IEA’s NZE scenario: is this the moment of truth for the energy sector

6-minutes read

Last week was marked by the publication by the International Energy Agency (IEA) of its net zero emissions (NZE) scenario for 2050, with some of the findings, such as the fact it sees no need for investment in new fossil fuel supply, having elicited reactions from a good number of observers. The IEA warns about the gap between rhetoric (proliferation of net-zero emissions pledges) and the action required to close. Based on the assumption of a global environment characterized by a doubling of GDP and a 2 billion increase in the population by 2050, the IEA scenario sets out a potential pathway to net zero emissions over this horizon, with the objective to limit the global warming to +1.5°C in 2100 compared with pre-industrial levels.

In this respect, the IEA does not merely describe the way in which fossil fuels (still dominant in meeting final energy needs to this day) could largely be replaced by alternative energy sources (cutting dependence on fossil fuels to 20% by 2050 from 80% currently). It also sets out the possible structure of the key pillars for the decarbonization of the global economy as currently identified in order to achieve carbon neutrality, namely:

- The direct use of low carbon electricity, essentially renewable energy sources (90% of electricity production by 2050) in various areas of activity such as the mobility and building sectors. In this respect, demand for electricity is expected to be multiplied by 2.5x by 2050, not just to directly ensure the decarbonization of the economy, but also to produce green hydrogen (20% of electricity production in 2050).

- An acceleration of improvements in energy efficiency. In particular, the NZE scenario factors in an improvement in the annual rate of energy intensity of 4% by 2030 compared with the 1% annual rate achieved on average over the past two decades.

- The development of low carbon energy sources such as biomethane, blue/green hydrogen and bioenergies. These low carbon energy sources alone are expected to meet 20% of global energy demand in 2050 compared with 1% currently.

- The large-scale rollout of carbon capture use & sequestration (CCUS) processes. The NZE scenario assumes that 3.5Gt of carbon emissions will be captured from fossil fuels by 2050, or around 10% of current total volumes, through the near systematic use of CCUS processes at industrial plants and power plants using fossil fuels.

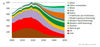

Chart 1. IEA’s NZE scenario: total energy supply in In Exajoules

Source: IEA (2021)

Meanwhile the IEA goes further, the NZE scenario describing very precisely:

(i) The intermediate phases required to achieve this scenario, notably the development of the above pillars needed for the energy transition by 2030 and the progress expected in the decarbonization of the different sectors of the economy (industry, transport, building, etc.) to achieve climate neutrality by 2050;

(ii) The size of the investment in the energy sector, with annual average spending needing to be increased from $2.3trn in the past five years to $4.5trn out to 2050. In this respect, what stands out is the extent of the spending needed in renewable energies (annual spending of $1.3trn a year on average by 2030) and in associated infrastructure (electricity networks, charging station for electric vehicles, reloading stations for hydrogen powered vehicles, etc.) enabling recourse to low carbon energy sources (for which annual spending is expected to increase from $290bn in 2020 to $880bn in 2030). Also of note is the orientation of investments in the post-2030 energy sector predominantly towards end-use (decentralized renewables, energy efficiency, hydrogen, CCUS and electrification), such trends being underpinned by behavioral changes (see below);

(iii) The nature of the underlying technological changes (near total reliance on electric batteries and hydrogen fuel cells in land transport, transition to commercial scale use of CCUS process, qualitative leap in the development of energy efficient processes and materials, etc.) and behavioral changes (personal consumption habits needing to adapt increasingly to the climate challenges);

(iv) An outline of the public policies needed in order to encourage and accompany the changes in the energy/economic paradigm underpinning the achievement of the NZE scenario. In particular, this scenario integrates the worldwide adoption of public mechanisms for pricing carbon emissions, the assumption being that this cost will reach $250/t in 2050 in advanced economies ($75/t in 2025 under this same scenario); the NZE scenario also relies on “command-and-control” policies and on drastic behavioural changes. A final 8% of emissions reductions stem from them and materials efficiency gains that reduce energy demand (e.g. flying less for business purposes).

Chart 2. Role of technology and behavioural change in emissions reductions in the NZE

Source: IEA (2021)

Such foray of behavioral changes in IEA’s scenario design is a novelty. Different types of such changes are presented, including reducing excessive or wasteful energy use (e.g. by reducing indoor temperature settings, adopting energy saving practices in homes and limiting driving speeds on motorways to 100 kilometres per hour) and transport mode switching (shift to cycling, walking, ridesharing or takin buses for trips in cities that would otherwise be made by car, as well as replacing regional air travel by high‐speed rail in regions where this is feasible).

(v) The economic and social implications of the sweeping transformation of the global energy sector, notably the net job destructions/creations in the different sectors affected by this acceleration of the energy transition process. In this respect, by 2030, the IEA expects 9 million net job creations in the energy sector, with job destructions for fossil fuel energies (-5 million) more than offset by job creations in low carbon energies (+14 million). However, the topic of fair transition is not circumvented as the IEA pinpoints that “It is paramount to remain aware that not every worker in the fossil fuel industry can ease into a clean energy job”. It accordingly advises governments to promote training and devote resources to facilitating new opportunities (see our recent article on Fair transition).

Unsurprisingly, it is the extent of the changes specific to fossil fuels contained in the scenario that has attracted the attention of observers. Note that for the first time through this report, the IEA has combined the models of its two flagship series, the World Energy Outlook and Energy Technology Perspectives. In this respect, of all the energy scenarios developed to date by the IEA, the NZE scenario is the most maximalist in terms of compliance with the Paris agreements (the 1.5°C objective being the most ambitious formulated within this framework). Indeed, the IEA had previously defined a scenario associated with a 50% chance of limiting the rise in temperatures to +1.65 ° C, the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS). This scenario was itself based on an intermediate decarbonization target (shift to overall CO2 emissions of 26.6 Gt by 2030 and 10 Gt by 2050 vs. 33 Gt in 2020) and had been built under the assumption of a massive deployment of processes allowing massive negative emissions after 2070. In the World Energy Outlook of 2020 published last October, the IEA continued its modeling work by withdrawing this assumption, which led it to design a more aggressive decarbonization trajectory by 2030 to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. This is the underlying logic of the NZE scenario which in its version published in October details a potential path towards a much lower total level of CO2 emissions by 2030 (20 Gt vs. 26.7 Gt in the SDS). The version published last week extends the sketched trajectory until 2050.

It was therefore inevitable that the implications of the NZE scenario would be the most severe for oil, natural gas and coal. For these three fossil fuels, the NZE scenario assumes a contraction in demand of 75%, 55% and 90% respectively, by 2050. This modelled contraction in demand leads the IEA to consider as unnecessary the development of new projects other than those already approved. Moreover, the downtrend in prices (oil landing at $35/bbl by 2030 and $25/bbl by 2050 in the NZE scenario) which will inevitably follow that of demand should not be without effect on the structure of supply either. It should thus lead to a concentration of world production in the countries/areas with the lowest marginal extraction costs: Middle East for oil, Russia and the Middle East for gas, etc. The United States would be the big loser in the exploitation of shale oil, given the much higher exploitation costs for shale oil ($45bbl-$50bbl) than for crude oil in the Middle East (less than $30/bbl). Their position in the gas market would be uncertain, as gas extraction in the US is now largely tied to oil extraction.

The significance of this latest IEA publication needs be put into perspective. The NZE scenario is less predictive than prescriptive in nature. It seeks less to discern the possible contours of the global energy scene 30 years from now than to quantify the extent of the transformations needed in the energy sector and other sectors of activity to limit the effects of climate change as much as possible by 2100. It reportedly strikes a balance between technical feasibility, cost-effectiveness and social acceptability. Furthermore, the scenario is based on a series of assumptions whose validity is difficult to establish under current conditions: will the brakes on scaling up CCS be lifted? Will we see major behavioral changes such as the massive development of energy for own use via the integration of solar technology into buildings and the virtual disappearance of internal combustion engines (ICE) in the passenger car market by 2035? At this stage, there is no way of telling. Apart from technological breakthrough uncertainty, the social acceptability of several contemplated measures is hardly foreseeable. The IEA acknowledges that “many of these types of behavioural changes would represent a break in familiar or habitual ways of life and as such would require a degree of public acceptance and even enthusiasm”.

One of the greatest merits of such report is that it sets out milestones (reportedly more than 400 in total) and it does so “universally” as they span across almost all sectors and technologies.

On the other hand, it is highly likely that the role assigned to fossil fuels in the IEA scenario (including gas, whose "transitional" nature can be demonstrated under certain conditions - see our report “Is green in the pipe ? Sensing natural gas’ potential contribution to climate change mitigation”) will lead to a ratcheting up of exclusion policies among institutional investors (asset managers and insurers) and lenders alike.