Covid-19 crisis in Europe: a midwife for a federalist green & social leap forward

A new chapter of history textbooks is being written in Europe and the pen could be green and social. The once politically inconceivable measures could become a reality. Taboos fall one after another[1].

For example, prior to the crisis, the European Central Bank (ECB) used to purchase government bonds in proportion to the capital each Member State contributes[2]. However, its €750bn Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP) is more flexible, allowing for instance, the purchase of more Italian and Spanish Bonds to prevent the widening of spreads. Issuer-limit that forbids the ECB from holding more than a third of any member’s sovereign debt has also been lifted. This pandemic has convinced Germany to slaughter another sacred cow...

TABLE OF CONTENTS OF THIS FOCUS ON EUROPE'S RECOVERY PLAN

- WHY IT MATTERS FOR SUSTAINABLE FINANCE MARKET PARTICIPANTS

- FINANCING THE RECOVERY PLAN

- DISCLAIMER: THIS BREAKTHROUGH PROPOSAL IS NOT YET APPROVED

- “NEXT GENERATION EU”

- A TWO-LEG ESG PROFILE WITH RESSOURCES AND EXPENSES IN SYNCH

- THE RECIPE TO BREAK TABOOS: THEMATIC, EARMARKED, ADDITIONAL AND TEMPORARY SPENDING

- DISTRIBUTING FUNDS TO MOST HIT REGIONS & SECTORS: CRITERIA INTRICACIES

- WHAT’S NEXT?

The Franco-German tandem impetus

Another taboo has been broken. On May 18th 2020, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the French President Emmanuel Macron unveiled an ambitious post-Covid EU Recovery Plan. Their roadmap is underpinned by budget solidarity through a series of subsidy-based schemes (i.e. non-repayable support different from loans). It will be financed thanks to new resources and through issuance of several hundred billion Euros debt from the European Commission on behalf of the EU. Priorities are:

- Boosting EU’s health-care capabilities;

- Strengthening its economic “sovereignty”/ strategic autonomy;

- Supporting the ecological transition.

At the heart of their proposed blueprint was a Recovery Fund worth €500bn (3.6% of the EU’s GDP), poised to be financed by common borrowing within the EU’s seven-year budget.

The European Commission's proposal for a major recovery plan

On May 27th European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen, outbid their proposal by calling for the power to borrow €750 bn to bankroll recovery efforts (retaking the €500bn Franco-German proposal and adding another €250bn in the form of loans to Member States). The debt will be repaid throughout future EU budgets – not before 2028 and not after 2058. In the same bucket, the European Commission President von der Leyen proposed new own resources to strengthen EU’s fiscal capacities[3] that rely extensively on tax basis with high ESG content (e.g. carbon and/or “GAFAM tax”, see infra). Overall, the European Commission proposed a combined €1.85 trillion of spending over 2020-2027, at least 25% of which must be ‘green’ and 100% “must do no harm”.

Table 1: EU’s proposal for a large green & social recovery plan is embedded into its long-term budget

Source: European Commission & Author

All encompassed, the proposals would have the potential to change the very status of the European Union if accepted by all Member States in this form. With increased borrowing and fiscal capacities to serve shared political priorities, we have never been any closer to a federal union.

“Our investment in rebuilding comes at a price: rising debt” stated President von der Leyen. In her speech before the European Parliament she asserted: “If it is necessary to increase our debt, which our children will then inherit, then at the very least, we must use that money to invest in their future, by addressing climate change, reducing the climate impact and not adding to it. As we come out of the crisis, we must not fall into old habits, we must not hold onto yesterday's economy as we rebuild.”

For decades, calls for Eurobonds[4] have been unsuccessful. It took the largest economic and sanitary crisis ever in peace time to open the financial orthodoxy padlock. However, governments’ liabilities would still be limited to guarantees equivalent to their contribution to the Multi-Financial Framework (MFF), but countries that receive the funds channeled to regions and sectors in distress do not need to repay them (these would indeed be grants).

Implementation details are yet to be spelt out and a final political agreement has not been forged [5], but we think such proposals will be considered as a CECA[6] equivalent in the chapters about European integration of history textbooks.

1. WHY IT MATTERS FOR SUSTAINABLE FINANCE MARKET PARTICIPANTS

With this unprecedented context in mind, we Natixis GSH decided to comment on the main aspects of this Recovery Plan because we believe it will reshape Europe institutionally and economically with significant spillover effect on sustainable finance. Common political priorities without budgetary means are toothless, but now there would be an unprecedented budgetary firepower and spending could be incurred according to principles that are core to sustainable finance products.

Private and public sectors’ progress are often in synch when it comes to sustainable finance. SSAs have for instance led the way for green bonds. We expect themes like economic sovereignty to percolate further into companies’ strategies with dedicated investment plans and associated funding needs and instruments. There will be targeted support for projects of European strategic interest for internal market supply chains to develop the EU’s strategic autonomy in key sectors and capacities. If appropriately designed and successfully implemented, the eligibility criteria for EU’s recovery interventions may also inspire the sustainable funding programs of other SSAs (e.g. agencies, public development banks) and companies. At the very least, companies will be impacted by the new taxes that will be introduced, leading some of them to improve their sustainability footprint and change their practices (e.g. supply chains, decarbonization pace, etc.).

2. FINANCING THE RECOVERY PLAN

To finance the aforementioned investments, the Commission would issue bonds (up to €750bn) on financial markets on behalf of the EU. It has issued debt before but on a much smaller scale (cumulative issues reached a peak of €271bn in 2019).

To make borrowing possible, the Commission will amend the Own Resources Decision[7] and increase the headroom that fixes the maximum amount of money that the Commission can borrow on the capital markets with the guarantee of the Member States. It consists in the difference between the Own Resources[8] ceiling of the long-term budget (the maximum amount of funds that the Union can request from Member States to finance its expenditure) and the actual spending.

On this basis, the Commission would raise funds on the markets and channel them via Next Generation EU to dedicated programs, some already existing while other programs would be created. This additional funding will be repaid over a long period of time throughout future EU budgets – not before 2028 and not after 2058.

The bulk of the €750 bn borrowing will be concentrated in the period 2020-2024 to:

- Channel the funds to one of the new or reinforced programs or finance the grant component of the Recovery and Resilience Facility

- Lend the money to Member States in need under the new Recovery and Resilience Facility based on the terms of the original emission (same coupon, maturity and for the same nominal amount). In this way, Member States will indirectly borrow under very good conditions, benefitting from the EU’s high credit rating and relatively low borrowing rates compared to several Member States.

An indicator of impact proposed is savings per Member States through recourse to EU back-to-back loans compared to self-financing on international markets.

3. DISCLAIMER: THIS BREAKTHROUGH PROPOSAL IS NOT YET APPROVED

Before delving into the specifics, please note that what is described here is still a proposal and must be politically approved, including by some national parliaments. Nevertheless, the agreement between France and Germany is a stepping stone that provides minimum certainty about the likelihood of this package being pushed forward. Ironically, the Brexit probably made this U-turn possible.

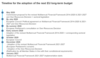

The discussed proposal fits into the multiannual financial framework (MFF), which is the EU's long-term budget. Ms. Von der Leyen proposal kicks off fierce negotiations among the EU’s 27 governments, all of which must approve the new budget. Some have already signaled displeasure. Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, the “frugal four”, want a smaller fund for loans rather than grants, and tight conditions (economic reforms and budget oversight[9]). They will also negotiate to get further “rebates”[10]. Each EU member holds a veto right in the negotiations (see the timeline of adoption below).

Source: European Commission (2020)

Ms. von der Leyen’s proposal is named “Next Generation EU” and explicitly targets regions that are suffering the most from the havoc wreaked by the coronavirus. With a budget of €750bn for Next Generation EU as well as targeted reinforcements to the long-term EU budget for 2021-2027, the total financial firepower of the EU budget would be €1.85 trillion.

The Recovery Fund will include expenses (i.e. subsidies/grants not loans) in EU member countries:

- Regardless of their financial contribution to the EU (setting aside the paralyzing debate about net contributor / beneficiary to the EU budget, thereby paving the way to budgetary solidarity)

- Based on geographical and sectorial needs: i.e. allocated to sectors and locations that have been hit the most by the current crisis. Italy, Spain and France are likely to be the leading recipients of grants. Ms. Von der Leyen declared that we need to support those that need it the most (“those parts of the Union that have been most affected and where resilience needs are the greatest”). She mentioned regions with economies that are built on client facing services – such as tourism or culture[11].

Further political integration requires an unprecedented political shock but also a consensus on the areas of intervention. One highlights that the areas of intervention echo topics of growing interest in sustainable finance (digitization is a bit less direct but with high consequences in terms of employment and social inclusion):

- Ecological transition

- Health capacities

- Economic sovereignty (reshoring of sectors, reshuffling and shortening of supply chains)

The fourth area is budget solidarity, which is more a mechanism or a logic than a proper intervention area. We are not certain whether the subsidies from the Recovery Funds will necessarily have to target at least two of the areas. One wonders for instance whether subsidies to support strategic autonomy will be assorted with a string of social or environmental conditions (e.g. ban on layoffs, commitments to repatriate in Europe parts of their tax basis should they have outsourced for optimization purposes).

For the EU4Health program for instance, the Commission says it will ensure the strategic procurement for items such as biocides (disinfectants), reagents for testing, protective gear, essential medicines, medical equipment, diagnostic reagents (e.g. breathing support, CT scanners) and other relevant goods (such as injection material and sterile bandaging). The program will also provide incentives for vaccines development, production and deployment within the Union and to relaunch EU production of medicines and active pharmaceutical ingredients/precursors.

The table below proposes an overview of the different schemes.

Table 2: Recovery plan for Europe: invest in a green, digital and resilient Europe

Sources: EU Commission

5. A TWO-LEG ESG PROFILE WITH RESSOURCES AND EXPENSES IN SYNCH

Green & social expenses

The European Commission will lend proceeds to EU countries under the Recovery and Resilience Facility to finance their reform and resilience plans in line with the objectives identified in the European Semester, including the Green and Digital transformation, the Member States’ national energy and climate plans, as well as with the Just Transition plans.

Synergies with Ms. Ursula Von der Leyen’s Green Deal are expected to play in full. As a reminder, the Green Deal includes a 50-55% emissions reduction target for 2030; a climate law to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. German Chancellor emphasizes this articulation (Germany has adopted in the meantime a very ambitious and green recovery plan[12], which noticeably excludes combustion-engine vehicles from the stimulus package).

Priorities areas of the European Green Deal are presented as the engine of the EU’s recovery strategy with emphasis on:

- A massive renovation wave of buildings (to double the renovation rate in building) and infrastructure and a more circular economy, bringing local jobs;

- Rolling out renewable energy projects, especially wind, solar and kick-starting a clean hydrogen economy in Europe;

- Cleaner transport and logistics, including the installation of one million charging points for electric vehicles and a boost for rail travel and clean mobility;

- Strengthening the Just Transition Fund (worth €100bn) to support re-skilling, helping businesses create new economic opportunities

The table below presents an overview of the EU’s sustainable development agenda.

Table 3: Sustainable development European policy objectives and initiatives

Source: European Commission

Another priority is strategic autonomy which displays several environmental and social benefits (in terms of GHG emission avoidance from transportation or local jobs creation, with however downsides in terms of goods affordability for customers). For resilience, the objective is to build stronger European value chains in line the New Industrial Strategy for Europe[13], as well as supporting activities in critical infrastructure and technologies. Among the “schemes”, one highlights the new Strategic Investment Facility that is to be created to invest in key value chains crucial for Europe’s future resilience and strategic autonomy, such as the pharmaceutical sector. President von der Leyen argues that “Europe must be able to produce critical medicines itself”. This will help match the recapitalization needs of companies who have been put at risk as a result of the lockdown – “wherever they are located in Europe”, she insisted. Germany is reportedly reluctant to include capital stakes in the perimeter of eligible spending. Tomorrow, the EU could become an active shareholder in strategic sectors by acquiring stakes in companies meant to become European champions[14].

We believe that the current situation could also convince decision-makers to accelerate efforts in defining an EU social taxonomy of economic activities, with contribution to health as first objectives with technical screening criteria (with this regards, the 2030 Agenda and European Commission’s previous work on the SDGs might be useful[15]).

On the social angle, the European Commission proposes a supposedly fair and inclusive recovery, including:

- The short-term European Unemployment Reinsurance Scheme (SURE) will provide €100bn to support workers and businesses;

- A Skills Agenda for Europe and a Digital Education Action Plan will ensure digital skills for all EU citizens;

- Fair minimum wages and binding pay transparency measures will help vulnerable workers, particularly women;

- The European Commission is stepping up the fight against tax evasion and this will help Member States generate revenue.

On the Just Transition Fund, a study by Policy Department for Budgetary Affairs has just been released[16].

Green & social resources

To facilitate the repayment of the capital raised on the financial markets and further help to reduce the pressure on national budgets, the Commission will propose additional new own resources at a later stage of the 2021-2027 financial period. Brussels reportedly aims at new taxes and levies that could cover all interest and repayment costs.

Subject to political vote, we ignore what revenues will be affected to this Recovery Fund. Most of the proposals relate to ESG issues (e.g. carbon taxation, we think a levy on air traffic is unlikely considering the state of decay of the industry, one on maritime transportation is more likely as it could “relatively” disadvantages imports from outside Europe with some ecological ground). President Ursula von der Leyen wants to expand the ETS to include emissions from transport, shipping and heating buildings, to increase its coverage to over 90% of emissions. But that brings up the issue of trade. A digital tax on platform giants is also on the table. Tax on non-recycled plastic waste proposed last February (with potential income of €7 bn a year) is also mentioned. The most powerful and credible option is a levy on carbon-intensive industrial products shipped from outside the EU, but it could reignite trade war with action through the WTO. Such a “border carbon adjustment” mechanism is a tariff imposed on imports from countries which are not members of the carbon-pricing scheme. It allows schemes to “reach” and price emissions otherwise hidden: those “embedded” in imported goods and to level the playing field. The only existing example is in California[17].

Table 4: Possible additional “own resources” considered by the European Commission for the 2021-2027 financial period

Source: European Commission (2020)

6. THE RECIPE TO BREAK TABOOS: THEMATIC, EARMARKED, ADDITIONAL AND TEMPORARY SPENDING

The decade-long refusal to any European debt mutualization could possibly be overcome by introducing three specific features in the envisioned Fund:

- Specific & thematic with ring-fencing of the funds towards health, economic sovereignty, ecological transition

- New expenditures adopted after the pandemic outbreak (refinancing seems excluded, but in most countries, budget planning is multi-annual)

- Temporary: meaning the Recovery Fund is meant to be phased out and should last only for the timeframe of the crisis. Next Generation EU plan is to raise money by temporarily lifting the own resources ceiling to 2.00% of EU Gross National Income, allowing the Commission to use its strong credit rating to borrow €750bn on the financial markets.

A new European Public Prosecutor’s Office[18] will investigate any misuse of funds. Investments and reforms that will benefit from financial contributions under the Recovery and Resilience Facility will be identified in the context of the European Semester, thereby ensuring additionality and facilitating the monitoring of their implementation. These features appeared as pre-requisite for political consensus and it was also the case for the European Stability Mechanism’s brand-new program (without economic reforms, only use for health expenditures in response to the pandemic). One notices that they also reflect investors’ view on covid-19 response and so-called pandemic financing instruments (contact us to get the results of our investor survey).

Such features echo the content of a letter signed by 109 investors calling for a green recovery in Europe (investors totaling €11.9 trillion in AuM or advice)[19]. They encourage European leaders to ensure that at least a 25% climate-mainstreaming ambition is maintained as part of the Multiannual Financial Framework for 2021-2027 (MFF). In particular, investors state that carbon intensive companies that receive government bailouts, grants, loans, tax concessions and temporary equity purchases should be required to establish and enact climate change transition plans consistent with the Green Deal and Paris Agreement goals, and to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 in exchange for this public support.

Extra public indebtedness seems acceptable by deficit-phobic countries and Maastricht-like rules defenders but also by financial community when it is ring-fenced (answering the question: where does the money go?), sufficiently granular, presented as time-bound or at least temporary (i.e. that it does not lead to structural and irreversible expenditures, that are scrutinized by credit rating agencies). Note that this temporary feature does not mean that the three areas are short-lived priorities only that the ad hoc scheme is.

Still, we believe that because of hysteresis effects (remnant effects), the temporary feature may be reconsidered. If the Recover Fund reveals successful, it might be repurposed and, in the end, never dismantled, especially because the European Parliament will be involved as the overall plans fit within the EU’s seven-year budget.

7. DISTRIBUTING FUNDS TO MOST HIT REGIONS & SECTORS: CRITERIA INTRICACIES

As always, simplicity and criteria systematism are necessary for programs reportedly aiming at targeting vulnerable or disadvantaged populations or economic sectors. On what criteria and basis money will be distributed is the critical question; some refinement is possible with this need for simplicity in mind. As often, when a new topic is tackled it requires innovation that lies in eligibility criteria or methodology. As it is for sustainable finance, such innovation is inherently limited by the shortage of usable and reliable data. We believe that the EU Recovery plan can unleash a new wave of methodological innovation in green & sustainable finance and lead to emergence of new types of financial instruments in this category. The eligibility criteria can be used to demonstrate the investment rationale from sustainability standpoint. More importantly still, given that missing or unreliable data have long been one of the limiting factors for the development of sustainable finance, these criteria can over time lead to a creation of available data of better quality and scope.

Expenses should be mainly subsidies from the EU Budget, but money would be channeled through national entities, Banque Publique d’Investissement in France, for instance. We do not imagine direct funding from the EU to national companies or local governments, with a total bypassing of national entities. EU members may be in charge of reviewing and filtering the requests.

The three criteria considered by the European Commission for the schemes aiming at supporting the regions and sectors that suffer the most from the pandemic – country’ GDP; GDP per capita; average unemployment rate between 2015 and 2019 - have been rightly criticized[20] by several Member states as ill-designed. It is true they reveal a gap with the stated intention and might fail in the effective targeting of most hit countries. According to the formula, Belgium which had suffered acutely would receive very little. The political challenge is that the pandemic has dire consequences in southern Europe whereas Eastern Europe countries, which usually are the largest beneficiaries of EU Aid, have been relatively unscathed.

In the same vein, there is a risk that recovery plans lead to further imports from outside Europe, especially if based on household’s consumption[21]. Possible mitigants are to prioritize goods and services produced domestically in extra spending programs, to introduce a CO2 tax at the EU border and try to rapidly reshore the production necessary to meet the extra demand arising from recovery plans.

Regarding the definition of green expenses, we expect some European MPs to require the use of the EU Taxonomy in the eligibility criteria of the Recovery Fund, at least for the the area of ecological transition. However, the delegated acts on the EU Taxonomy are due by the end of this year and the final report from the TEG can hardly be used as it stands because of its recommendation nature. Still, we believe that the use of the Taxonomy in the eligibility criteria of the Recovery Fund is a priority that must be considered in the design phase and not an afterthought exercise once the Fund is operating and the delegated acts adopted. In that case, it would come on the top of the EIB’s interventions that is reportedly willing to use the Taxonomy, bringing a significant amount of financial firepower “managed” using the Taxonomy.

8. WHAT’S NEXT?

The nature, scope and scale of ambition of the current proposal marks a “Europe's moment”. The branding of this program has been appropriately chosen as it will indeed lay the foundations for the “Next Generation”.

Such a blueprint is groundbreaking also because of this timing. It intervened just after the Karlsruhe Court’s ruling on the ECB’s pandemic purchase program[22]. The French-German tandem took note that we can no longer rely exclusively on monetary policies to prevent Eurozone’s implosion. Germany at last acknowledges that budgetary transfers and fiscal policies are of the utmost importance. It marks the comeback of politics and it is very welcome as we cannot expect Central Banks & Supervisors to solve on their own neither the sanitarian/economic crisis nor the climate crisis. Up until now, the ECB has had a very extensive interpretation of its mandate to prevent spreads broadening to overcome political gridlocks. It does so because of existing treaties’ limits. European Commission President insists that the European Parliament must provide the democratic accountability for the Recovery Plan “and have its say on the entire recovery package – just as it does on the EU budget”. To see other taboos falling will require a revision of European Treaties, for instance unanimity necessity for some matters (on tax topics), an ambition that French President Emmanuel Macron has been defending since the beginning of his tenure.

A number of critical ESG issues are hard to address at a national level or even at risk of being detrimental. Europe is the right scale for reshoring industries, economy-wide decarbonization, and food systems reforms (Made in Europe, in Western Europe, makes more sense than Made in France). The European Union is more than ever a sui generis political entity. It is transforming its very nature by turning green and social. Such a move would challenge the prognostics or critics about its alleged by design incapacity to advance social and environmental progress.

To go further:

[1] See our April Editorial: “Covid-19: a new (sustainability) model in the making?

[2] According to a “capital key” which is roughly based on countries’ GDP

[3] Own resources are under a ceiling, while national contributions account for the bulk of EU Funding, with limited autonomy.

[4] In this context, “Eurobonds” refer to common issuance of debt of Eurozone countries. However, the original meaning of the term is debt instrument that is denominated in currency other than the home currency of the country or market in which it is issued. The term often causes confusion when used out of context: for instance, the “Frugal Four” is more likely to oppose the former rather than the latter concept.

[5] A group of countries is reluctant the so-called frugal states (northerners), e.g. Sweden, Denmark, Austria, Netherlands, Poland, but they should rally Germany.

[6] The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) is often considered as a bedrock of European integration

[7] The proposal is to increase the Own Resources ceiling on an exceptional and temporary basis by 0.6% points. This increase will come on top of the permanent Own Resources ceiling - 1.4% of Gross National Income. The increase in the Own Resource ceiling will expire when all funds have been repaid and all liabilities have ceased to exist

[8] The own resources expression is misleading and confusing, it must be understood as contribution from Member States

[9] As a concession the recovery and resilience facility is embedded into the European Semester, meaning countries will not be free up from structural reforms

[10] According to a bargaining system of cashback for countries who are net contributors to the EU, which dates from Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s.

[11] First Commission estimates show that tourism, the social economy and the creative and cultural ecosystems could see a more than 70% drop in turnover in the second quarter of 2020.

[12] Bloomberg (June 2020), “Germany Just Unveiled the World’s Greenest Stimulus Plan”, Available here.

[13] The European industrial strategy aims at using the green and digital transformations to empower industry and SMEs. See there: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/european-industrial-strategy_en

[14] Such move would require rethinking of EU approach to State Aid/competition policies, which has been temporarily modified to enable state interventions meant to prevent collapse of companies.

[15] IDDRI, in a 2020 study, commissioned by the European Parliament, took stock of how the EU and EU Member States have responded to the challenges posed by the SDGs. The study analyses and compares the governance frameworks, institutions and mechanisms put in place in EU Member States and at the EU level to implement the SDGs. It in particular captures the roles and activities of national parliaments and presents a policy-relevant assessment of the ‘readiness’ to achieve SDGs by 2030.

[16] “A Just Transition Fund - How the EU budget can best assist in the necessary transition from fossil fuels to sustainable energy”. Available here: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/fr/a-just-transition-fund-/product-details/20200603CAN55547

[17] See The Economist (May 2020), California has a state wide cap-and-trade program. Companies importing electricity into the state can either specify its source, and hence the emissions with which it is associated, or be treated as if the electricity was generated by a relatively efficient natural-gas power plant.

[18] The EPPO is an independent Union body competent to fight crimes against the Union budget.

[19] See the letter sent to decision-makers across the EU). It has been coordinated by the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC) in coordination with Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) and CDP.

[20] See Financial Times (June 7, 2020), “Europe’s capitals take aim at €750bn recovery plan”

[21] See Patrick Artus, June 3, 2020 “The risk of very high important in recovery”

[22] The German Federal Constitutional Court has questioned whether the ECB is really purchasing government bonds to lift inflation in the Euro zone. It accuses the ECB to monetize debt to keep long-term interest rates low in all euro-zone countries, something considered as a violation of European treaties.