programs.

In May 2020, more than 40 million people in Europe had part of their salary paid by EU Member States[2]. These emergency measures, which aim to avoid mass layoffs and associated social consequences, have naturally increased the European States’ debts.

Source: Eurostat

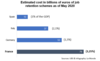

With an unemployment rate that could rise from 7.3% in early 2020 to 9.5% in 2021 in the European Union (EU)[3], many European governments decided to extend their emergency measures to save jobs while waiting for the economic recovery through stimulus packages. France allows firms to invoke the health crisis as “force majeure” to use its Activité Partielle, a provision companies can use to reduce the activity of their employees. All employees with a contract in France (whether permanent or not) are eligible and receive 70% of their gross wage from the employer. During the COVID-19 crisis, most employers do not bear any cost for hours not worked, as the state reimburses what they pay to employees up to a cap of 4.5 times the hourly minimum wage. Germany and Italy have already allocated €10 billion to strengthen the Kurzarbeitergeld and la Cassa integrazione Guadagni, respectively, which are institutions providing financial support to unemployed people. Italy, which was particularly affected by Covid-19 in the first half of 2020, has taken social security and employment support measures (compensation for short-time working has been extended until December 2020, paid by the State for the first nine weeks).

At the end of the second quarter of 2020, the government debt to GDP ratio in the euro area stood at 95.1% (compared with 86.2% at the end of the second quarter of 2019[4]). The highest ratios of government debt to GDP at the end of the second quarter of 2020 were recorded in Greece (187.4%), Italy (149.4%), Portugal (126.1%), Belgium (115.3%), France (114.1%), Cyprus (113.2%) and Spain (110.1%). Job retention schemes adopted across Europe are one of the drivers of the increase of public deficit (although their social but also economic benefits in the medium and long term are likely to exceed their upfront cost) as they have a cost often exceeding 1% of the GDP (see graph below).

To alleviate the countries’ debt burden, the EU developed an emergency aid program called “Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency” (SURE), which is entirely meant to be financed through Social Bonds issued on the debt capital market. In addition, the EU is also operating three loan programmes to provide financial assistance to member States and third countries experiencing financial difficulties: the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM ), the Balance of Payments programme (BoP) and the Macro-Financial Assistance (MFA)[5]. All four programmes are funded through bonds issued on the capital markets. To this end, the European Commission is allowed to contract borrowings on the capital markets on behalf of the EU.

What is the SURE instrument?

SURE is a new temporary instrument. The European Commission depicts it as the “emergency operationalization of the European Unemployment Reinsurance Scheme”[6]. It offers a financial assistance of up to €100 billion in the form of loans from the EU to Member States experiencing a sudden and severe increase in public expenditure for the preservation of employment and healthcare services. The financial assistance complements national measures and is channeled by the EU to beneficiary Member States in the form of loans granted on favourable terms. The SURE instrument is based on voluntary requests from affected Member States of the Covid-19 crisis in terms of employment and healthcare. All Member States are eligible to the instrument. It is backed by a system of voluntary guarantees from the EU’s national governments worth €25 billion. The SURE program is decorrelated from the Next Generation EU- Recovery Plan.

The SURE program is attractive for countries with weak fiscal positions, such as Spain or Italy, for which SURE loans are likely to be cheaper than their own borrowing costs, albeit with relatively shorter durations. The terms on which the Commission borrows are directly passed to the Member States receiving the loans (back-to-back loans). The European Council has already approved a total of €87.9 billion in financial support for 17 Member States (and additional €2.5 billion proposed for Ireland to be approved). The latest Commission proposal brings the overall financial support under the SURE programme to €90.3 billion. €31 billion have already been paid to Italy, Spain, Poland, Greece, Croatia, Lithuania, Cyprus, Slovenia, Malta and Latvia.

The amount of loans granted is decided by the European Council, based on the proposal from the Commission, considering the needs of the requesting State. Since SURE is a temporary instrument, the Commission will assess every six months whether the exceptional circumstances that caused the economic disruption in the Member States still exist.

Infographic 1 - SURE: eligible countries and financial assistances in €

Source: European Commission (2020)

The first steps of the European Union in the Social Bonds market

On October 27, 2020, the European Commission issued a €17 billion inaugural Social Bond under the EU SURE instrument to help protecting jobs and ensure job positions in the most affected countries of the COVID19 crisis of the EU. This inaugural Social Bond has been followed by two other issuances on November, 10 and November, 24, reaching €39.5 billion so far of the contemplated €100 billion of Social Bonds as announced by Ursula Von Der Leyen in early October (If the maximum level of €100 billion of financial assistance is reached).

The issuance on October 27th consisted of two Social Bond tranches:

- A first 10-year maturity tranche of €10 billion

- A second 20-year tranche of €7 billion.

It was the world’s largest Social Bond ever issued.

The issuance was a real success, the bonds were more than 13 times oversubscribed (with orders in excess of €233 billion). The 10-year tranche was priced at 3 bps above mid-swaps; premiums estimated at 1 bps; yield of -0.26%. The 20-year tranche was priced at 14 bps over mid-swaps; premiums estimated at 2 bps[7].

On November 10, 2020, the EU issued a second Social Bond, in two tranches, for a total amount of €14 billion. This second issue was also successful, with final books of €85 billion (5-year tranche) and €55 billion (30-year tranche).

On November 24, 2020, the EU issued a third Social Bond for an amount of €8.5 billion with a maturity date of 15 years. The bond was more than 10 times oversubscribed with an order book in excess of €90 billion.

Currently, the EU has roughly €50 billion of outstanding bonds apart from its Social Bonds, most of which were used to fund loans to Ireland and Portugal during the region’s debt crisis for the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM) and the remainder for a Balance of Payments (BOP) loan program. Meanwhile, on 16 September 2020, the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen announced a €225 billion Green Bond issuance program, representing one third of what the EU intends to raise on the markets to finance its post-Covid recovery plan, through its NextGen recovery plan.

Since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, a strong development of the social bond market has been observed (as pointed out in our article “Market overview Covid-19 Responses-related Bonds” published in April 2020). Measures were under scrutiny, especially support to companies, with a strong push from civil society and various political and economic stakeholders to include string of social or environmental conditions.

In this respect, Unédic issued several Social Bonds (for a total of 17Bn€ since the outbreak of the pandemic) to finance unemployment insurance in France, a deal structured and arranged by Natixis (see our dedicated article). Many international organizations, particularly development banks (i.e. African Development Bank, International Finance for Facility for Immunisation) have also issued Social Bonds to finance the major needs of their systems to fight against the pandemic and to address its impacts. Commercial Banks are also present on that market thanks to loans provided to SMEs in distress (BBVA and Caixabank in Spain, Credit Mutuel Arkea in France for Europe, Bank of America in North America as well as Bank of China in China, South Korean Kookmin Bank and Shinhan Bank and Mitsubishi UFJ for Japan in Asia), as well as public banks (CAFIL, Italian Cassa Depositi et Prestiti and Spanish Instituto de Credito Oficial (ICO)).

As a whole, bond issuances related to Covid-19 (bear in mind there is neither canonical definition nor a standard on Covid -19-related issuance) are estimated to have reached a global amount of USD 136,9 billion[8]. SURE Social Bonds clearly participate in this market and increase the liquidity available on the market.

EU’s Social Bond Framework

In order to benefit from the SURE mechanism, each Member State will have to provide evidence of a sudden and severe increase in actual and possibly planned public expenditure on short time working programmes or similar measures. In the event the government applies for financial assistance for health-related measures (i.e. particular at the workplace, used to ensure a safe return to normal economic activity), the government will also need to provide evidence of actual or planned health-related expenditures.

The Commission has established a Social Bond Framework[9] in accordance with the Social Bonds Principles (SBP) published by the International Capital Market Association (ICMA). This Framework was reviewed by Sustainalytics[10], that gave a favourable Second Party Opinion. It considered that the Framework is fully aligned with the Commission's social and economic strategy and with the Social Bond Principles.

All in all, the EU is poised to account for the largest portion of future social bond issuance, reflecting its unique position and echoing its bold sustainable finance agenda. With the SURE Social Bonds and the recovery plan, the European Union will become one of the largest issuers on the continent.

What are the next steps for the EU?

The scope of the EU SURE Social Bonds Framework will be further extended in the future to include potential EU green, social and sustainability bonds as issued under the Recovery Plan (possibly through an overarching framework). It is EU’s stated ambition to align future EU bonds with the forthcoming EU Taxonomy for environmentally sustainable activities. For now, to avoid any confusion, the bonds under the present Framework will be named “EU SURE Social Bonds”. The Framework specifies that these bonds are not prefiguring the social part of the future EU Taxonomy nor a possible action of the Commission in the area of the EU Green/Social Bond Standard.

The uniqueness of such social bond program is definitely its unprecedented size in a trans-sovereign format matching unprecedented emergency measures across Europe, some of which likely to turn ito medium to long term mechanisms.

From a sustainable finance perspective, time will tell whether this gigantic social bond program is set to introduce innovation in what remains often a challenge : the measurement of social impact of such programs, especially considering the discrepant levels of transparency and impact evaluation practices across EU members.

Regulators and policymakers increasingly pay heed to social topics when dealing with sustainable finance. The EU Taxonomy Regulation encompass a review clause and has tasked the EU Commission to publish a report by December 31, 2021 on the inclusion of other sustainability objectives, including social (§59 of the Regulation). A task force on the development of a social taxonomy has been created in October 2020 within the Permanent Sustainable Finance Platform. It is chaired by Antje Schneeweiß (Südwind Institute), author of a report titled “Human Rights Are Investors’ Obligations – A Proposal for a Social Taxonomy for Sustainable Investment”.

In order to enlarge the scope of a social taxonomy beyond the paramount defense of Human Rights, which could be considered as an expected fundamental requirement in all activities, , we believe that the 2030 Agenda provides rich guidance on activities fulfilling essential needs and achieving social outcomes around nutrition, education and training, health, housing, mobility. It can serve as a good starting point to draft the European social taxonomy.

Early November, the Council of the EU and the European Parliament reached an agreement on the 2021-2027 EU budget, putting the EU one step closer to implementing its historic €1.8 trillion budget-and-recovery package. The deal — which still requires final consent from both the Parliament and Council — opens the way for the seven-year budget to come into effect in January.

[1] IMF (Oct 2020), Regional economic outlook: Europe, available here

[2] Le Monde (May 2020), En Europe le filet de sécurité du chômage partiel, available here

[3] European Central Bank (ECB)

[4] Eurostat Quarterly Governement Debt, available here.

[5] The EU may assist third countries experiencing a balance-of-payment crisis with grants and/or loans on the basis of individual decisions of the European Parliament and of the Council. The instrument is designed to address exceptional external financing needs of countries that are geographically, economically and politically close to the EU.

[6] The SURE : It in no way precludes the establishment of a future permanent unemployment reinsurance scheme. EC Europa (2020), Questions & Answer, available here

[7] UE (Octobre 2020), Press release, available here

[8] Source : Natixis GSH 2020 & Bloomberg Sources

[9] EU SURE (2020), Social Bond Framework, available here

[10] Sustainalytics (2020), SPO EU Sure Social Bond Framework, available here