Fit for 55: bringing EU’s decarbonisation efforts to the next level

21-minute read

On 14 July, the European Commission adopted a set of 13 proposals, the so-called “Fit for 55 package”, to make the EU's climate, energy, transport and taxation policies commensurate for reducing net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels. Such announcement was eagerly awaited after the agreement reached last December at the European Council on more ambitious GHG emission reduction targets.

The EC’s Fit for 55 encompasses a wide range of regulations/directives, sectoral targets and other policy instruments to accelerate decarbonisation of such sectors as buildings, industry and mobility, but also to accompany the social implications of the various targeted technology disruptions and behavioral changes.

In broad terms, it relies on four distinct pillars:

i/ Strengthened carbon pricing within the EU, through proposed toughening and extension of the ETS to new sectors (road and maritime transportation, buildings). In this perspective, the proposed introduction of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) for a selected number of sectors covered by the ETS (cement, iron / steel, aluminum, fertilizers and electricity generation) aims to create a level playing field with EU’s trade partners. The CBAM is to be rolled out in synch with free allowances phasing-out to prevent distortion of competition.

ii/ Increased EU-wide targets in sectors / fields set to be the pillars of EU economy’s decarbonisation: renewable energies, low-carbon fuels such as low-carbon hydrogen and biogas, energy efficiency, and use of land and forest for carbon capture and sequestration;

iii/ New rules and incentives for the production and use of low-carbon fuels in the buildings and mobility sectors;

iv/ Mobilization of funds drawn from the toughening of the ETS to foster innovation and mitigate social impact of the targeted disruptions in EU's energy supply.

Table 1. Overview of the EC’s Fit for 55 package

Source: European Commission

The abovementioned proposed strengthening/enlargement of the ETS is likely to be the main policy instrument underpinning the targeted disruptions in buildings, industry and transport. While most of the needed policy instruments are there to support decarbonisation in buildings and transport, we see some key pending issues in the industry sector which should be clarified in the coming months / years:

i/ Review of emissions benchmarks used for allocation of free allowances to the various activities benefitting from the carbon leakage mechanism and

ii/ Potential inclusion of indirect emissions in the scope of CO2 emissions to determine the embedded carbon content of those imported industrial goods subject to the proposed CBAM.

All in all, while the climate ambition underlying the Fit for 55 package is there, acceptability of certain measures across the society (ban on the sale of new internal combustion engines in light-duty mobility by 2035, expected increase in fuel costs in particular for aviation, etc.) may prove challenging to achieve. The review of EC's proposals by the EU Council and EU Parliament is likely to spur intense debate, with the underlying risk of a weakening of the package’s underlying climate ambition. In any case, it will not enter into force before early 2023.

***

In depth Analysis

On 14 July, the European Commission (EC) adopted a set of proposals, the so-called “Fit for 55 package”, to make the EU's climate, energy, transport and taxation policies fit for reducing net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels.

Such announcement was eagerly awaited after the agreement reached last December at the European Council on more ambitious GHG emissions reductions. After months of intense negotiations among Member Union (EU) by 2030. By then, the objective is to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions not by 40% (compared with their 1990 level) but by 55%. The setting of these more ambitious decarbonisation objectives for the European Union was first officially mooted in December 2019 by the newly installed European Commission when it presented its Green Deal. At the time, it met with opposition from several Member States, which spurred intense negotiations at European Council level before an agreement was eventually reached.

The announcement of this package of measures is part of an international context of increased climate change awareness, as evidenced by the US rejoining the Paris Agreement in the wake of Joe Biden's election and by China now striving to achieve climate neutrality by 2060 (see our articles “The global race to net-zero: what about hic et nunc decisions?” and “President Biden’s executive order "tackling the climate crisis" fleshes out his campaign promises on climate change”). For the EU, which has made the achievement of carbon neutrality by 2050 a priority objective as part of its Green Deal and has been able to cut its GHG emissions by 24% over the past thirty years (Period 1990-2019: see here), the announcement of the EC's Fit for 55 package is timely. It indeed comes at a time of general consensus around the fact that achieving the new intermediary GHG emissions reduction targets will involve more efforts, but also greater technological leaps than those observed over the period 1990-2020, in particular in such hard-to-abate sectors as buildings, industry and mobility.

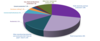

Figure 1. Breakdown of EU’s 2017 CO2 emissions by sector (%)

Source: European Environment Agency

*Sectors followed by an asterisk are covered by the current ETS

Despite their modernisation over the past three decades, these sectors (buildings, industry and mobility) continue to heavily rely on fossil fuels used as a feedstock (case of chemicals and steel manufacturing) and/or as an energy vector (case of the buildings and mobility sector). Together these sectors still make up for nearly 50% of EU’s CO2 emissions (of which around 25% for road transport, now nearly at par with the power generation sector – see chart above). At the same time, despite increased Member States’ focus on energy efficiency in the recent past, the buildings sector alone represents more than 15% of EU's overall CO2 emissions.

These data show that the EU's decarbonisation policy instruments (EU’s carbon allowance market, the so-called EU Emissions Trading Scheme – ETS – as well as sectoral regulation and subsidies schemes) must now heavily focus on emissions in these sectors, while continuing to incentivise a switch to clean generation technologies in the power sector. This is precisely what the EC's Fit for 55 Package aims for. Not only is it based on an unprecedented toughening and enlargement of the EU ETS, but it also provides for the introduction of new regulations in mobility and buildings as well as new support schemes for the development of clean fuels in these sectors.

EC's set of proposals now needs to be submitted to the EU Council as well as to the EU Parliament for approval. EU legislative process is lengthy as both bodies are entitled to make amendments to EC's proposals and have their say on the finalised draft Directive. If the Council and the Parliament cannot agree upon amendments, a second reading takes place. In the second reading, the Parliament and Council can again propose amendments. Parliament has the power to block the proposed legislation if it cannot agree with the Council. If the two institutions agree on amendments, the proposed legislation can be adopted. If they cannot agree, a conciliation committee tries to find a solution. Both the Council and the Parliament can block the legislative proposal at this final reading (see a simplified EU standard decision-making procedure here).

The timetables included in EC’s various proposed regulations reflect EC’s anticipation that the package will not enter into force before early 2023.

In EC’s own words, the package strives to strike the “overall balance between fairness, emissions reductions, and competitiveness and illustrates how the different policies work together”.

It is therefore a threefold ecological, economic and social transformation that EC's set of proposals aims to underpin by 2030 so as to ensure the achievement of EU’s new intermediate decarbonizaton target.

EC’s Fit for 55 relies on four distinct pillars:

i/ Strengthened carbon pricing within the EU, through proposed toughening and extension of the ETS to new sectors (road and maritime transportation, buildings). In this perspective, the proposed introduction of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) for a selected number of sectors subject to the ETS aims to create a level playing field with EU’s trade partners;

ii/ Increased EU-wide targets in sectors / fields set to be the pillars of EU economy’s decarbonisation: renewable energies, low-carbon fuels such as low-carbon hydrogen and biogas, energy efficiency and use of land and forest for carbon capture and sequestration;

iii/ New rules and incentives for the production and use of low-carbon fuels in the buildings and mobility sectors;

iv/ Mobilization of funds drawn from the toughening of the ETS to foster innovation and mitigate social impact of the targeted disruptions in EU's energy supply.

Finally, implementation of EC’s proposed Fit for 55 package relies on a complex articulation of objectives and measures between the EU and the 27 Member States as part of the Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) introduced in 2018. The rules governing the strengthened / enlarged ETS are set at EU level to achieve the EU-wide target of 55% GHG emissions reductions by 2030 from 1990 levels, while the revised ESR empowers Member States to take national action to tackle emissions in the buildings, transport, agriculture, waste and small industry sectors. The principles for attributing the relative effort to each Member State remain the same as before. Their different capacities to take action will continue to be recognised by setting national targets based on GDP per capita, with adjustments to take national circumstances and cost efficiency into account.

***

The overhaul of the EU ETS proposed by the EC broadly follows the lines mentioned in the public consultation undertaken last autumn. EC’s proposals aim to align ETS’ functioning rules with the new intermediate GHG emissions reduction targets set for 2030, this through two main levers: the inclusion of new sectors (buildings, road and maritime transport), and the strengthening to the rules applicable to the various sectors already covered by the ETS (power, refining, chemicals, cement, iron/steel, aluminum, domestic aviation), this via the accelerated reduction of available allowances in the market as well as through the implementation of various restrictions surrounding the free allocation of allowances to sectors subject to the so-called “carbon leakage” rule (see below).

Inclusion of new sectors: maritime and road transport, buildings

As expected, following last months’ leaks, EC’s proposals provide for the extension of the ETS to three new sectors: maritime transport, buildings and road transport.

As part of the considered set-up, emissions from the maritime sector will be simply added to the list of those already covered by the ETS, while those from the buildings and road transport sectors will be covered by a new, separate cap-and-trade system which itself will be tied to the "main" ETS.

This new trading scheme will be designed with a view to regulating fuel suppliers rather households and car drivers, with a cap on emissions operational from 2026 onwards. While it makes it clears in its package that the system primarily aims to incentivize fuels suppliers to decarbonize their product to reduce the cost of compliance with ETS, the EC recognises that it is likely to drive fuels prices up and ultimately raise social issues. Interestingly, one may account for the proposed introduction of a separate ETS for buildings and road transport by EC's intention to transparently allocate the additional income from the allowances auctions to the financing of the newly-created Social Climate Fund (SCF), this to specifically tackle the risk of increased energy or mobility poverty coming from the extension of the trading scheme to these two sectors' emissions (see below).

Accelerated reduction of allowances auctioned and in circulation

In its package, the EC proposes that emissions from the current EU ETS sectors be reduced by 61% by 2030, compared to 2005 levels. This represents an increase of 18 percentage points compared to the

current -43% contribution from the system to the EU's climate target, with three underlying proposed pillars:

i/ A steeper annual emissions reduction factor of 4.2% (instead of 2.2% per year under the current system);

ii/ A one-off reduction of the overall emissions cap by 117 million allowances (‘re-basing');

iii/ A gradual removal of emissions allowances for the aviation sector, which is already covered by the EU ETS, this with a view to moving to full auctioning of allowances by 2027 to create a stronger price signal to drive emissions reduction in this sector (see below).

Indirect toughening of the carbon leakage mechanism

Among the measures expected from the European Commission was also an overhaul of the so-called carbon leakage mechanism. Let’s recall that such mechanism allows certain sectors at risk of relocating outside the EU in the event of increased carbon constraint to continue to receive free allowances within the framework of the ETS up to a certain point in time. The free allocation of these allowances in the steel, aluminum, chemicals and refining sectors itself results from a relatively complex, benchmark-based procedure.

As part of an ongoing review of this mechanism, the EC is proposing three levers for reducing free quota allocations:

i/ As mentioned above, an overall steeper annual emissions reduction factor of 4.2%, this to reduce the overall amount of allowances available either through auctioning or through allocation free of charge;

ii/ The broadening of the scope of installations receiving free allowances to those using zero-carbon / low-carbon technologies;

iii/ The conditionality of the allocation of free allowances, based on the decarbonisation efforts undertaken by the concerned installations.

The EC also mulls toughening benchmark emissions from 2026 onwards with a view to shifting more free allocations to the sectors proving the hardest to abate.

Gradual introduction of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)

In order to create a level playing field for most of the activities subject to this ongoing overhaul of the carbon leakage rules and therefore prevent the risk of such activities relocating outside the EU in countries with lower emissions reduction ambition, the EC proposes, as was expected, the introduction of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) covering five activities: cement, iron/steel, aluminum, fertilizers and electricity generation. Since the announcement, in December 2019, of the so-called “Green deal” to accelerate EU economy’s decarbonisation (see above), the EC has been working on a scheme allowing the integration of the carbon component of a certain number of imported industrial products with substantial embedded carbon emissions, this within a framework compatible with WTO rules.

The system will be fully operational from 2026 onward, following a transition period from 2023 to 2025. During this transition period, EU importers of the concerned goods will only have to declare annually the quantity of goods and the amount of associated embedded emissions. From 2026 onwards, in addition to this reporting obligation, EU importers will have purchase CBAM certificates expressed in €/ton of CO2 to cover the amount of their imports' embedded emissions. These CBAM certificates will mirror the EU ETS so as to ensure the same “carbon price” will be paid for domestic and imported products. In the sectors covered, CBAM will therefore be gradually phased-in while free allowances under the carbon leakage mechanism are phased out.

That said, regarding the scope of carbon emissions covered, some elements announced on 14 July depart from the elements that leaked last month. The CBAM will only apply to “direct” (scope 1) CO2 emissions emitted during the production process of the products covered. By the end of the transition period, the EC will evaluate how the CBAM is working and whether to extend its scope to more products and services - including down the value chain, and whether to cover so-called ‘indirect' (scope 2) emissions (i.e. carbon emissions from the electricity used to produce the good). For some sectors such as alumium production whose carbon footprint predominantly (80%/90%) takes the form of indirect emissions, the introduction of the CBAM is likely to have limited impact at least until 2026.

Various sectoral measures to accelerate decarbonisation in hard-to-abate activities

In parallel, the Fit for 55 includes a series of regulations, targets and policy frameworks to spur decarbonisation of the buildings and mobility sectors.

Alongside the proposed strengthening/extension of the ETS in the transport sector (see above), the Fit for 55 package includes three main proposals promoting cleaner vehicles, namely:

i/ Revision of the CO2 emission standards for new cars and vans. The EC proposes that emissions from cars be reduced by 55% by 2030 and that new cars have zero emissions by 2035. For vans, it proposes an emission reduction target 50% by 2030 and zero emissions by 2035.

In its proposed amended regulation, the EC views such strengthened emissions standards as a key incentive for carmakers to deploy increasing share of zero-emission vehicles on the EU market. Interestingly, the EC takes a restrictive approach to this market segment, considering that “the scope of zero-emission vehicles currently include battery electric vehicles (BEVs), fuel-cell and other hydrogen powered vehicles (FCEVs). Under such approach, “low-emission vehicles, which also include well performing plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV)”[1], have some role to play but only in a transitional perspective.

Under this zero direct emissions-based approach, natural gas-fueled vehicles would not comply with the proposed strengthened emissions standards by 2035 and would find themselves excluded from the new vehicles market in the two vehicles categories concerned, even those fueled by biomethane with proven indirect climate benefit[2].

[1] Zero- and low-emission vehicle’ (ZLEV) means a passenger car or light commercial vehicle with tailpipe emissions from zero up to 50 g CO2/km, i.e. battery electric vehicles (BEV), fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEV) and certain plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV).

[2] Being a near pure form of methane, biomethane brings indirect climate benefits. While its combustion emits CO2 in the same proportions as that of natural gas, its production allows the removal of GHGs, mainly CO2 and methane, that would have been otherwise released in the atmosphere upon decomposition of the organic raw material used as feedstock for biogas production. Methane being a very potent GHG, biomethane’s carbon balance is therefore nearly neutral from a CO2e perspective using life cycle analysis, even after factoring in (i) the CO2 release upon final combustion as well as (ii) the anaerobic digestion-related GHG emissions, mainly in the form of direct (scope 1) GHG releases during the process and the carbon content (scope 2) of the energy consumed.

Table 2. Proposed revision of CO2 emission standards for cars and vans: projected % of ICEVs/PHEVs/BEVs/FCEVs in new sales

Source: European Commission

ii/ Introduction of the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation which ensures the necessary deployment of interoperable and user-friendly infrastructure for zero-emission vehicles (charging points and refueling stations), namely BEVs and FCEVs. This proposed regulation includes mandatory targets for alternative fuels infrastructure to support penetration of cleaner vehicles.

To this end, the EC proposes fleet-based targets to ensure that for each BEV registered in a Member State, 1 KW in charging capacity is installed. Following the same rationale, to ensure full connectivity across the TEN-T network of EU highways, EC’s proposal introduces the obligation to deploy 300 kW capacity provided by fast-charging point (with at least one of a capacity of 150 kW)per 60 km stretch of the TEN-T core network by 2025 and 600 kW capacity by 2030.

For hydrogen refueling, under EC’s proposed scheme, one station will have to be available every 150 km along the TEN-T core network and in every urban node serving both light duty vehicles including passenger cars and heavy-duty vehicles.

iii/ Promoted uptake of sustainable fuels in the aviation and maritime sectors complementing the ETS which makes polluting fuels more expensive for suppliers.

In this perspective, the ReFuelEU aviation regulation will oblige fuel suppliers to blend an increasingly high level of sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) into existing jet fuel uploaded at EU airports with a targeted percentage of 63% by 2050 (see table below). The generic SAF term refers to a broad range of liquid drop-in fuels substitutable to conventional aviation fuels, including advanced biofuels and synthetic fuels produced from green electricity. The latter type of fuel notably includes e-kerosene (also known as synthetic kerosene) which is generated by combining low-carbon hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Noteworthy is the EC taking a restrictive approach to low-carbon hydrogen and only considering use of green hydrogen to produce such type of synthetic fuel (see below).

Table 3. ReFuelEU: overview of proposed milestones for increased supply of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF)

Source: European Commission

In parallel, through the upcoming zero emission aviation alliance, the EU will support disruptive aircraft configurations using electric batteries or fuel cells.

On its end, the FuelEU Maritime proposal to promote sustainable maritime fuels will create new requirements for ships, regardless of their flag, arriving to or departing from EU ports, by imposing a maximum limit of GHG content of the energy they use and making these limits more stringent over time, with a 75% GHG content reduction set for 2050, as shown in the table below.

Table 4. FuelEU Maritime initiative: overview of proposed milestones for the reduced GHG content of the energy used in shipping

Source: European Commission

Interestingly, in the field of maritime transport where decarbonisation options are fairly limited for the time being, EC’s proposal accommodates all renewable and low-carbon fuels, such as liquid biofuels, e-liquid, decarbonised gas (including bio-LNG[3] and e-gas).

To tackle the climate footprint of the energy sector which accounts for 75% of EU’s GHG emissions[4], EC’s proposed approach relies on three distinct pillars with targeted impact on the electricity generation, building and mobility sectors:

i/ Revised renewable energies development targets. EC’s package calls on an accelerated development of renewable energies. To this end, the updated Renewable Energy Directive (RED) proposes to increase the overall binding target from the current 32% to a new level of 40% in the EU energy mix by 2030. Such overall objective will be complemented at Member States’ level by country-specific measures for what concerns the use of renewable energies across the industry and mobility sectors, in particular through the uptake of renewable fuels such as low-carbon hydrogen;

ii/ Revised energy efficiency targets. The revision of the Energy Efficiency Directive proposes to increase the level of ambition of the energy efficiency targets at EU level and to make them binding. This should lead to a 9% reduction in energy consumption by 2030, compared to the baseline projections in 2020. To this end, the EC is currently working on a revised version of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive due later in the year. In addition, as part of the Effort Sharing Regulation (see above), Member States will be required to achieve new savings of final energy consumption of at least 1.5% each year from 2024 to 2030, up from currently 0.8%;

iii/ Revised taxation structure for various energy vectors/fuels incentivising use of the cleanest sources. Through the revision of the Energy Taxation Directive (ETD), EC’s package proposes to align the minimum tax rates for heating and transport with EU climate and environmental objectives (see table below).

To this end, EC’s proposed scheme introduces a new structure of tax rates based on the energy content and environmental performance of the fuels and electricity, while broadening the taxable base by including more products in the scope and by removing some of the current exemptions and reductions benefiting fossil fuels. In particular, kerosene used as fuel in the aviation industry and heavy oil used in the maritime industry will no longer be fully exempt from energy taxation for intra-EU voyages in the EU.

[3] Bio-LNG is a form of liquefied biomethane. As mentioned above, use of biomethane in mobility or power generation offers clear albeit indirect climate benefits given it does emit CO2 upon combustion in the same proportion as that of natural gas.

[4] Through use of fossil fuels to produce electricity or to satisfy final energy demand in the buildings, industry and mobility sectors.

Table 5. Overview of the proposed rates under the Revised EU Energy Taxation

Source: European Commission

The Fit for 55 also proposes some “safety nets” to accompany the potential social impact of the accelerated energy transition

As mentioned above, one of the key pillars of EC’s proposed package is the introduction of various policy instruments to accompany the potential social impact of the targeted accelerated energy transition in the buildings and transport sectors.

The main instrument underpinning such objective is the proposed setting of the so-call Social Climate Fund. This fund will “support EU citizens most affected or at risk of energy poverty” as a result of the targeted disruptions in the supply of fuels in the buildings and transport sectors. The EC expects it to provide €72.2bn over seven years in funding for renovation of buildings, access to zero and low emission mobility, or even income support.

While it provides for the removal of a series of national exemptions and rate reductions for the use of fossil fuels (see above), the Fit for 55 package also includes the possibility for Members States to exempt vulnerable and energy poor households from taxation on the supply of heating fuels and electricity. According to the EC, this targeted exemption will help support and protect vulnerable households during the transition to cleaner energy sources.

***

Interestingly, EC's unveiling of its decarbonisation toolkit for the EU comes just a few weeks after the International Energy Agency (IEA) released a widely-discussed energy scenario underpinning the achievement of a 1.5 °C scenario by the world economy in line with the most ambitious climate change mitigation target set under the 2015 Paris Agreement[5], the Net Zero Emissions scenario (NZE).

As we commented in an ad hoc report (see IEA’s NZE scenario: is this the moment of truth for the energy sector?), IEA's NZE scenario positions itself as the most ambitious and comprehensive toolkit devised to date in the perspective of global climate change mitigation. For these reasons, it offers a valuable benchmark against which to assess the various disruptions and policy options underlying EC's Fit for 55 package.

If we compare the latter with IEA’s NZE, we notice obvious similarities in the overall decarbonisation pathways underlying both approaches, as reflected by:

i/ The central target of removing use of fossil fuels to the largest possible extent in buildings, industry and mobility, in particular in the latter two sectors given their reliance on fossil fuels either as a feedstock and/or as a fuel (see above). In both approaches, a mix primarily consisting of low-carbon electricity and low-carbon hydrogen is set to replace fossil fuels (oil, coal and natural gas) in most of their present-day uses.

In this perspective, EC’s overall approach focuses heavily on the development of renewable energy to support the “decarbonisation by electrification” approach in transport and buildings but also to support the development of green hydrogen (solar/wind energy-powered electrolysis) to complement low-carbon electricity, in particular through the uptake of low-carbon fuels in the transport sector.

In its modelling, the IEA sees a fully carbon-free electricity sector covering nearly two-thirds of final energy demand by 2050[6], with low-carbon fuels (including low-carbon hydrogen) covering the bulk of residual demand by then (20%);

ii/ The pivotal role of carbon pricing in incentivizing, through appropriate price signals, technology disruptions as well as climate-friendly behavioral changes across societies. Although the EC does not draw any specific carbon price scenario in its package, it is clear that the proposed tightening/enlargement of the ETS aims to make carbon allowances increasingly scarce and expensive for the various sectors covered. The widely accepted view among ETS observers and practitioners is that for EU carbon allowances, the proposed measures are likely to fuel an upward price move to levels close to €90-€100/ton CO2 by 2030 (vs. €50-€55/ton CO2 currently – see chart below).

On this front, we note IEA’s NZE relies on a thorough implementation of carbon pricing mechanisms across the globe, with particularly aggressive pricing modelled in developed economies ($75/ton CO2 in 2025 moving up to $250/ton CO2 by 2050).

[5] The Paris agreement sets the objectives of “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2° Celsius above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5° Celsius above pre-industrial levels”. Such targets entail reaching carbon emissions neutrality around 2050 followed by negative emissions thereafter.

[6] 90% of the electricity would be produced from renewable sources and 10% from nuclear sources by then.

Figure 2. EU ETS: trend in carbon allowance price (€/t) since 2017

Source: Bloomberg

iii/ Both the EC and the IEA stressing the evolutions / disruptions necessary at the technological and behavioral level to promote the widest possible exit from fossil fuels in the different sectors of the economy as well as a responsible use of energy and natural resources by individuals in their daily lives: development of reliable and cost-effective zero-emissions vehicles and devices, behavioral changes affecting direct use of energy (energy efficiency) and transportation means. EC’s revised taxation scheme for fuels / energy vectors precisely aims to incentivize such behavioral changes, in particular in the mobility sector;

iv/ The importance of accompanying the social implications of the abovementioned necessary disruptions in the energy sector, while it is fair to say that EC's package focuses more heavily on affordability issues than IEA's NZE. Such difference can easily be accounted for: IEA's NZE has a global perspective and therefore looks into developed as well as developing regions. For the latter, due to lack of infrastructure, access to energy still takes precedence over all other affordability considerations. In addition; EC's social awareness is very clearly motivated by the lessons drawn from the recent "yellow vests" crisis in France and the need to prevent any confusion between the purpose of environmental taxation and the government's use of associated tax revenues.

A cross-reading of EC's Fit for 55 package and of IEA's NZE also highlights a number of divergences between the two decarbonisation approaches, as well as some apparent inconsistencies in EC’s proposal.

EC’s focus is mainly on buildings and mobility… for now

In general, EC's Fit for 55 package focuses more heavily on the decarbonisation of the transport and mobility sectors than on that of the industry sector, whilst IEA’s NZE takes a more holistic approach, with heavy emphasis on the decarbonisation of industry alongside other hard-to-abate sectors.

For the time being, EC’s proposals for the industry sector’s decarbonisation (in particular for what concern such highly CO2 emissive and energy-intensive activities as production of cement, steel, chemicals, etc.) mainly revolve around the proposed strengthening of the ETS. For these activities, such strengthening will come through the tightening of the rules governing the allocation of free allowances under the carbon leakage mechanism. In practice, a certain number of key parameters surrounding this mechanism are set to evolve. In particular, the EC mules revising emissions benchmarks as from 2026 for each of the activities concerned (see above), which may have a strong impact on the volume of additional allowances that the installations concerned will have to purchase and, ultimately, on the decarbonisation pace that they will have to embark on within the framework of the ETS.

In EC’s approach, electricity (from renewable energies) is the queen mother of decarbonisation

Besides, in the current scope of sectors/activities covered, EC’s package reflect a more restrictive approach to the various vectors/low-carbon fuels supporting the economy’s decarbonisation than the one underlying IEA’s NZE.

Unlike the IEA which views development of nuclear energy as a necessary complement to renewable sources to support the ‘’decarbonisation by electrification’’ approach, EC’s package does not address nuclear power’s potential contribution to meet incremental demand for low-carbon electricity. Such stance comes as no surprise given the lack of consensus at EU level around the potential role of nuclear in the energy transition and the continuing debate on the classification of this activity in the Green Taxonomy. That being said, the potential inclusion of indirect (scope 2) emissions in the CBAM from 2026 onwards (see above) could provide indirect support to the use of nuclear power in the EU in energy intensive industrial activities such as steel, cement and above all aluminum production.

Besides, in its proposed new emissions standards for cars and vans, EC’s sole focus on direct emissions results in a severe narrowing of the available technology options by 2035. By then, we understand BEVs and FCEVs would be the sole technologies compliant with the proposed standards. This means the use of biomethane to fuel light-duty vehicles would be excluded regardless of the technology’s lifecycle due to biomethane’s indirect climate benefits (see above). In addition, in the revised ETD, electricity would be the least taxed fuel/energy vector alongside green hydrogen, regardless of the underlying generation process. Both measures can be accounted for by EC’s intention to massify final uses of electricity in light-duty mobility and buildings heating, this to generate economies of scale in equipment manufacturing and ultimately achieve substantial cost reductions along the value chain benefiting final users.

What role for CCUS?

Interestingly, EC’s restrictive approach to low-carbon electricity is also noticeable when it comes to the potential production and uses of low-carbon hydrogen. Whilst the IEA discriminates between carbon-intensive hydrogen (grey H2) and low-carbon hydrogen (blue and green H2[7]), the EC draws a distinction between hydrogen from renewable sources and hydrogen from fossil fuel sources. The latter’s contribution is disregarded in particular for the uptake of sustainable aviation fuels regardless of whether direct CO2 emissions from steam methane reforming are mitigated using carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS) processes. EC’s approach to renewable hydrogen means the contribution nuclear powered electrolysers would also be disregarded.

When it come to the production of hydrogen through steam methane reforming, EC’s distinction implicitly ignores the use of potential CCUS to produce the abovementioned "blue" form of low-carbon hydrogen. In view of the importance of pending subjects in the industrial sector, it is probably too early to draw final conclusions on EC’s perception of the potential role of CCUS in such activities as refining, steel and cement production. Resolution of such pending issue will therefore have to be monitored alongside the conclusion of EC’s ongoing review of the carbon leakage mechanism (see above). In practical terms, in the cement industry, there is basically no alternative to CCS to tackle direct emissions from the production process itself[8]. In this perspective, a supportive element in EC’s package is worth mentioning, taking the form of a change of accounting standards in the ETS: in its package, the EC proposes that allowances should not be surrendered for emissions permanently stored which de facto incentivizes uses of CCUS in activities subject to the ETS.

By contrast, we note EC’s roadmap to plant three billion trees by 2030 with a view to achieve net carbon removals of 310 Mt of CO2 equivalent in the EU by 2030, an increase of about 15% compared to today. This would suggest the preferred use of nature-based solutions over technology-based removal processes such as CCUS. As mentioned above, the exact status of CCUS in EU’s decarbonisation is likely to be clarified with the planned overhaul of the carbon leakage mechanism.

These uncertainties surrounding the status of CCS are worth stressing in light of the important role such process has in IEA’s NZE for the achievement of global carbon neutrality by 2050. The IEA indeed expects CCUS to be central in removing the bulk (5.25Gt) of the carbon dioxide the world economy will continue to emit by then (7.6Gt) due to its persisting reliance on fossil fuels in some sectors such as industry and power generation (though mostly in developing countries), the remaining emissions (2Gt) being deal with through alternative carbon removal processes (direct air carbon capture – DACC - and bioenergy using carbon capture and storage).

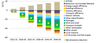

Figure 3. Average annual CO2 reductions from 2020 in the NZE

Source: IEA (2021)

[7] Produced through water electrolysis powered by low-carbon sources of electricity (renewable and nuclear energies), green hydrogen is obtained using a climate-neutral production process. This is in stark contrast to so-called grey hydrogen obtained using steam methane reforming (SMR), a process that remains dominant in the world (accounting for 95% of hydrogen production). While this process is carbon intensive (global median intensity of 9kg CO2 per 1kg of H2), its carbon footprint can be neutralised by fitting the steam cracker unit with a carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS) system. This produces what is referred to as blue hydrogen. See the general study published in December 2020 by Natixis on the hydrogen sector, which contains a presentation of grey, blue and green hydrogen production, “Low-carbon hydrogen: sensing the path to large-scale deployment”.

[8] As the IEA stresses in an ad hoc report on CCS (see https://www.iea.org/reports/ccus-in-clean-energy-transitions), the cement industry “generates significant process emissions, as it involves heating limestone (calcium carbonate) to break itdown into calcium oxide and CO2. These process emissions – which are not associated with fossil fuel use – account for around two-thirds of the 2.4Gt of emissions from global cement production and more than 4% of all energy sector emissions. With no demonstrated alternative way of producing cement, capturing and permanently storing these CO2 emissions is effectively the only option”.