Green-washing allegations are jolting the financial industry: heightened needs for cautiousness, integrity and guidance

31-minute read

Executive Summary

ESG and sustainable finance markets are soaring and so are greenwashing suspicions and legal risks. The SEC and BaFin’s probes against DWS for overstating its ESG integrated AuM figures attest that trend. There is a market fad for still largely voluntary and self-labeled sustainable finance products. Part of this ESG boom is inflated by so-called “sustainable washing” (“sustainable” should thereafter be interpreted as including green and social, and more broadly ESG or SRI). Sustainable washing refers to abusive marketing practices where the sustainability benefits of a product, a service or a strategy – it could be a vehicle, a savings product, or a zero-deforestation commitment – are exaggerated or misrepresented, and thus misleading. The lack, or glut of ongoing standardization, is most likely largely conducive to such abuses. Third parties and external verifiers are suffering from a lack of absolute legitimacy in the eyes of market participants, at least by supervisors, which are contemplating accreditation systems. This is the case for the EU-Green Bond Standard governance where the ESMA would act as a watchdog of second-party opinion providers.

Financial supervisors’ firm willingness to take on greenwashing is a turning point. This echoes the involvement of another key protagonist in the climate action ecosystem: judges and Courts are seized to deal with the discrepancies between climate necessity, companies or States’ claims and actual actions (see our article “Dutch Court ordering Shell to reduce its emissions, thereby harbingering a climate litigation era”). For businesses, mitigating green and sustainable washing risks will be challenging yet crucial to avoid further legal, reputational and adverse market impacts.

ESG washing probes from supervisors and climate lawsuits before Courts are intertwined: in a backdrop of climate emergency and unsustainable economic and emission pathways, on one hand, companies are accused of doing “wrong” or “not enough” (proceedings mostly aim at halting projects deemed harmful, ordering upward adjustment of their targets, and/or deepening implementation efforts), on the other hand, businesses are incriminated for overstating the merits of their performances or actions and misleading their stakeholders (greenwashing accusations).

This article aims at signaling and analyzing the ongoing legal paradigm’s shift in sustainable finance. It will start by broadly exploring the notion of “sustainable washing”, the forms it takes and the legal risks it brings in a wide range of industries (Part I). It will then focus on how the boom of sustainable finance exposes financial actors to increased liability risks due to heightened scrutiny and stricter regulations’ prospect (Part II). This study shaped our view and headways to support our clients in preventing sustainable washing (Part III).

The recommendations we have assembled are based on a review of the legal grounds, especially the BaFin, the SEC and the AMF’s nascent doctrines on ESG washing. Anticipating their consequences and meeting financial regulators’ expectations will be part of our advisory services in the next months. It is our responsibility to do so, and we always put integrity at the heart of our offer for the benefit of all stakeholders, the Bank and its clients.

To avoid falling into sustainable washing practices, firms should be working towards more authenticity, measurability, and proportionality. Consistency between sustainability approaches, marketing and communication materials is key. Meanwhile, impact assessment and dedicated reporting could become more than a nice-to-have. They could play a decisive role in the endeavor to guarantee the credibility and integrity of alleged sustainable finance products. Indeed, efforts to evidence and disclose the positive outcomes achieved through investments help combatting sustainable finance washing. When there is no impact-related data nor materials to disclose at all, it should often be seen as a red-flag or warning.

In the end, mastering existing or upcoming taxonomies of sustainable activities (see our article on our recently released benchmark), advertising and marketing with restraint and proportionality, committing to impact assessment and disclosure, are complementary actions. Such a 360° sustainable washing risk management requires an entity-wide approach.

The inherent diligence of legal, risks and compliance departments can help moderate claims and introduce systematic vetting systems and processes. One can distinguish three steps in the mainstreaming of ESG or sustainability topics across organizations, especially financial institutions: sustainability began to be handled by communication, marketing and CSR departments, it was then endorsed and put in motion by front-officers and business lines alongside top management growing awareness on the materiality and business potential of the topic, and it is now percolating into public affairs, risk, compliance, IT, human resources departments to be fully embedded into entities operating model.

CONTENT

Executive Summary

Foreword: SEC & BaFin investigations against DWS for alleged “ESG washing”: the latest evidence of an ongoing backlash.

Part 1: Sustainable washing takes multiple forms and occurs in a wide range of industry

1. What is sustainable washing?

2. What forms is it taking? What are the red flags?.

3. Are there industries more prone to sustainable washing?

4. What are the risks associated with sustainable washing?

5. Focus on litigation and liability risks.

6. What are the legal grounds suitable to sustainable washing?

Part 2: With the boom of sustainable finance, financial actors are increasingly exposed to sustainable washing risks.

7. Focus on Green or Sustainable self-labeled financial products.

8. How financial regulators try to rein on misbehaviors? Which are the most active regulators on the matter?

Part 3: Natixis’ views, headways and support to prevent sustainable washing.

***

As evidenced by the recent DWS’ controversy, financial regulation and supervisors are expected to become stricter on ESG and sustainable finance washing practices. Those issues can further result in litigation and liability risks and therefore in regulatory fines, ad withdrawing or product reclassification. With consumers now expecting businesses and financial institutions to “play their part”, significant reputational and market risks are also looming. To adapt to the rapidly evolving regulatory context and thus successfully mitigating related-risks, firms’ action must be guided by authenticity, measurability and proportionality. ESG should be central to marketing and communication only when it is a real structuring and core component of a given product, portfolio selection criteria, mid to long term strategy etc.

***

FOREWORD: SEC & BaFin investigations against DWS for alleged “ESG washing”: the latest evidence of an ongoing backlash

According to an article from the Wall Street Journal (paying access) published on August 1st , 2021, Deutsche Bank’s investment arm, DWS, has inflated the ESG credentials stated in its 2020 annual report. The German asset manager, which is the second largest in Europe, claimed that ESG integration process applied to half of its $900 bn Assets under Management (AuM). Those ESG washing allegations were backed by leaked internal documents and more importantly by Desiree Fixler, the company’s former Global Head of Sustainability. She declared that she was fired after objecting to inconstancies between the company’s public statement and its ESG integration processes and policies. This is one of the first examples of whistleblowing on ESG matters.

Though allegations were “firmly rejected” by DWS in a statement to the newspaper, arguing it stood by its annual report disclosures that differentiated between “ESG Integrated AuM” and “ESG AuM”, both the American and German financial regulators – respectively the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the BaFin – began a probe. If prosecutors were to find that the fund manager exaggerated its ESG commitments, the firm could be ordered to re-label funds, offer financial compensation to misled clients for whom ESG was a key factor or condemned to fines (calculating financial prejudice is difficult).

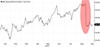

Despite the early stage of the investigations, this triggered panic on the market on August 26th. Not only DWS’s stock fell by 13.7% – the biggest decline since the coronavirus pandemic hit financial markets in March 2020 – but even the stock of its parent company fell by 2.3% at the close in Frankfurt. As of today, DWS stock still has not recovered from last month’s sharp drop.

Figure 1: The impact of ESG washing accusation on DWS' stock

Source: Bloomberg

If the controversy initially pertained to greenwashing, it is starting to raise annex yet essential questions like third party involvement. With PwC both advising DWS on its net-zero neutrality strategy while investigating greenwashing allegations, this affair may shed light on conflicts of interest despite Chinese walls. Questioning third-party’s independence is all the more relevant that they are supposed to safeguard against risks.

Part 1: Sustainable washing takes multiple forms and occurs in a wide range of industry

1. What is sustainable washing?

The concept of greenwashing first emerged in a 1986 essay written by Jay Westerveld, an environmentalist, that denounced hotels’ practices encouraging customers to reuse towels, apparently to protect the environment but rather as a mean to cut costs and improve profit margins. Now, the definition of greenwashing broadly encompasses companies that make inflated or misleading environmental claims.

With the fast-pace and wide-scale development of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Responsible Business Conduct, what applies to environment stricto sensus is also applicable to ESG as a whole ecosystem of actors, practices and products, and so under the idea of “ESG” or “sustainable washing” (see Part 2).

ESG washing could be defined as abusive marketing practices where sustainability benefits of a financial product, service or strategy are exaggerated or misrepresented, and thus possibly misleading. As opposed to a marketing strategy that would put forward a reasonable ESG argument, valuing a corporation’s sustainable approach through communication and advertisement, sustainable washing puts forward an ESG approach or benefits that are partial, unproven or inexistent. As consumers expect businesses to “play their part”, companies must differentiate and highlight their positive contribution. ESG washing is a consequence of advertisement and communication dynamics. Although there is a consensus on the concept of ESG washing, it can be difficult to agree on specific and real-life cases.

2. What forms is it taking? What are the red flags?

With 83% of consumers thinking companies should be actively shaping ESG best practices (PwC, June 2021), firms might be tempted to rush into “ESG-marketing” without developing a robust sustainable approach and safeguards. Marketing can therefore easily turn into abuse when it comes to ESG. Green and sustainable washing thus comes in 7 shades as identified in the Sins of greenwashing (TerraChoice, 2010):

- Hidden Trade-off: suggesting a product is green – or sustainable – based on a very narrow set of attributes without paying attention to other major issues;

- No-proof: green and/or sustainable claims cannot be substantiated by easily accessible and reliable information or by a third-party certification;

- Vagueness: the claim is poorly defined and/or so broad that its real meaning is likely to be misunderstood by the consumer;

- Irrelevance: the environmental/sustainable claim may be truthful but is unimportant or unhelpful for consumers seeking environmentally/sustainably preferable products;

- Less of two evil: within the product or service category, environment or sustainable claims may be true but may distract consumers from the greater environmental/sustainable impact of the category of products (e.g. organic cigarettes);

- Fibbing: the environmental/sustainable claims are simply false, which is the least frequent form of greenwashing according to TerraChoice’s report;

- Worshipping false labels: either through words or images, it gives the impression of a third-party endorsement even though such an endorsement does not exist.

In addition, a frequent misleading practice consists in using an image echoing to natural elements (e.g., water, air, nature, ocean, forest, river) to advertise a product or a service.

Sustainable washing thus commonly falls into two categories: it either relies on abusive marketing promises (the product or service is presented as fully beneficial to the environment and/or the society while the product or service is only partially or not beneficial at all to the environment and/or society), or an insufficient (or inexistent) information and argumentation (the environmental or social benefices of the approach is so insufficiently explained that it misleads consumers).

3. Are there industries prone to sustainable washing?

Green and sustainable washing do not seem to be circumscribed to one industry specifically. According to a “sweep”, a screening of website exercise carried out by the European Commission and national consumer authorities to identify breaches of EU consumer law in online markets, which focused on greenwashing in 2021, 42% of the online claims from various business sectors (e.g. garments, cosmetics, household equipment…) may be false or deceptive and could therefore potentially amount to an unfair commercial practice under the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD).

This exercise proves that a wide range of industries and businesses is inclined to use ESG abusively for marketing and public relations purposes. Among all the sectors, however, the so-called “brown industries” may be specifically inclined to inflate the benefices of their products, services or sustainable approach for marketing purposes (see our Series “Brown industries: the transition tightrope”). According to Green Initiatives, greenwashing thus commonly occurs in the food and beverage, cosmetics, electronics and household appliances, fashion, automobiles and transport industries.

In the automobile industry for example, leading firms, such as Volkswagen, BMW, Chevrolet, Ford or Mercedes-Benz, have been involved in ‘clean diesel’ cheating scandals. Compared to greenwashing practices described above (see Part III), fraud is an aggravating circumstance in green marketing. In the case of Volkswagen, which was reported cheating on clean diesel vehicles’ carbon emission tests while advertising abiding by the emissions rules, the firm said it paid €31 bn in related fines and settlements since 2015. Regarding ESG washing, Danone withdrawing health claims application on bestselling yoghurts in 2010 is a striking example of how companies may abusively rely on science for marketing purposes.

4. What are the risks associated with sustainable washing?

Companies making misleading claims on environmental or sustainable credentials could be the targets of legal actions.

On climate specifically, according to the UN Environment, Global Climate Litigation 2020 Status Report, the number of lawsuits has nearly doubled between 2017 and 2020 (from 884 to 1,550 cases). As highlighted in Natixis’ recent piece on a Dutch Court ordering Shell to reduce its emissions, thereby harbingering a climate litigation era, climate lawsuits against States and corporations started to result in historic decisions. For instance, the Constitutional Court of Karlsruhe invalidated part of the provision of the Federal Climate Change Act in Germany in 2021. In July 2021, the Conseil d’État in France has also enjoined the French government to take additional measures to achieve Paris Agreement’s objective of cutting GHG emissions by 40% below 1990 level by 2030 . The Jurisdiction observed that the reduction of GHG emissions in 2019 was slight and that the one of 2020 was not significant enough compared to the halt of the economic activity. In that regard, cutting emissions by 12% in-between 2024 and 2028, as planned by the Government, does not seem feasible to the French Supreme administrative Court without any additional measures.

If climate change lawsuits also target financial institutions to hold them accountable for the impacts of their investments, the causal link between their decisions and negative externalities is more difficult to isolate. None of the suits filed against financial actors have thus yet resulted in an exemplary conviction. However, recent actions in 2021 may be signaling a turning point in the history of climate and ESG litigation against financial actors. Despite the conclusion of Citigroup’s analysts on DWS’ case (published in client note on September 13th) struggling “to see how regulators can hold DWS to account, because sustainability requirements are subjective, making it hard to enforce, even if there was wrongdoing”, financial regulators seem willing to take an increasingly offensive stance on exaggerated sustainability claims.

Firms’ overstated sustainable commitments have led to convictions for abusive marketing. Eni, an Italian oil company was fined €5M in 2020 after running a marketing campaign that presented its palm-oil derived “Diesel Plus biofuel” as having a positive impact on the environment, without mentioning the links between palm oil and deforestation.

Green or sustainable washing can further result in huge reputational risks as consumers increasingly expect corporations to “play their part”, market risks (e.g. sizable impact on corporations’ share price), regulatory fines, ad withdrawing or product reclassification on the legal basis mentioned below.

5. What are the legal grounds suitable to sustainable washing?

The essence of sustainable washing, which finds itself at the crossroad of sustainable strategy and finance, communication and marketing, involves a large number of authorities (e.g., national jurisdictions, financial regulators, advertisement authorities). To add up to this intrinsic legal complexity, not all the applicable texts (directives, laws, doctrines, recommendations, guides…) have the same legal scope and impacts (binding or not).

Litigation risks are posed by the exposure of corporations to various stakeholders that want to hold them accountable for the negative impacts of their activities on the environment, society and governance factors. Corporations can thus be taken before Courts or independent administrative authorities, notably the ones in charge of the protection of Consumers’ rights.

Broadly speaking, liability may arise from making misleading ESG-related statements under national general consumer laws (see the table below).

Table1: Sample of consumer laws providing legal ground for greenwashing proceedings

|

Europe |

Consumer Rights Directive (2014) |

|

France |

Consumption Code (1993-1995) |

|

UK |

Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations (2008) |

|

United States |

Federal Trade Commission Act (1938), Lanham Act (1946) |

As evidenced by the publication on September 20th, 2021 of the final Guidance for businesses making environmental claims in the UK by the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), green washing is an area of interest for the Consumer Protection Authority.

|

The guidance sets out the following principles to help businesses comply with the law:

Source: Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), “Final Guidance for businesses making environmental claims” |

Alternatively, additional legal grounds to condemn green and sustainable washing practices can be found in fraudulent misrepresentation (with cases on both sides of the Atlantic, in the US with the case of DeWind v Glenmore Wind Farm, and in the UK with the Volkswagen diesel gate scandal), Contract Law (e.g. if the product is not of satisfactory quality, a breach of contract can be raised) ; and Competition Law (e.g a company claims that its products are greener than its competitors’).

On that topic, the European Union is comparatively more advanced on the topic. Various initiatives of the European Commission aim to tackle green and/or sustainable washing.

First, the European Green Deal states that “companies making ‘green claims’ should substantiate these against a standard methodology to assess their impact on the environment”. Additionally, the 2020 Circular Economy action plan commits that “the Commission will also propose that companies substantiate their environmental claims using Product and Organisation Environmental Footprint methods”.

In relation with this action plan, through the New Consumer Agenda, the EU updated the overall strategic framework of the EU Consumer policy to empower consumers for active participation in the green transition.

In the specific case of financial products, in an attempt to curb ESG washing, the European Commission advanced on the matter with the introduction of the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) which took effect last March. The SFDR sets new transparency standards by requiring all entities providing investment or insurance within the EU to classify their products. Blurred categories of products and self-labeling create confusion that the European Regulation aims at stifling. Depending on the level of ESG integration, the SFDR specifies that funds can be classified under article 8 (products that promote environmental or social characteristics), article 9 (products that have an environmental or social objective, without harming the other objective, and that use minimum governance standards) or article 6 (products that do not fall under the article 8 or 9). If the SFDR requires asset managers to document portfolios’ ESG claims, cases like the one of DWS might signal that Europe still leaves to much room for interpretation to the fund managers.

Among countries, with the introduction of a dedicated legal amendment (number 5419) to the consumer code within a review on climate change and resilience, France might be one of the most advanced nations on the issue.

Through that review of the Consumer Code, France has introduced direct sanctions against greenwashing. Guilty parties can now be fined up to 80% of the cost of the false promotional campaign and ordered to publish correction on billboards or in the media and a 30-day clarification on the company’s website.

Originally, France has also restricted the use of ‘carbon-neutrality’ in communication. Under the article 12 of France’s Climate Law, alleging that a product is “carbon-neutral” is now forbidden unless the advertiser can demonstrate it is engaged in a virtuous approach aiming primarily to avoid and reduce its GHG emissions and compensating. Emission compensation should only be used in last resort and should meet high environmental-quality standards.

To encourage actors to communicate and advertise appropriately, proportionally and responsibly, the French Autorité de la Régulation Professionnelle de la publicité (ARPP) - which oversees professional advertisement – got involved on sustainability-related issues.

|

To prevent greenwashing, every advertiser willing to use an ecological argument must submit it for approval to the Authority. In other words, every claim, indication or presentation, that links a brand, a product, a service or an action to the respect/protection of environment, whether it is central or secondary to the ad, is verified by the ARPP before distribution, in collaboration with ADEME.

The ARPP issued in 1990 and frequently reviews a “sustainable development recommendation” (2020 version). To control the content of advertising message, 9 guiding principles were set.

On the basis of this recommendation, 89% of the environmental ad projects submitted to the ARPP were modified between June and November 2020. |

Figure 2: Typology of recommendation's breaches according to the ARPP (2019)

Source : French Autorité de la Régulation Professionnelle de la publicité (ARPP),

2019 Report on Advertisement & Environment. Available here

In a way, corporate greenwashing, which consists in putting forward ESG credentials for products in practices to shape perceptions, slightly differs from financial greenwashing. The latter is rather about putting forward a “positive impact” even if the fund/product is not managed/structured in a manner that is consistent with the promotion of such an impact.

Part 2: With the boom of sustainable finance, financial actors are increasingly exposed to sustainable washing risks.

6. Focus on Green or Sustainable self-labeled financial products

As illustrated by the DWS recent controversy, the financial sector struggles to find the line between the fair promotion of ESG credentials and ESG washing.

When it comes to environment and climate specifically, pursuant to the Article 2.1 of the Paris Agreement, the financial industry must contribute to making financial flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development. Since 2015, ESG AuM have been soaring. According to Bloomberg Intelligence, they are set to exceed $50 trillion by 2025, which would surpass a third of the global total in assets under management.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has warned that a price bubble may be coalescing in the ESG market, pinpointing similarities between the rapid growth of ESG mutual funds and ETFs with the booming housing market prior to the 2008 financial crisis. According to the BIS, “there are signs that ESG asset valuations may be stretched” as evidenced by clean energy companies which continue to have price-to-earnings ratios well above “richly valued growth stocks”.

Beyond the mere rebranding of existing funds, such a boom is fortunately also fueled by real changes in investment strategies and processes that requires investors’ information and consent. However, even when ESG filters are applied, they do not always entail in significant changes in assets selection based on sustainability criteria. Criteria ponderation is limited by tracking errors constraints. On the other hand, increasing the weight of extra-financial criteria would expose actors to greater uncertainty and volatility, notably because of the flaws of ESG data.

As stated by the SEC in its risks alert released in April 2021, “this rapid growth in demand, increasing number of ESG products and services, and lack of standardized and precise ESG definitions present certain risks”. Due to the soaring demand for ESG investment – and with, in average, two new ESG funds launched everyday – ESG washing in the financial sector becomes increasingly likely. Because ESG is seen as a driver of performance (especially a beta driver when market conditions turn harsh), or a box to tick and a topic to communicate on; the more the ESG markets will grow, the more material the ESG washing risks will become.

According to a survey conducted by Quilter Investors in May 2021, greenwashing is the biggest concern for 44% of investors when investing in ESG (such expression is problematic in itself because investing in ESG can mean thousands different things), pressuring them to become “increasingly sensitive to the effects of companies that may be exaggerating their green credentials to capitalize on the growing demand for environmentally safe products”.

Asset management activities

Despite the inflation of AuM and financial products allegedly taking into account ESG criteria, objectifying the impact of ESG and sustainable finance products is actually complex for multiple reasons.

As highlighted in “Doing Good or Feeling Good? Detecting Greenwashing in Climate Investing” (August 2021), achieving portfolio improvement is attractive for marketing purposes but it is not guaranteed that it will translate into meaningful real-life impacts. Therefore, leveraging investment to drive impact in the real economy is way more ambitious than just investing companies which can boast of a positive impact.

In the case of SRI, mitigating greenwashing risks becomes even more complex as two greenwashing types overlap. There is a ‘corporate greenwashing risk’ which implies to invest in companies that practice greenwashing themselves. On the other hand, there is also a portfolio greenwashing risk that is rather about trying to make investors believe that the portfolio is green.

At the portfolio level, having an impact suggests:

- During the due diligence phases that one has the capacity to invest in ESG best performing companies. This implies that asset managers must have access to relevant yet reliable ESG data on each company and that it must be able to compare it to its sector.

- During the holding phase that one is able to enhance portfolio companies’ ESG performance. This suggests that it is not only able to measure and monitor companies’ performance but that it may have to engage with the company.

|

Focus on shareholder activism

As reminded by EDHEC Scientific Beta Research Chair, capital allocation and engagement should go together. Just like capital allocation, engagement, through dialogue with management and shareholder voting and proposals, can increase investors’ impact. Engagement is only impactful when clear signals that the dialogue will be followed by consequences in terms of portfolio decisions are sent. For instance, when an investor holds discussions with a portfolio company to get it to mitigate emissions, it would be counterproductive to increase the “weight of the company’s stock in the portfolio without relevant strings being attached”.

|

The EDHEC’ study, which focuses primarily on climate, finds that “commonly-used portfolio construction mechanisms fail to deliver consistency with impact objectives” as “the vast majority of institutional funds and mandates that claim to have a positive impact on the climate are exposed to large and obvious greenwashing risks, largely because they exhibit attractive climate metrics at portfolio level through implementation of these flawed strategies”.

It further reveals that:

- Little is accomplished to reallocate capital in direction and a manner that could incentivize companies to contribute to the climate transition.

- Often, the key feature of climate strategies is to improve portfolio greenness scores. Though the use of climate data to construct portfolios is a subject of massive communication, these data represent at most 12% of the determinants of ESG portfolio stock weights on average.

- It is easy to display greenness by underweighting heavily emitting sectors. However, in sectors like energy, which is key to achieve the decarbonation of the economy, the financing of carbon efficiency is essential.

- The portfolio’s green score is not informative of individual firm dynamics.

Investment Banking activities

Dedicated types of sustainable financing instruments emerged over the last decade to satisfy market participants’ appetite for transparency and granular asset-related impact data (e.g. social, transition, and sustainability-linked, see our July 2020 editorial “Structuring formats and thematic proliferation: orientation map”). Such instruments either have pre-determined use of proceeds, or have their financial characteristics tilted to sustainability KPI focusing on outcomes and results. These are proxy of impact and allow investors to monitor the effects (see their shortcomings in the chart below).

However, these instruments are not immune to greenwashing accusations. According for instance to S&P Global Research, “Sustainability-washing” concerns are also on the rise when it comes to sustainable financing instruments (To mitigate greenwashing concerns, transparency and consistency are key, August 2021)

Even in the case of Green Bonds, which have been around for a decade now, and despite markets’ efforts to converge towards standardization (e.g Climate Bonds Initiatives, ICMA’s Bond Principles or Guidelines), there are still divergent practices. Such industry-led initiatives have the merit to set governance and transparency guidelines, but rarely address the level of ambition and stringency regarding assets and activities eligibility. Nevertheless, the critical ambition aspect is addressed through the Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles regarding the calibration of sustainability-performance targets. However, science-based benchmarks are partially covering market participants needs in terms of sectorial and geographic coverage or usability. Moreover, only investing in aligned activities or assets could have significant capital flow eviction effect. Below, we have mapped further related-sustainable washing risks and challenges per format:

Chart: Sustainable washing risks & challenges per category of fixed-income sustainable instruments

Source: Authors (Natixis)

Mitigating green and sustainable washing risks is a complex process. In addition to the poor or discrepant definitions of “ESG”, “Environmental”, “Social”, “Governance”, “Impact Investing” and “Socially-responsible investing” labels, “responsibility” and “sustainability” are subjective.

With growing interest in environmental and corporate social responsibility issues by savers in their investment choices, labels have been introduced to specify the green, sustainable, or responsible features of financial products. In France, the government introduced the Greenfin label in 2015 (known as the TEEC - Energy and Ecological Transition for the Climate at the time) and the Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) label in 2016 for investment funds to tackle information asymmetries, avoid greenwashing risks and create a common set of rules.

The SRI label requires that ESG criteria (environmental, social and governance) be systematically and measurably integrated into investment decisions. A set of requirements are defined (by decree) on the objectives targeted by the fund, the selection process (analysis and rating methodology), the inclusion of ESG criteria in the portfolio's construction and operation, the ESG engagement policy, as well as on indicators of the impact of investments on the environment and society to be respected by candidate funds.

The Greenfin label is more restrictive than the SRI label as the investment scope is limited: more than 75% of the fund must be allocated to green bonds or green activities that are precisely defined by a taxonomy. In addition, certain sectors that are not compatible with the energy transition or controversial (nuclear, fossil fuels) are excluded. Funds benefiting from the label must have set up a mechanism to monitor ESG controversies and publish a report and indicators to measure the environmental benefits brought by the invested assets.

Other French examples of labels include the Finansol and Relance labels. Note that there is a project of European Eco-label for financial products.

Labels exist to lower transaction costs and provide reliable criteria in terms of integrity. But due to rapid market changes, labels are exposed to a credibility and relevance loss. In the case of the SRI label in France, the Inspection General des Finance (IGF), found that despite its “quantitative success” (labeled funds amount to 5,8% of the French household savings), this label “makes a confusing commitment”. Indeed, the SRI label quickly established itself thanks to its generalist and inclusive nature, but this label is increasingly exposed to greenwashing risks. Unlike the Greenfin label, the SRI label does not impose sectoral exclusions, preferring the "best in class" approach, which requires SRI funds to select the best rated companies from an extra-financial point of view within their universe. Thus, eligibility is based solely on ESG rating, which is still very heterogeneous between the different rating agencies[1]. The SRI label is also criticised because it does not guarantee that the investments in question will systematically have a measurable impact. In fact, the methods, data, and market participants do not appear to be sufficiently mature for the SRI label to be able to guarantee a measurable impact from the labelled funds.

Faced with this proliferation of labels, and therefore risks of greenwashing, several European initiatives have been undertaken at European (see our article on the SFDR) and national level.

The French financial market authority (Autorité des marchés financiers, AMF) published a doctrine in March 2020. It aims at ensuring that the information provided to investors regarding non-financial criteria is proportionate to the objective and effective impact. Funds wishing to promote the integration of extra-financial criteria as a central element of their communication will have to comply with minimum standards specified in AMF’s doctrine, namely:

1. The approach adopted is engaging. It provides measurable objectives concerning non-financial criteria

2. Non-financial criteria must have a significant impact on the objectives thus defined [2]

3. The non-financial analysis, non-financial indicator or non-financial rating coverage rate must be higher than 90%

The policy also states that collective investment undertakings (CIU) having “non-significantly engaging approaches” could mention non-financial considerations in their Key Investor Information Document investment product in “concise and balanced manner”[3].

To better tackle the new challenges that come with green and sustainable washing, financial regulators tend not only to strengthen their structures and capabilities (e.g., Germany, United States...) but also to publish guidelines or, at least, observations on the current state of affairs of ESG on financial markets.

Case study #1: The BaFin, Germany

For a while, or until recently, the primary focus of supervisors was on governance. Following the Wirecard AG insolvency scandal in Germany, financial supervision reforms have been underway to give more competencies and significantly more power of intervention.

|

Last August, the BaFin started a consultation on its guidelines on sustainability-oriented funds. Only published in German, the draft sets out the requirements that the fund managers will have to meet when labelling or explicitly marketing sustainable retail investment funds.

This guideline applies to every retail investment fund established under German Law. To include a sustainability reference in its name (e.g., “ESG”, “sustainable”, “green”) or be promoted as sustainable, including in prospectus and marketing, a retail fund must satisfy at least one of the following criteria:

|

Case-study #2: the SEC, United States

The Biden Administration made of tackling climate change a priority, liability risks might expand in the U.S.

Last March, the SEC thus formed a task force dedicated to investigating companies’ potential misconduct when it comes to sustainability claims.

|

The SEC later issued in April a “Risk Alert” and pointed out “observations of deficiencies and internal control weaknesses from examinations of investment advisers and funds regarding ESG investing”.

Regarding ESG investing processes and representations, the staff noted potentially misleading statements. “Despite claims to have formal processes in place for ESG investing; policies and procedures that did not appear to be reasonably designed to prevent violations of law, or that were not implemented; documentation of ESG-related investment decisions that was weak or unclear; and compliance programs that did not appear to be reasonably designed to guard against inaccurate ESG-related disclosures and marketing materials.”

The SEC observed that: 1. Portfolio Management practices are inconsistent with disclosures about ESG approaches; 2. Controls are inadequate to maintain, monitor and update clients’ ESG related investing guidelines, mandates and restrictions; 3. Proxy-voting are inconsistent, with discrepancies between public ESG-related proxy voting claims and internal voting policies and practices; 4. ESG approaches are unsubstantiated or otherwise potentially misleading; 5. The controls to ensure that ESG-related disclosures and marketing are consistent with the firm’s practices are inadequate; 6. The compliance programs are not adequately addressing relevant ESG issues and are less effective when compliance personnel had limited knowledge on ESG.

The SEC also highlighted some effective practices with investment advisers and funds having in place: 1. “Disclosures that accurately conveyed material aspect of the firms’ approaches to ESG investing”, they were “clear, precise and tailored to firms’ specific approaches to ESG investing, and which aligned with the firms’ actual practices”; 2. “Policies and procedures that addressed ESG investing and covered key aspects of the firms’ relevant practices (...) with detailed investment policies and procedures that addresses ESG investing”; 3. “Compliance personnel that are knowledgeable about the firms’ specific ESG-related practices”.

The SEC said it would “continue to examine firms to evaluate whether they are accurately disclosing their ESG investing approaches and have adopted and implemented policies, procedures and practices that accord in their ESG-related disclosures”. Further examinations will include:

On September 22nd, the SEC released a sample letter to companies as “a number of its disclosure rules may require disclosure related to climate change”. The American regulator is getting more specific about what companies should integrate about climate change in their annual financial reports. Though the list of questions is not exhaustive and will be tailored to specific companies and industries, the SEC signals that information on climate-change related risks and opportunities may be required in the corporate description of business, legal proceedings, risk factors, and management’s discussion and analysis of financial condition and results of operations. |

Case-study #3: the AMF, France

|

Due to the increasing number of references to ESG themes in financial communication, the French Market Authority (AMF) published in March 2020 on the information that must be provided for collective investment schemes integrating an extra-financial approach. To prevent the risks of ESG washing, the AMF’s position, which is applicable to collective investment schemes managed and distributed in France to non-professional investors, distinguishes three distinct levels of ESG integration approaches: i) significantly committing approaches, ii) non-significantly committing approaches, iii) other approaches that do not meet the standards applicable to central/restrained communication.

The AMF further applies:

|

Figure 3: Overview of AMF’s position on the information to be provided by collective investment schemes incorporating non-financial approaches

Source: Natixis

To be used as a central element of communication, the products should meet minimal standards.

To mention centrally “SRI”, “ESG integration”, “responsible”, “sustainable”, “green”, “ethical”, “social’, “impact”, “low carbon” etc. in the name of the product, the key information document or the commercial documentation, the approach should be based on a commitment, with regulatory documents mentioning planned measurable targets integrating ESG criteria.

This commitment must be significant and thereby relying on one of the following approaches:

- “Improvement of rating” compared to the investable universe: the fund’s rating must be superior to the investment universe rating after the elimination of 20% of the lowest-rated values;

- An approach based on “selectivity”: reduction of at least 20% of the investment universe);

- An approach based on the “improvement of extra-financial indicators compared to the investable universe”; or,

- Any other approach that will allow asset managers to prove the AMF that its approach is significant.

For significant commitment-based approach, a minimum of 90% of the assets must be provided with extra-financial ratings and analysis.

|

The AMF provides examples of criteria on what is required to be allowed to mention ESG in the Fund’s name and with expanded developments in the commercial documents: A fund of fund which will allocate 90% of its investment to SRI funds ;

Approaches that are deemed by the AMF insufficient to represent a significant commitment include exclusion filter that only:

|

AMF’s view on fixed-income products

In the specific case of green, social and sustainability bonds, the AMF is not voluble (recommendation n°4). It only recommends inserting in the key information document an explanation of the criteria that must be respected to select green or social bonds, notably by mentioning the asset manager’s position on issuers’ application of widespread standards like the Green Bonds Principles, the Social Bonds Principles or the future EU Green Bond Standard.

Part 3: Natixis’ views, headways and support to prevent sustainable washing

Mitigating green and sustainable washing risks will be challenging yet essential for businesses to avoid further legal, reputational and market impacts.

As a substitute or complement to labels, which currently fail to act as a market signal, multi-stakeholders’ initiatives are surfacing in sustainable finance and creating soft law norms that are voluntary (self-regulation). Governing rules or principles emerge, one example being for instance the Science-Based Target Initiative (SBTi). The current lack of definition for what makes a product or an approach sustainable or green encourages financial regulators to increasingly step-in. As studied above, some of them have started issuing “risk alerts”, “guidelines” or consultation, thereby indicating to the industry, regulators’ increased scrutiny.

In the field of sustainable finance, guidelines and standards are the bedrock of product design and market integrity. Market participants need anchoring definitions and undisputed criteria. Under the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) or the Loan Market Association, set of guidelines or principles have been created (related to Green, Social, Sustainable, Sustainability-linked Loans or Bonds). Although being “soft-law” guidance, they have proved useful and inspire regulators. Most of the green or sustainable washing cases arise from self-labeling products or initiatives. Note that this phase of innovation and rule-of-thumb at the initiative of market participants was necessary and useful. The involvement of third verification parties aims at mitigating these risks. However, their independence (e.g. they are paid for by issuers in the case of GSS bonds for instance) or technical expertise have led to some complacent and lenient external reviews. This is the reason why the European Supervisors intend to create an accreditation system with far more demanding requirements weighting on verifiers. An evolution that we support.

Self-regulation from market participants, while unavoidable at the creation of a market where innovation is crucial, is fraught with risks. Greenwashing can be prevented through the development and use of taxonomies that identify specific economic activities (based on economic nomenclatures), technologies or set of conditions (performance improvement against a baseline).

Efforts to publish impact reporting can also help detecting low integrity products and weak approaches. Indeed, to be able to provide relevant impact metrics requires to clearly identify the expected benefits of a given green or sustainable finance instrument (so-called theory of change in “impact investing”). Without underlying data, measurement or assessment of the outcomes achieved through the product or financing, there is nothing to report on. Such absence should be a warning signal.

Another key aspect is to avoid assessing greenwashing only on a single product-basis. Walking the talk is essential for financial institutions. A specific index or transaction can always deviate from the integrity safeguards and redlines set by a financial institution. Sustainable finance washing should be assessed at a consolidated level. It requires evaluating consistency across the different products and business lines of a financial institution, and so throughout its various operations and activities. A mother company’s ESG or climate-related commitments must be underpinned by its own operations. For instance, the lending policies of a bank and its balance sheet related activities must not be discrepant from its financing activities (e.g. bonds underwriting). It is a matter of perimeters and scopes. For an asset manager, there must be consistency between its third-party asset management business and its proprietary asset management.

Taxonomies development, disclosure obligations and use, green or sustainable washing prevention and impact reporting are closely interrelated and must be pursued altogether.

More broadly speaking, it is essential to present the key features of a financial product, the sustainability objectives pursued through it, the rationale behind the methodology, but also the data entry points. What is critical is to avoid misleading the end-customer, investor or saver. To ensure the transparency duty, communication and marketing must only convey marketing that will not distort the reality behind products and/or services.

While waiting for policymakers and independent authorities to decide on political objectives and regulations, the best antidote against greenwashing controversies lies in responsible marketing practices, comparability and robust independent external verification (which is identified as a key topic in the EU Social Taxonomy Draft, see our article here). To get it started, market participants must:

1. Be familiar with the applicable legal grounds and the regulator’s recommendations

2. Make sure that the ESG methodology is robust enough to substantiate ESG credentials

3. Communicate and market responsibly to enhance transparency. As suggested by the AMF and the French law (e.g. on carbon neutrality). Great attention should be paid to:

- The name of the product which could easily mislead end customers: use an ESG denomination in the name of the product only if the ESG approach is central to the one of the products.

- The classification and information of products: make sure that the amount of ESG references in the marketing and communication materials is proportional to the ESG approach.

- The overall vocabulary: avoid overclaims about positive impacts, specifically when you are not able to demonstrate how your activities translate in impact, and refrain from using certain expressions such as “carbon neutrality” which is now regulated by the French law.

Figure 4: Avoiding sustainable washing and mitigating related risks

Source: Natixis

Sources:

[1] On this point, the French and Dutch financial market authorities, as well as the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) are calling for legislative action on ESG ratings and assessment tools. See article of the AMF here and ESMA here.

[2] For the best-in-class approaches for example, quantitative thresholds derived from the French SRI label will be used as a reference to judge whether the commitment is significant. For example, "selectivity" approaches will have to commit to a minimum reduction of 20% of issuers with the lowest ESG rating in the investment universe. For other approaches, asset management companies should be able to prove to the regulator in what way the commitment chosen is significant. See more information on p.6 of the policy here.

[3] Communications on extra-financial criteria in commercial documents shall be concise when they are: (i) secondary to the presentation of product characteristics both in terms of breadth and positioning in the document ; (ii) neutral ; (iii) limited to less than 10% of the volume occupied by the presentation of the product's investment strategy. See more information on page 5 of the policy, here.