- COP 25’s failure to have the World’s major economies revise upwards their CO2 emissions reduction targets filled in Paris in 2015 at the COP21 (see Morning line issue of 05/12/2019: Deciphering the daunting challenges of COP25 for a discussion of the summit’s main underlying challenges) should not overshadow EU’s mounting planned effort in the field of climate action, in particular on the financing side. In this field, recent weeks saw progress/announcements of initiatives at EU level aimed at easing the financing of ‘’green’’ assets (EU Taxonomy) and drying up the financing of most fossil fuel assets (EIB). We analyse these recent policy developments as well as their potential implications, if any, for the financing of fossil fuel assets (oil, gas and coal).

- After weeks of intense negotiations, the European Triade (EU Parliament, EU Commission and EU Council) at last reached an agreement on the EU Taxonomy project last 19 December (see Morning line issue of 19/12/2019). Such agreement marks a key progress in the implementation of EU’s Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth aiming to reorient capital flows towards sustainable investment published in March 2018 by the European Commission.

- A corner stone of the Action Plan, the Taxonomy is meant to provide a unified classification system determining under which circumstances (criteria and thresholds) an economic activity can be considered as “sustainable”, hereby preventing fragmentation of classification systems in EU Member States as well as “greenwashing” – a situation of unfair competition when a financial product is marketed as environmentally friendly without being so. For this purpose, the Taxonomy provides technical screening criteria for economic activities for six sustainability objectives. For now, technical screening criteria have been developed for two objectives: climate change mitigation or adaptation. In the field of climate change mitigation, noteworthy is all criteria being set with the underlying objective of bringing the EU to a strict climate neutrality position by 2050 (i.e. zero net CO2 emissions by then – see below). The scope of the Taxonomy will be enlarged to provide similar criteria for four additional objectives: water and marine resources, circular economy, pollution prevention & control and biodiversity & ecosystems.

- Combined with other disclosure-related measures contained in the Action Plan, the Taxonomy will result in a requirement in which firms will have to disclose the degree of environmental sustainability of their mainstream funds and pension products marketed as environmentally friendly or to provide disclaimers why it is not the case (comply or explain). Moreover, firms subject to the Non-Financial Reporting Directive will have to provide information related to the Taxonomy (e.g. share of revenues or CAPEX taxonomy-compliant). Furthermore, for every EU Member State, public measures, standards or labels related to financial products or corporate bonds labelled as environmentally sustainable will also have to abide by the criteria of the Taxonomy. The requirements related to the climate objectives of the Taxonomy are due to apply from December 2021. The requirements for the other four objectives are due to apply from 31 December 2022. One important use of the EU Taxonomy is to serve as a reference for the emerging EU Green Bond Standard (GBS)[1].

- As we already highlighted last July when discussing the draft proposal submitted by the Technical Expert Group (TEG- see # 13 infra. / ENR Monthly - Taking a deep dive in IEA’s 2019 World Energy Outlook), from the perspective of energy assets, the EU Taxonomy project reveals key energy policy options. The CO2 emissions thresholds set by the TEG (100g CO2e per KWhe now, declining to 0 by 2050) mean the exclusion from the list of sustainable activities of all fossil fuel-related assets. Such exclusion therefore concerns natural gas, in particular when used for power generation purposes, given the present state of the technology. Gas-fired plants generally emit around 400g CO2e per KWhe, whilst the prospect of mitigating such impact through carbon capture remains remote at this stage, CCS[2] processes being still at an infant stage. From the perspective of nuclear energy, the key caveat of the Taxonomy lies in the ‘do no significant harm” (DNSH) requirement. This requirement stipulates that in addition to a “substantial contribution” (defined by the technical screening criteria) to one of the six sustainability objectives, an economic activity qualified as environmentally sustainable under the Taxonomy cannot cause harm to any of the remaining five objectives. This means not undermining any of the six sustainability objectives of the Taxonomy. For illustration, while nuclear is a carbon-free source of energy contributing towards climate change mitigation objective, there are concerns about the potential “significant harm” caused by nuclear waste to biodiversity and ecosystems.

- The abovementioned agreement reached by Council and Commission at the end of last year, confirmed the de facto ban of natural gas, while leaving the case of nuclear subject to the DNSH review on environmental externalities. The latter should be undertaken by experts gathered in the same fashion as the TEG. In practice, it is very likely to result in the exclusion of nuclear power from the EU Taxonomy.

- Just a few days ahead of the agreement on the EU Taxonomy was reached, on 13 November, the European Investment bank (EIB), EU’s financing arm, unveiled its new lending policy and pledged to phase out fossil fuel financing, removing €2bn of yearly investment from its lending portfolio. The Bank, which has reportedly lent €13.4bn to finance fossil fuel infrastructure since 2013 (of which more than €9bn went to natural gas pipelines & distribution networks), “will no longer consider new financing for unabated, fossil fuel energy projects, including natural gas, from the end of 2021 onwards”.

- In the field of power generation, the newly adopted 250 gCO2e per kWhe criterion (against the former 550g CO2e per kWhe) applies to all technologies. This shall de facto lead to the exclusion of natural gas whose combustion emits CO2 in excess of the abovementioned threshold (see above). As an exception to this general rule, the EIB will nonetheless support natural gas-fired power plants but on the condition the latter provide a credible plan to blend increasing shares of low-carbon gas (mainly hydrogen) over the economic lifetime of the project, such that the emission standard above is met on average.[3] The Bank will also seek to support research and development into the use of hydrogen by gas turbine technology.

- Such announcements along with the discussions on the EU Taxonomy project come as no surprise given i/ the institutional framework governing EIB’s action (the Bank’s Board of Governors comprises Ministers designated by each of the 28 Member States, usually Finance Ministers) and ii/ the abovementioned considered role of the EU Taxonomy as the corner stone of EU’s climate action.

- Such regulatory developments follow numerous, highly-publicized statements by some financial institutions of their intention to step down or even stop the financing of fossil fuels. Let us mention here the case of AXA, after the French insurer stated in early 2018 its intention to divest from companies most exposed to coal-related activities[4]. In parallel, all major international banks are under increasing pressure from various stakeholders (NGOs but also a growing number of shareholders) to better align their lending policy with mounting climate challenges and revise their lending policy accordingly.

- As seen with AXA’s update investment policy, coal extraction has become a central issue for investors having adopted an ESG/SRI approach. However, a distinction needs to be drawn between the need for thermal coal, supplied to fuel power plants and blast furnaces, and metallurgical coal (i.e. coke) that is employed primarily in the production of steel. In our coverage universe, three issuers are particularly present in the coal segment: (1) Anglo American generates 20% of its revenue in this segment, but with only 8% from thermal coal; (2) BHP generates 21% in this segment, but only 4% from thermal coal; and (3) Glencore generates 6% in this segment (13% excluding trading activities), but only 4% from thermal coal (9% excluding trading activities). Note that, in the case of Glencore, thermal coal represents the second largest source of activity (in volume) for its trading activities (Glencore not disclosing what revenue is contributed by this segment). Finally, in recent years, leaders in the Metals & Mining sector have largely taken onboard ESG criteria (water management, deforestation, impact of carbon emissions, etc.) and, in their communication, have made much of their reduced involvement in coal extraction. On the occasion of its Investor Day last December, Anglo American indicated it intended to exit thermal coal (but without setting a timeframe). As for Glencore, under pressure from activist investors, it indicated it will not grow its thermal coal output beyond current levels.

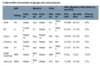

- All these elements have sparked numerous questions among investors over a possible deterioration of fossil fuel companies’ funding capabilities. When addressing such issue, one has to keep in mind that the abovementioned developments, either at public or private level, mainly concern capital markets financing, while the bulk of commodities projects remains financed through bank lending, in particular via asset-centric non-recourse financing instruments[5]. Another way to examine the question is to look at the credit fundamentals of the major players in the oil & gas and coal sectors (see table below), namely BP, Chevron, Exxon, Shell and Total (oil & gas), Anglo American, BHP and Glencore (coal).

- The results displayed in the table below are self-explanatory, with all these players…

- i/ … Enjoying solid investment-grade ratings (even A-category ratings in the case of oil & gas majors). Noteworthy is rating levels explicitly incorporating a measurement of issuers’ liquidity position and access to broad sources of funding;

- ii/ … Displaying hefty and diversified cash flow generation, relative to net debt positions (as measured by the share of internal cash generation, i.e through the funds from operation aggregate, relative to net debt). In the cases of Anglo American and BHP, as highlihted above, the share of coal in consolidated revenue stands at around 20% and more importantly at 8% and 4%, respectively for thermal coal extraction, with activities in such commodities as copper and iron ore totaling 40% and 65%, respectively. The share of copper and iron ore in these companies’ revenues is worth highlighting given the importance of these commodities for the manufacturing of equipments[6] / metals[7] both highly-needed for the purpose of energy transition. The latter activities can be considered as enabling activities in the EU Taxonomy’s approach (“greening by”), for they are needed for the decarbonisation of other activities (for instance, use of steel for the manufacturing of renewable energy equipment).

- The conclusions we can draw from these simple observations are twofold:

- i/ Even though there are growing signs of tightening access to a “universal” investor base given the rise of ESG-oriented funds or the tightening of investment policies from a set of large investors with a “global” mandate, these companies continue to enjoy wide access to capital markets;

- ii/ Their high levels of internal cash generation and degree of operational diversification mean, holding all else equal, they could for a great part self-finance a substantial share of the potential investments in the most controversial assets (namely production of oil sands as well as deep offshore exploration in the oil & gas industry and extraction of coal in the mining industry, in particular thermal coal).

- All in all, for the time being, these elements suggest a prevailing inconsistency between public discourse and market reality in terms of climate change. In particular, the EU Taxonomy provides a roadmap of a low-carbon economy by mapping which economic activities are compatible with it. The technical screening criteria of the taxonomy clearly show that there is no place for coal and oil while the future of gas remains highly uncertain, which means a thorough decarbonization of the economy would considerably modify value of such fossil fuel assets.

- Nevertheless, a look at credit ratings of leading oil & gas and coal mining companies reveals a surprisingly strong position in financial terms and continued access to broad sources of funding. This means that such repricing is not yet happening. In our view, in light of the trends likely to affect the energy sector in the coming decades, the question is not whether but rather when and at which pace it will happen. Longer it is delayed, more abrupt and disorderly this repricing will be. Meanwhile, should it occur, it would be extremely differentiated across companies depending on the carbon intensity of their production (CO2 emissions from oil production per megajoule are for instance almost four-fold higher in Venezuela or in Canada than in Saudi Arabia, with high heterogeneity as well in breakeven prices). This situation is known as ‘transition risk”, a key channel through which climate change can pose future risk for financial stability if climate policies and market reaction result in a swift and large-scale repricing of assets.

- In the oil & gas sector, three companies – namely Repsol, Total and Shell – clearly differentiate themselves by having designed scope 1 to 3 emissions indicators (i.e. that include the emissions of sold products, expressed in tCO2/GJ or tCO2/kBTU)) and use it to steer their transition with 2030, 2040 or 2050 targets. In December 2019, Repsol has announced that the company will direct its strategy towards achieving net zero emissions by 2050 (see Section 2 dedicated to energy companies).

[1] Under the draft EU GBS proposal, only those bonds aimed at financing green assets as defined by the EU taxonomy can claim compliance with the EU GBS and may be marketed as such.

[2] Carbon capture and storage.

[3] Such exception is itself consistent with the inclusion in the EU Taxonomy of activities related to the production, transmission and use of low-carbon gases such as biomethane and hydrogen.

[4] AXA IM’s policies exclude inter alia companies that derive 30% or more of their revenue, mining companies that extract more than 20 milliontonnes of coal per year, Power generation companies that have 30% or more of electricity generation capacities powered by coal from thermal coal, Power generation companies that plan to expand coal power generation capacity by more than 3000 MW in the medium run but also exclusion criteria for tar sands.

For full details, see AXA IM Climate Risks Policy (May 2019):

[5] Also known as project finance schemes.

[6] Extensive use of copper in power infrastructure to convey electricity.

[7] The primary of iron ore being the production of steel.