Insightful benchmark of climate and fossil fuels practices of French financial institutions and corporates by the AMF and the ACPR

10-minutes read

Last December, the French financial watchdogs have released two reports delving into the climate change related commitments, disclosure, and actual actions of French corporates, banks, investors and insurers[1]. The AMF and the ACPR’s observations and recommendations could serve as a yardstick or compass for market participants. They could also underpin forthcoming supervisory doctrines, actions or even sanctions, and inspire new regulations. It illustrates the growing activism of regulators and supervisors on ESG-related topics (see our Article on Greenwashing probes and climate litigation).

The first report digs into the climate-related commitments of French financial institutions and aims at monitoring climate commitments, which have been proliferating in the past year (notably “net zero” claims). The modalities and scopes of such commitments are analyzed and inconsistencies and loopholes highlighted. The report also examines fossil-fuel related policies put in place by market players and, for the first time, publishes estimates of banks, insurers and asset managers’ exposures to the oil & gas sector. On the other hand, the AMF has also thoroughly reviewed the non-financial and financial information published by 19 French issuers (including Air France, Michelin, Air Liquide, Legrand, Engie, Danone, Legrand, Schneider) to publish an overview of their climate-related practices, commitments and accounting impacts.

Those two major reports provide a granular level of analysis and information that must be known by corporates and financial institutions to ensure compliance with both existing and upcoming (e.g., CSRD) regulatory principles. This article aims at walking financial actors (i) and corporates (ii) through the Supervisors’ key recommendations.

***

Overview of the French financial institutions’ climate commitments

|

Evolution of the practices between 2019 and 2020

As compared to the 78% of banks and 65% of insurers who had committed or expressed their wish to commit in the near future{ to the alignment of their portfolios with a 2°C climate trajectory in 2019 (see the 2020 joint report of the AMF and the ACPR), 66% of the banks and 53% of insurers made additional commitments in 2020, mainly on the GHG emission reduction or on the alignment with the Paris Agreement. |

Climate commitments from major French financial participants (see Annex 1) cover several categories including:

- Internal policies for reducing or offsetting direct greenhouse gas emissions

- green financing commitments, exclusion and divestment policies,

- shareholder engagement and client support,

- alignment policies for complying with the objectives of the Paris agreement and efforts to ensure transparency on climate-related issues in line with the taskforce on climate-related financial disclosures (TCFD) framework.

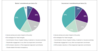

Graph 1: Distribution per item of the new commitments undertaken by French banks and insurers from January 1st, 2020

Source: ACPR Questionnaire 2021

Not only these commitments remain difficult to identify, compare and evaluate, as they have different scope and can be implemented in a more or less ambitious way, but 46% of the banks and 31% of insurers communicate on commitments without providing a target date.

To improve the traceability and reliability of commitments, financial institutions should ensure that documents contain easily accessible (e.g., in a single document) and comprehensive information on climate commitments, namely:

- date of entry into force

- timeline of the targets

- organizational scope

- investment scope

- quantified objective in terms of means

The growing weight of collective commitments through national or international initiatives should not make up for the lack of specificity in the articulation and consistency with individual commitments. Financial institutions still need to progress on the transparency of the objectives and the methodologies (e.g., measure and define the portfolios’ alignment trajectory, provide the green ratio funding, investment or exposure, measure impact and systematically provide the activities perimeters (scopes, asset types, operations types, coverage ratio…) as well as on the associated communication.

Fossil-fuel related policies (coal, oil and gas)

|

Evolution of the practices between 2019 and 2020

|

Even if the financial sector’s exposure to coal remains low – representing sensibly less than 1% of the assets - data issues still limit the methodologies and the measurement of coal exposure. With regards to oil & gas, the segmentation of the value chain and impacts remain challenging, so the estimates appear “very fragile”. Yet, the total exposure to oil & gas increased from 146 billion of euros in 2015 to 155 billion of euros in 2020, it has thus grown by more than 6% between 2015 and 2020. For coal as for oil & gas, the figures hide disparities between actors, in particular in terms of policies, adopted measures, perimeters, terminologies. Financial institutions need to step up their clarification and harmonization efforts as those are the cornerstones of the comparability of policies and risks.

Summary of the key recommendations formulated by the AMF/the ACPR

|

Fossil energies policies |

|

|

Exposure measurement and operational scope identification |

|

|

Exit of the coal strategy |

|

|

“Non-conventional” energies |

|

Focus on the accompaniment of customers and shareholder engagement

The accompaniment of customers policies and shareholder engagement are identified by the institution as transition levers for the financial sector. Yet, if engagement and dialogue policies fail, only 33% of banks and 35% of insurers (against 68% of asset managers) consider cession or divestment. While institutions also put forward the training provided to employees on climate-related issues, it should be more precise (and not simply tackling CSR issues) and be evaluated. With regards to asset managers specifically, even if climate shareholder activism is part of the practices, it is still not a major driver for engagement and voting actions.

Corporates’ carbon reporting still lacks transparency, comparability and consistency.

Despite improvements, the AMF found that corporates still need to progress on the comparability, the long-term monitoring and the transparency provided to market participants. Only few companies are already providing the information that is soon to be required by the new European regulatory framework (CSRD) or even the information on both physical and financial data already required by investors. To meet the growing expectations of stakeholders as well as the strengthened regulatory framework, companies – of all sizes – need to step up their efforts.

Publication of carbon data and other KPIs

The AMF recommends that corporates publish detailed information by emission scope, by main emission categories, by subsidiary and when relevant by region and business activity.

When items are excluded from the organizational and/or operational scope, the reason for exclusion should be systematically provided. For instance, if emission sources are excluded to calculate the scope 1 and scope 2 GHG emissions, the corporate should indicate the non-material nature of exclusions (e.g., how it does not relate to the business model). A sufficient and clear level of information should allow the reader to understand the main methodological choices made to calculate GHG emissions.

Carbon neutrality commitments

In light of the increasing number of carbon neutrality commitments by corporates in various sectors in France and abroad, this chapter echoes to the AMF’s initial conclusions and issues identified on companies and net neutrality.

Focus: companies and net neutrality

The AMF acknowledges that companies have multiple levers (e.g., energy sources, industrial processes, transport of materials or products, waste management and recycling, emissions linked to the use of products by customers…) for action to contribute to global carbon neutrality, which makes it necessary to specify the measures and establish priorities in order to define a strategy suited to the challenges involved.

The companies’ priority must be to contribute to carbon neutrality first and foremost by reducing GHG emissions (carbon footprint) according to a pathway in line with science and covering relevant part of its business (scopes 1, 2 & 3).

For companies, a demanding approach involves to:

The targets should be associated with a detailed transition plan (as specified by the EU on the CSRD).

As far as possible, companies can make additional efforts to contribute to the global carbon neutrality objectives by other measures such as:

When it comes to carbon offsetting (financing projects outside companies’ value chain), quality criteria, including a “do not significant harm” principle, additionality or impact, measurability and permanence of the sequestered/avoided emissions, regular verification by an independent third party and the uniqueness of the carbon credits generated, must be fulfilled.

|

Among the 19 issuers studied in the sample, 13 of them have made carbon neutrality commitments, amounting approximately to 70% of the sample. Yet only few companies offer precise definitions for the terms used (e.g., carbon neutral or carbon neutrality). Not only companies should clarify all terminologies, but they should also provide information on the emission sources and categories covered by the commitment and potential carbon offsetting.

Even if the comparison is difficult as there are lingering differences between ambition levels, baseline years and intermediate dates selected, objectives (breadth of scope, changes in scope, presentation of gross and net figures), and geographies (due to regulation, European operations may have more ambitious targets), the AMF found that companies which targets have been validated by SBTi set slightly more ambitious objectives (-4.4%) than others (-3.8%). The annual emissions reduction rates for Scopes 1 and 2 vary greatly from one company to another, ranging from -1.5% to -11.8%. The difference is narrower in Scope 3, between -1.3% and -5.5% (see the table below).

The scope applied, and whether it is current, constant or on the basis of the baseline year, is an important factor in determining whether targets have been achieved. Corporates should be able to back their carbon neutrality commitments with short and medium-term GHG emission reduction targets (for all scopes, both in absolute terms and in intensity), detailed action plan (e.g., at production site level), evidence of operational implementation as well as investment plans’ estimate.

Accounting impacts

Corporates should enhance the transparency on the impacts of climate change by providing information on:

- impairment tests, key assumptions involved in the valuation work, sensitivity tests and the sources of uncertainty

- the treatment of GHG emissions allowances in financial statements

When emission rights relating to pollutant emissions plans are significant for the company – including GHG emission rights and energy saving certificates – the AMF recommends specifying the amounts at play, the accounting treatment applied and the associated impact on the financial statements.

Amid rising greenwashing fears, it is important that corporates ensure greater information consistency between financial statements and other communication. Overall, the AMF recommends monitoring regulatory changes and assessing the expected or potential impacts of transition plans on business models, recognizing and mentioning these impacts in financial statements, where relevant.

In the case of financ

ing through the issuance of or investment in “green” financial products, disclosing the characteristics of these products and the associated accounting treatment, when considered material could also be relevant.

Summary of the key recommendations formulated by the AMF

|

GHG emission data scope |

|

|

Targets |

|

|

Physical risks |

|

|

Carbon neutrality |

|

|

Offsetting |

|

|

Communication and continuous monitoring of commitments |

|

|

Consequences for the financial statements |

|

[1] Second ACPR/AMF Report on the monitoring and evaluation of the climate-related commitments of financial institutions in Paris, December 2021 ; AMF Financial and non-financial overview of corporate carbon reporting, December 2021

[2] The sample of companies studied by the AMF and the ACPR was similar in the 2020 and 2021 Reports.

Appendices

Annex 1: sample of the French financial institution groups used by the AMF and the ACPR in the Report on the monitoring and evaluation of the climate-related commitments of financial institutions in Paris

The sample is composed of 9 Banks, 17 Insurers and 20 Asset Managers (see the table below).

|

Banks |

1. AGENCE FRANCAISE DE DEVELOPPEMENT (AFD) 2. GROUPE BNP PARIBAS 3. GROUPE BPCE 4. GROUPE CRÉDIT AGRICOLE SA 5. GROUPE CAISSE DES DEPÔTS 6. GROUPE CRÉDIT MUTUEL 7. HSBC France 8. LA BANQUE POSTALE 9. GROUPE SOCIÉTÉ GÉNÉRALE |

|

Insurance groups |

1. ALLIANZ HOLDING France 2. AVIVA France 3. AXA SA 4. BNP PARIBAS CARDIF 5. CCR 6. CNP ASSURANCES 7. COVÉA 8. CRÉDIT AGRICOLE ASSURANCES 9. GENERALI France 10. GROUPAMA SA 11. GROUPE DES ASSURANCES DU CRÉDIT MUTUEL 12. MACSF SGAM 13. MUTUELLE ASSURANCE DES COMMERÇANTS ET INDUSTRIELS DE FRANCE ET DES CADRES ET SALARIÉS DE L’INDUTRIE ET DU COMMERCE 14. NATIXIS ASSURANCES 15. SCOR SE 16. SGAM AG2R LA MONDIALE 17. SOGECAP |

|

Asset managers |

1. AMUNDI ASSET MANAGEMENT 2. AVIVA INVESTORS France 3. AXA INVESTMENT MANAGERS PARIS 4. AXA REIM SGP 5. BNP PARIBAS ASSET MANAGEMENT 6. CM-CIC ASSET MANAGEMENT 7. COVÉA FINANCE 8. CPR ASSET MANAGEMENT 9. EUROTITRISATION 10. FEDERAL FINANCE GESTION 11. GROUPAMA ASSET MANAGEMENT 12. HSBC GLOBAL AM France 13. LA BANQUE POSTALE ASSET MANAGEMENT 14. LYXOR ASSET MANAGEMENT 15. LYXOR INTERNATIONAL ASSET MANAGEMENT 16. NATIXIS INVESTMENT MANAGERS INTERNATIONAL 17. OFI ASSET MANAGEMENT 18. OSTRUM ASSET MANAGEMENT 19. SOCIÉTÉ GÉNÉRALE GESTION 20. SWISS LIFE ASSET MANAGEMENT FRANCE |

Annex 2: sample of the French listed companies reviewed by the AMF for the Report “Financial and non-financial overview of carbon reporting”

The overall analysis is based exclusively on a review of the information published by a sample of French listed companies, belonging to 10 high emissive sectors.

|

Sectors |

Companies |

Chapter 1 |

Chapter 2 |

Chapter 3 |

|

Airlines |

Air France KLM SA *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

Auto components |

Michelin SCA *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

Compagnie Plastic Omnium SE *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Faurecia SE *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Valeo SA* |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Automotive |

Renault SA *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

Trigano SA |

X |

|

X |

|

|

Building products |

Compagnie de Saint Gobain SA *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

Chemicals |

Air Liquide *# |

|

|

X |

|

Construction and engineering |

Bouygues SA # |

X |

|

X |

|

Eiffage SA # |

X |

|

X |

|

|

Vinci SA *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Construction materials |

Imerys SA |

X |

|

X |

|

Holcim # |

|

|

X |

|

|

Electrical equipment |

Legrand SA *# |

|

|

X |

|

Schneider Electric SE *# |

|

|

X |

|

|

Electric utilities |

Electricité de France SA *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

Food products |

Danone SA *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

Multi-utilities |

Engie SA *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

Suez SA # |

X |

|

X |

|

|

Veolia Environnement SA *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Oil, Gas and Consumable Fuels |

Gaztransport et Technigaz SA* (GTT) |

X |

|

X |

|

Total SE *# |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Total |

|

19 |

13 |

23 |