Release of our study the New Geography of Taxonomies

4-minute read

Following our recent article “Sustainable Taxonomy development worldwide: a standard-setting race between competing jurisdictions” (July 2021), we have just released our dedicated report “the New Geography of Taxonomies”. It is benchmark built upon our own Taxonomy assessment grid. It has been designed as a handbook to navigate a complex landscape of more than 16 taxonomies worldwide (from the EU obviously, but also China, Mongolia, Russia, Singapore, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Kazakhstan, United-Kingdom, Mexico, Georgia, Chile, Japan, Singapore, South-Africa, ISO, CBI, ASEAN, mostly green, but also social or transition).

In the field of sustainable finance, guidelines and standards are the bedrock of product design and market integrity. Investing and funding strategies need anchoring definitions and if not undisputed, official criteria. It holds true as well for governments in their attempt to greening their interventions or spending. In order to introduce environmental caveats or string of conditions in recovery / stimulus packages, subsidy or taxation systems overhauls, policymakers have an urge for a common understanding on what is unarguably (or consensually) sustainable, and a one consensual for all their stakeholders.

Taxonomies of sustainable activities are the linchpin of sustainable finance and aim at providing clarity and standardization to market participants. Put simply, a sustainable finance Taxonomy (hereinafter “a Taxonomy”) is a classification tool. In China, it is referred to as “Catalogue”. Taxonomies serve as a technical guidance and disclosure yardstick.

Taxonomies usually identify specific economic activities (based on economic nomenclatures), technologies or set of conditions (performance improvement against a baseline) – ideally with quantitative and technical thresholds anchored into scientific & industry evidence. Currently, these classifications have heterogeneous degrees of regulatory & binding strength. The stringency of their criteria varies as well. When calibrated on performances and pathways consistent with low-temperature scenario (1.5°C or well below 2°C), technical criteria are inherently difficult to achieve.

Greenwashing is a plague (see our article this month) and incremental progress are unfit to cope with the climate emergency. However, restricting Taxonomies to dark green levels of performances drastically reduces their comprehensiveness and sectorial coverage. It comes with the risk of reducing the pipeline of eligible activities or entities to a niche. It is turning a blind eye to the bulk of our economies, discouraging or postponing the decarbonisation of transition forerunners operating in high-emitting industries (see our Series Brown industries: the transition tigthrope). In contrast, shaded Taxonomies are attractive, but they add massive complexity.

Each Taxonomy strikes a balance between comprehensiveness (sectorial span, amount of GHG emissions covered, number of activities reviewed, level of granularity and sub-categories granularity), sophistication (criteria refinement, intermediary levels, cumulative set of conditions, ESG safeguards), usability (nature and complexity of the demonstration and verification process, data inputs required) and stringency (ambition level of the criteria, i.e. whether it is out of reach for most corporates). This set of criteria determine the acceptance of a Taxonomy, which also depends on the involvement of its recipients or users at the different life stages of the classification (presence of advisory groups, consultation, grievance mechanisms, criteria updates).

Science-anchorage and actors’ ownership are equally paramount. On the medium to long-term, we believe that Taxonomies not immune to the denial of science by political and economic lobbying are doomed. In Europe, discussions around gas and nuclear have much delayed the Taxonomy criteria adoption. Taxonomies are the receptable of economic and regulatory turf wares. When developing and promoting their “own” Taxonomies, policymakers pursue soft power and influence aims. The economic weight of a country or regional zone and the role played by its currency and law in international business affairs determine the global reach its Taxonomy could exert. Obviously, the intrinsic features of its Taxonomy criteria ̶ comprehensiveness, sophistication, usability, stringency, acceptance (mentioned supra) ̶ amplify or diminish this influence.

Table 1 – Natixis GSH’s analysis grid

|

Criteria |

Description |

|

1. Progress status |

- About different life stages of the classification (announcements/rumors, mention in sustainable finance roadmaps, drafts, final version, adoption & implementation), with details on different authors/contributors. |

|

2. Stated goals & use-cases |

- Each jurisdiction establishes a Taxonomy according to its political needs, priorities and constraints, as well as the primary users targeted. - Taxonomies can contribute to combat greenwashing, improve disclosure? reduce market fragmentation, help monitoring progress, equip companies with guidance, greening public policies (climate conditionality), touch upon financial regulation or supervision. - Depending on criteria and thresholds and the level of integration of the Taxonomy into other regulations or schemes, it can create strong alignment incentives and become a keystone of sustainable finance policies. |

|

3. Sustainable objectives addressed |

- Entities and governments display different regulatory frameworks according to their geographic and economic context (decarbonization profile, acuteness of pollution and biodiversity erosion issues). - The same environmental goals are often labeled differently from a Taxonomy to another. - The purpose can be to define significant contribution and/or significant harm (ex: “socially beneficial activities”) or transition criteria. |

|

4. Sectors covered |

- Coverage of varying scopes of economic activity and geography with use of pre-existing economic sector classifications sometimes adapted to environmental themes. - Focus varies between purely green activities, intermediate levels, fossil fuels and/or brown assets |

|

5. Typology of criteria |

- The nature of criteria depends on the sectorial coverage, pursued objectives and ambition of the Taxonomy. - The type of criteria used can include international standards and definition, national norms or regulations, relative or absolute performance of products, services, activities, etc. - Additional criteria can be used to apply ESG negative screening/Minimum Safeguards. The ambition/stringency in terms of climate change pathway or sustainability is expressed by the criteria and thresholds. |

Source: Natixis GSH

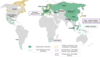

Various authorities have taken up the challenge of developing Taxonomies, which are often straightforwardly linked to Green Bonds. Twenty classifications are either announced, under development or adopted worldwide. Taxonomies mostly address climate change (16), but other environmental or even social themes are increasingly addressed. So-called transition or brown Taxonomies (3), but also social or SDG-related ones (2) are in the making. Articulating them is not an easy task for policymakers and Taxonomies recipients and users. There are spillovers between them. For example, the strictest and the most used a green Taxonomy is, the higher the needs for fair transition financing and criteria become.

Figure 1 - Overview of existing and under development classifications of activities*

* This study was mostly conducted in the first half of 2021. Numerous other initiatives have emerged since then and announcements keep growing. Therefore, a number of taxonomies projects are not covered in this study, or not in details. For instance, the Korean Taxonomies, but also initiatives from Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines, Thailand, Colombia or New Zealand.

Source: Natixis GSH

The EU Taxonomy remains the most comprehensive and sophisticated one, but the global standard setting race just kicked-off. The forthcoming “Common Ground Taxonomy” meant to identify the commonalities of existing Taxonomies is likely to help but will not be a silver bullet. One expects the United-States to catch-up and bring forward its “own Taxonomy” shortly, or at least to promote its proprietary approach of ESG.

Beyond coexistence and articulation challenges, Taxonomies must evolve over time to incorporate state of the art scientific knowledge and adjust criteria stringency on the latest performances progress towards collective goals achievement (e.g., the more we exhaust our remaining carbon budget, the stricter the technical criteria must become). By their nature, although necessary, Taxonomies updates will create legal uncertainty for market participants, and require remedy measures around retroactivity limits or grandfathering clauses.