Climate worst performers under strain from ECB's Green QE, collateral and parliamentary proposals for capital rules changes

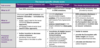

Details were released late September on how ECB’s green QE would work. The titling of bonds purchasing program focuses on climate change mitigation and began to apply to corporate bonds on October 1st, 2022. The ECB disclosed the criteria it henceforth uses to assess companies’ climate performances and upon which its lopsided bonds purchasing is built. Latest announcements reflect a turning point because extensively debated policy and regulatory changes are finally coming to life, or are on the verge of being enacted (see the figure 1 below).

In Europe, this pressure on “brownish companies” is occurring or envisioned (legislative proposals) through multiple channels:

i Green QE for non-financial corporates bond issuances with poor climate performances (some issuers are to be partially shunned in the ECB’s outright purchase policy), effective since October 1st 2022

ii Collateral rules adjustments for banks refinancing from the ECB (haircuts applied to “brown corporate bonds” used as collateral), with a progressive entry into force on October 2022 and a full implementation before the end of 2024and

iii Proposed MP amendements on rudential adjustments touching upon Solvency II pilar 1 provisions. They would introduce higher capital requirements (“overweights”) for lending to fossil-fuel related companies. These provisions are still under negociations at the Parliament level.

The aim of these green tilted policies is to incentivize private sector decarbonization, including through their banking funding, while handling climate transition risks. Such adjustments or twists will likely end up deteriorating the funding access of “brownish companies”. If ill-designed, the criteria and mechanisms will not necessarily spur and award transition efforts of companies (see our Series “Brown industries: the transition tightrope). The main question legislators must ask is whether the criteria will allow to discriminate companies exposed to fossil fuels among each others, i.e. differentiate transition “laggards” or “deniers” from “early movers” and “foreruners”, and create the right incentives. The criteria must allow a minimum granularity and reward or even spur strategic moves and decisions. In that case, within brown sectors, there would be companies harshly affected, while the best performers would even see their funding access improving (dispersion effect).

The criteria used to define “poor climate performers” vary across policy uses and intents. They are defined either through levels of carbon emissions, existence of forward-looking targets, quality of disclosure, exposure to fossil fuels (with a strong nuance made on “expansion” and “exploration”), or existence of transition plans. Transparency and criteria harmonization by the different EU monetary or supervisory authorities would be highly welcomed.

To make such radical policy changes acceptable, less abrupt, and not perceived as a synonym of exclusion, “grace periods” and derogatory criteria are granted to highly emitting companies and/or their financiers. However, such exemptions are all built on the notion of “transition plan”, which suffers definitional and verification shortcomings. There is indeed a lack of commonly agreed and robust definition, which poses a risk of confusion amongst external auditors, who may interpret differently these derogatory criteria.

1. Green Quantitative Easing (QE): new details on the climate scoring methodology

Pursuant to the announcement of the greening of its corporate debt portfolio and collateral framework (see our August 2022 analysis here), the ECB published on September 19 further details on its methodology to tilt the Eurosystem’s corporate bond purchasing as of October 2022[1], as per its climate action plan released back in July 2021[2].

Details on methodological aspects to assess corporate issuers have been clarified. Each company will be assigned a climate score resulting from 3 components (details below, Figure 2):

- its backward-looking emissions (retrospective score),

- its forward-looking targets (prospective score) and

- the quality of its reporting (climate disclosure).

Criteria analysis

Looking at past emissions, the evaluation of performance will be both best in universe (for scope 1 and 2 emissions) and best in class (for scope 3 emissions), thus penalizing highly emissive sectors although in unknown proportions. Ponderation between sub-scores is not disclosed either.

Somehow surprisingly, there is no reference to the EU Taxonomy criteria and ratios which could as of 2023 be used as alignment data. Furthermore, details on disclosure criteria assessment are lacking; we ignore how their completeness and accuracy will be assessed as well as what is a relevant “third-party” for their review (that would count as a sign of quality).

The individual scores are intended to be used by the ECB to adjust its primary bids in favor of better performances, but also in imposing maturity limit (the maturity cap number of years is also unknown) for bonds issued by companies with lower climate-scores. Specific numbers or orders of magnitude are unknown and might remain so as the ECB does not intend to fully disclose its calculation rules, nor issuers’ individual scores.

Issuer specific score will not be published but market participants and data providers will try to figure out what the scores might be. Natixis Green Weighting Factor methodology for general corporate purpose financing is built upon Carbon4’s model, whose criteria are overlapping with ECB’s sub scores and who is one of the official carbon data providers of the Eurosystem, and thus might provide us with a fair idea of the used assessment, though to be noted that only reported data will be considered when it comes to emissions intensity...

Regarding the GSSS Bonds market, the ECB allegedly seeks to incentivize the issuance of green bonds through a favorable treatment, in particular those compatible with the (still under negotiation) European Green Bond Standard (see our latest article on the EU-GBS here). However, the ECB will do so while “aggregate purchases of each issuer will continue to follow the tilted benchmark”. Such preferential treatment could therefore possibly be at the expense of one’s vanilla debt and widen the spread between green and straight debt. Meanwhile, there is no mention of a specific treatment or factoring for sustainability-linked bonds with climate-KPI[3].

Foreseeable effects

Overall, the criteria for the climate score announced by the ECB should incentivize a wide range of issuers and sectors to improve their climate risk profile and performance – until their climate score improves.

This green QE is explicitly penalizing worst climate performers, though tilting magnitude is ignored. It does constitute an important incentive to improve climate performance and transparency, to hedge against rising interest rates and the end of accommodative monetary policies. The existing disclosure gaps must be shortly filled by issuers if they do not want to be penalized (only reported data is accounted for the 2 first sub-scores).

However, net effects remain hardly predictable from a real economy decarbonization standpoint. On the one hand, the actions remain limited to the reinvestment of repayments (corporate debts in ECB portfolios approaching maturity representing around 30bn dollars per year) [4]. On the other hand, the green QE excludes financial institutions groups (FIG) and public sector (SSA) from the scope for the moment while they account for ~79% of the ECB’s Asset Purchase Program (APP) [5]. Extension to other types of issuers however is not excluded but will depend on data availability, that is supposed to increase with the upcoming adoption of the CSRD – yet unfit for this very purpose[6].

2. Collateral framework for banks refinancing: unknown criteria and haircuts calibration on brownish counterparts

The ECB also announced in July 2022 that in the future it will consider climate change risks in its collateral framework and require compliance with the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)[7] where possible, though without specific guidance at this stage.

In addition to limiting the “share of assets issued by entities with high carbon footprint that can be pledged as collateral by counterparties when borrowing from the Eurosystem” (before end of 2024), it would especially take climate change risks into account in its assessment of haircuts on corporate bonds used as collateral as of October 2022.

The extent of the haircut applied remains however unknown and there is no indication of a premium for assets or counterparties considered as better performers. The methodology used to weight the haircut applied has not been disclosed (one could ask whether the issuer-specific climate-score used for assets purchasing will be used or not). Minimum consistency in climate scores at entity level for various purposes seems though highly necessary.

However, the Eurosystem has recently developed common minimum standards (data sources, methodology and processes) for integrating climate change risks into its internal credit rating systems (ICAS)[8] approved by the ECB earlier this year and set to enter into force by the end of 2024. As ICAS are one of the three sources of credit risk assessment within the Eurosystem collateral framework, these standards are a key step for better incorporating climate change risks into the ECB’s risk assessment. It is explained that these climate-related standards will follow the concept of “single materiality”[9], and that the analysis of climate risks will be carried out entity by entity (factoring probably transition risks, but also physical risks), first for large companies of highly emitting sectors, then for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) of the same sectors, and before other companies starting with the largest.

ICAS will rely on companies’ disclosure under the CSRD as the primary source for data on climate change risks as soon as they are available – i.e., 2025 for the first companies, which, compared to the timeline given to haircut’s review according to corporates’ climate-performances (applied as of this month) raises the question of information availability. We ignore what data will be used in the interim, but the Eurosystem encourages companies to obtain firm-level data from other sources in the meantime (such as disclosures under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive[10] or the EU Emissions Trading System[11]). Finally, where no firm-level information is obtainable, one should use sectoral or regional proxies.

3. Proposed prudential penalizing factors for fossil fuel companies

While both regulators and civil society attempt to understand where the financial sector stands in terms of financing the fossil fuels industry[12], credit exposures to fossil fuel assets of the 60 largest global banks have been estimated to 1.35 trillion dollars by some NGOs[13]. The debate – and controversies- over the need and relevance of both a brown penalizing factor and a green supporting factor has been unfolding for many years already. Today, the integration of climate-related risks remains on top of financial supervisors’ agenda[14] and may enter the European banking regulation[15]. Indeed, in the context of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR3) revision, four amendments[16] have been proposed by some EU Members of Parliament on Pillar 1[17] to introduce a capital overweight (increased risk factor, i.e. higher capital requirements) for counterparties exposed to fossil fuels.

The amendments distinguish two categories of assets, further penalizing those corresponding to “new capabilities”, i.e. investments resulting in the increase of the fossil fuel exploration capacity post January 1st, 2022, with a factor of 1,250%, compared to a factor of 150% for assets exposed “only” to existing fossil fuel resources. This breakdown is inspired from IEA’s findings as part of their Net Zero Emission scenario. It reads as follow in the amendment : “companies active in fossil fuel sectors, which invest in expansion or exploration and plan to add fossil fuel resources to their production portfolio”.

Furthermore, there is another suggested amendement stating an overall limit that “An institution’s total exposure to existing and new fossil resources must not be higher than 10% of the institution’s Tier 1 capital at all times”.

All business lines in the energy value chain are affected by the amendments, including transport, refining, liquefaction terminals, trading, etc. If incorporated, this would complement the current method based on risk factors loss and damage and probability of default, and probably massively increase risk-weighting asset (RWA) and capital provisions requirements.

The proposed text however includes an exemption clause for companies who have adopted a “transition plan” with a trajectory compatible with the Paris Agreement, consistent with the disclosure provisions of the currently revised Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (including through provisioned assurance engagement on disclosures by a third party).

These amendments remain mere proposals at this stage. In all cases, they will most certainly revive the debate in the coming weeks on the adoption of such Pilar 1 provisions in the framework of the revised regulation and directive, expected to enter into force in 2025.

While this type of provisions may remain controversial, there is less and less doubt that climate change is now seen as a systemic risk to be taken into account including by regulators and prudential regulations.

More sophistication, granularity and usability, or simply definition, of the considered criteria proposed in these amendments’ provisions is highly needed and could make them both more acceptable, realistic, and efficient from a climate point of view. Beyond ponderation levels (1,250% is excessive), many ways forwards could be considered, such as:

- Discriminating among the fossil fuels with different capital requirements applying to coal, oil, non-conventional, gas, in order to factor their respective emission factors;

- Refining fossil fuel exposure criteria by using ranges of share of revenues (e.g., below 30%, between 30% and 70%, above 70%), share of installed capacity for power generation companies, or share of fossil fuels in CAPEX (for instance below/above 30%);

- Adjusting the heightened capital ratios across business lines and value chains (upstream / downstream/trade);

- Identifying the circumstances where the existing/new fossil fuels criteria (expansion and exploration) is hardly applicable and/or insufficient (e.g., trade finance);

- Introducing a clear definition and more importantly criteria to assess the scientific robustness of a Transition Plan for the “exemption clause” as CSRD-aligned disclosure will not be enough for this very purpose,

- Factoring trends, in particular residual (e.g. less than 5% of revenues related to coal) and/or decreasing exposure (with 5 to 10 year phase-out plans requirements), in a way which allows to handle energy security concerns and workforce management

- Considering absolute scope 1 to 3 emissions criteria

- Factoring high and/or fast-growing percentage of sustainable activities as defined by the EU Taxonomy (exemption or softened capital overweight for companies displaying taxonomy-aligned capex share above 20%, 40%, etc.)

- Clarifying that higher capital requirements would only apply to new financings and not to outstanding ones (no retroactivity and recalculation, grandfathering clause).

In all cases, the objective to efficiently support the massive reorientation of financings for sustainability and to support the fight against climate change should prevail over the temptation to “punish” banks on their existing and past practices. In this regard, the financing of solutions and the introduction of a climate supporting factor may prove at least as important as the introduction of a brown penalizing factor supported by those Parliamentary amendments.

Conclusion

Altogether these monetary and prudential initiatives will implicitly penalize "brown" activities and/or entities (forcing the latter to go “amber” or “greener” under the EU Extended Taxonomy semantics, see our study on “Extended taxonomy: in betweenness and elitism softening”, available here) whether it is through a haircut or a loss of eligibility for ECB’s bond purchasing programs. The main challenge lies in defining worst and stagnating climate performances and making the exemption around “Paris Agreement compatible transition plan” meaningful and assessable. In the absence of a brown taxonomy defining significantly harmful activities, and guidance on the maximum share of such activities in companies’ total revenues or capital expenditure, drawing such line is challenging. One expects consistency in the counterparts’ assessment methodologies, scores and criteria used at the EU level.

Eventually, the ECB will require companies to comply with the provisions of the new CSRD to be eligible to their programs. Therefore, an immediate effort on the availability of data, its auditability, and the evaluation of commitments by third parties seems essential.

[2] Climate action plan announced in July 2021 [online].

[3] Since January 2021, SLB-linked bonds are eligible as central bank collateral and also for Eurosystem outright purchases for monetary policy purposes (APP and PEPP). See the ECB’s press release.

[4] An amount estimated at around 30 billion euros will be reinvested each year by the ECB taking into account this climate weighting. See the figures in our article.

[5]See the scheme in our article.

[6] Disclosure requirements are spread over from 2025 (FY 2025) to 2029 (FY 2028).

[9] The standards will only consider risks that are relevant and material to a company’s creditworthiness

[11] EU carbon market.

[14]ECB, Detailed roadmap of climate change-related actions, July 2021.

[15] ECB, The way towards banks’ good climate change risk management, September 22, 2022.

[18] The Pillar I Requirement is the regulatory minimum amount of Capital which banks must hold set out under the CRR and the Capital Requirement Directive (CRD).